Au Bon Legacy

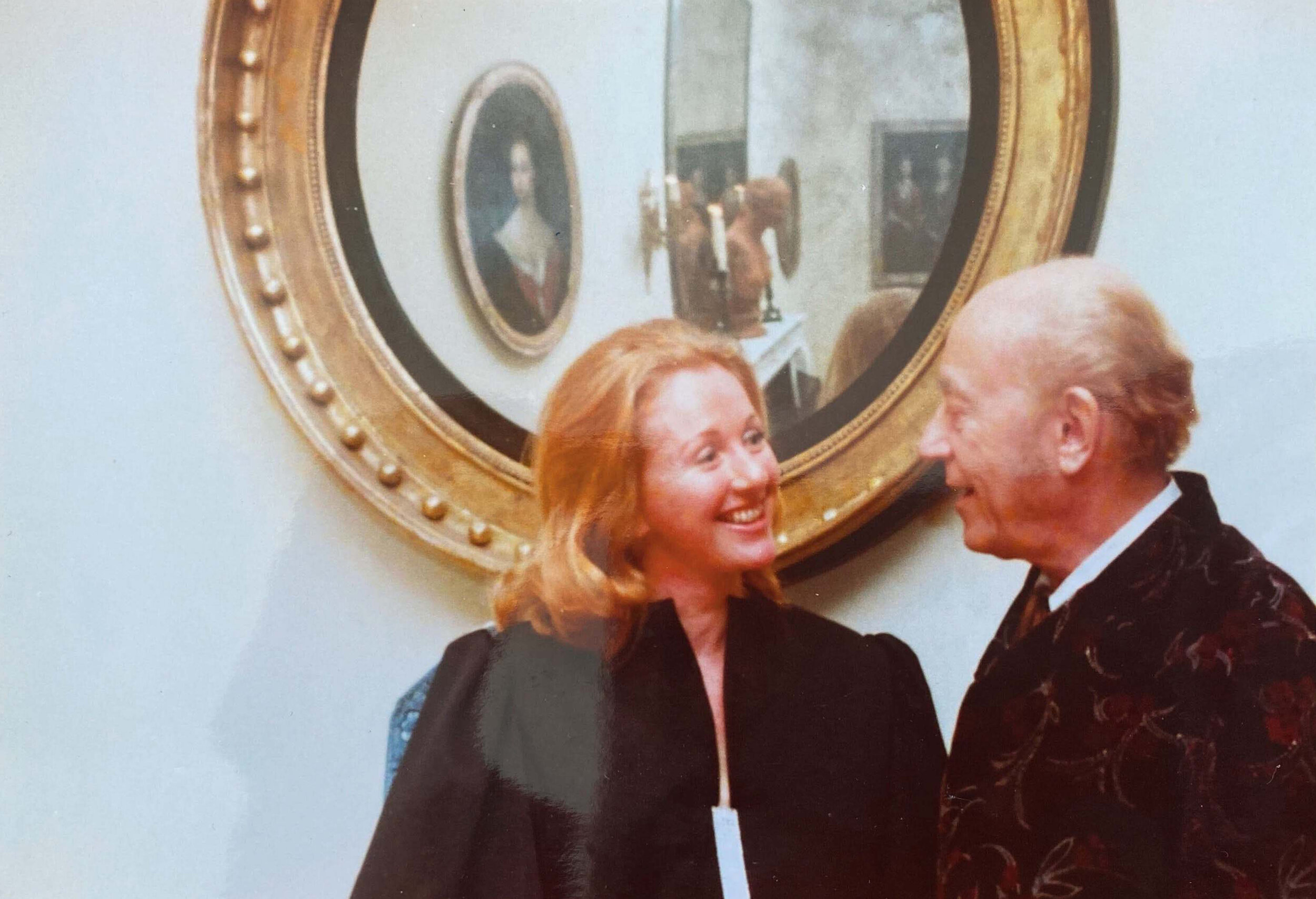

Co-authors Rajat Parr and Jordan Mackay remember long lunches and enduring friendships with Jim Clendenen

Co-authors Rajat Parr and Jordan Mackay remember long lunches and enduring friendships with Jim Clendenen

“The establishment of mutual respect, as well as a love of great wine and food, kicked off a two-decade-long friendship that would see us not only drink, eat, and taste together all over the US but also travel the world together.”

I had the great fortune to see Jim Clendenen only two days before he died. Laughing and joking as ever, he came over to my house with two other dear friends. While I had no idea that Jim was soon to physically depart this world, I was moved by the occasion. One of two great mentors in my wine career (Larry Stone, master sommelier and co-founder of Lingua Franca wines, is the other), Jim gave me my start in wine making and cooked many, many meals for me over our 20-year friendship. To reciprocate by cooking for him after a tour of the vineyard I now farm and a tasting of the wines I now make brought our relationship profoundly full circle.

I first met Jim in 2000, when I was wine director at the iconic San Francisco restaurant the Fifth Floor. At that time I had only two California Chardonnays on my list: Talley and Au Bon Climat, two of the few domestic wines I felt were truly balanced. When Jim came in, I knew exactly who he was. But he also made an impression. We shared a love of Burgundy, and as he perused my wine list, he tossed off erudite information with casual ease—the nuances of each Burgundian vintage, stories about various producers. I was blown away, thinking, “Wow, this is a guy I can learn from.” Some months later, at a gathering on the Central Coast, I had the chance to impress him in turn by successfully blind tasting a range of different wines.

The establishment of mutual respect, as well as a love of great wine and food, kicked off a two-decade-long friendship that would see us not only drink, eat, and taste together all over the US but also travel the world together, visiting domaines in Burgundy or the Rhône Valley, hitting beaches in Bali, and introducing him to my family in India.

Travel was an important theme; Jim showed me that if you are inspired by a wine and want to understand it, you need to meet the winemaker and see the vines. Only then can you translate that knowledge to your own endeavors. He went everywhere to learn firsthand about all of the (many) varieties he planted. I have done the same.

My most important travels were down to the Central Coast to see Jim, as he generously gave me my start in winemaking. At first he simply let me choose a couple of barrels of his wine, blend them, and put my name on it. (You have to start somewhere.) Later, he would teach me much about farming, fermenting, barrel aging, and more.

There was one totemic bottle that encapsulated our long history and that Jim eerily brought to lunch the last time I saw him—his 2006 Au Bon Climat Sanford & Benedict Chardonnay. That year, preharvest, we went to check the Chardonnay at Sanford & Benedict Vineyard. As we sampled grapes, he requested my thoughts on when to pick. It was the first time anyone had ever asked me that. It was early in the season, and no one else had picked yet, but the grapes tasted good to me. I said, “Jim, I think these are ready.”

So with no reason to trust my judgment, he told his crew chief, “Okay, let’s harvest 10 tons right now.” To balance these with some that were more ripe, he added, “We’ll pick the rest in another day or two.”

The catch was, as he would find out shortly thereafter, there were no more. Those 10 tons were it for that year. So the wine he made would be only around 11.5 percent alcohol (significantly lower than usual) with piercing acidity and sharp, lemony flavors. It was the kind of wine we both loved but a bit more racy and pointed than his typical style. That he brought that wine to our last meeting was odd but meaningful. In it lives the heart of our friendship, the essence of our shared vision.

A beautiful thing about being here is that Jim not only lives on in this bottle and every wine he made, his spirit also persists in the vineyards we see every day. In this I take comfort. He hasn’t left us at all. •

“Jim’s wines were flush with sun-kissed Santa Barbara County exuberance, but their moderate alcohols, restrained fruit, and absence of oakiness made them different from most other California wines of the time.”

My most poignant memories of Jim Clendenen center around lunch. It was midday when I drove down from San Francisco to the Au Bon Climat/Qupé winery to interview Jim.

The completely utilitarian winery was strange to me—there was not even a reception area. Inside was a cavernous open space, with high stacks of barrels stretching far into the distance. In part of the open space was a kitchen where I first saw Jim, phone tucked under his ear as he jabbered away at someone, while stirring pots and flipping pans with his hands. He nodded at me in acknowledgment but didn’t end his call. About 20 minutes later he was off the phone and placing large platters of food on the table as about a dozen bottles of wine appeared, some quite old and valuable. Ten or 11 employees materialized from back in the barrel stacks and took seats for lunch. Food was passed, wine was poured, and conversation began.

I was not the only outsider—a barrel broker from Oregon showed up, as did a writer from the East Coast and a wine shop owner from Atlanta. All the conversation swirled around Jim, as he opined on various topics, answered questions from the writers, and made wry jokes. Trying to keep up, I barely ate, furiously scribbling notes for my article. Eventually, people returned to work, and Jim and I continued talking.

I relate this scene because these lunches were a crucial expression of Jim. Lunch at ABC encapsulated the culture he created. He set a European-style custom of taking a break from work and enjoying a midday meal with wine and with coworkers and guests. The lunches were about tasting, yes, but also about camaraderie, bringing an intellectual cast to a nascent wine region that had risen from cattle ranches, barren hills, and broccoli fields.

Like his wines, Jim’s ABC lunches were classically European in spirit—humane, balanced, and based around food and wine in combination. Jim spent a lot of time in European wine regions and seemingly knew every important winemaker in Italy and France. Of course, the wines were flush with sun-kissed Santa Barbara County exuberance, but their moderate alcohols, restrained fruit, and absence of oakiness made them different from most other California wines of the time.

This difference was significant, because at that time a debate raged about California wine. The ripe, rich, and high-alcohol style was ascendant, encouraged by high scores from dominant critics such as Robert Parker. In pursuit of high scores, it seemed like every winemaker in the state made such wines and justified them with an ardent belief that this style was dictated not by critics but by California’s climate.

To those nonwinemakers among us, it was confusing. Ninety-nine percent of winemakers claimed wines had to be super ripe and high alcohol, yet they were contradicted by the existence of a scant few wines, Au Bon Climat chief among them, that were moderate in both categories and still tasted delicious.

The world must have seemed backward to Jim, as his became a lone voice in a wine world that knelt at the altar of ripeness (and Parker). Compounding Jim’s pain was a perceived betrayal. In the late 1980s Parker had championed Au Bon Climat, helping propel the brand to prominence. But apparently Parker’s tastes changed. As he dished out high scores to extremely ripe wines, the love he showed ABC disappeared. Years of receiving relatively moderate-to-low scores became the source of a lingering bitterness to Jim. Over the years, I often heard him rant about ripeness, scores, and Parker. “Of course, it’s possible to make balanced wines in California,” he would say. “I do it every year.”

In the end he was proved right. His wines found champions in the emergent sommelier community, which shared and amplified his thinking. Soon other winemakers became emboldened to flout the critics and join the growing movement of a “new” California paradigm of balance, energy, and moderation. And at the heart of this movement is the legacy that the stalwart, visionary Jim Clendenen created and perpetuated over lunch. •

See the story in our digital magazine

Illustration by Derek Charm

Crossroads

The high desert heats up with the reimagining of New Cuyama

The high desert heats up with the reimagining of NEW CUYAMA

Written by Katherine Stewart | Photographs by Dewey Nicks

Crossroads are fertile places for the imagination, where the best from a variety of distinct worlds collide with misfits from each. New Cuyama sits at the juncture of four of California’s most charismatic counties—San Luis Obispo, Kern, Santa Barbara, and Ventura—and from that unique and rather strange location, this high-desert hamlet seems to be in the process of mixing and matching new forms of California living. Even the landscape here has a bit of everything: dusty plains and grasslands, rolling hills and oak trees, all yielding to pines and mountain slopes in the shadows of the Sierra Madre.

Many of the loose ends at this unusual vortex in the Golden State gather around the bar at Cuyama Buckhorn.

Originally built in 1952, the Buckhorn has served as a roadside resort, piano bar, and community meeting point over the years. In 2018 Jeff Vance, the founder of a West Hollywood–based design-build firm, iDGroup, and Ferial Sadeghian, who is a partner in the firm, acquired the property and opened a new chapter in the New Cuyama story.

For Vance and Sadeghian, the Buckhorn represented a chance not just to combine their collective passions for architecture, restoration, hospitality, and great food but also to participate in a form of community building. Under their guidance, the 21-room property has been transformed into a place where low-key luxury meets midcentury aesthetics and cowboy cool.

Which is not to say that the Buckhorn Bar has lost touch with the old gang. On the wooden surfaces of the bar, you can trace the charred brands of local ranchers, and you can find some of those same ranchers enjoying a house-made margarita or a locally produced vintage. Among the regulars is Emery Johnston, a third-generation rancher whose great-grandfather arrived in the county by horse in the 1860s. It was Johnston’s grandfather who established the family ranch on the edge of the Los Padres National Forest in 1914; the rodeos that Johnston’s family hosted remain the stuff of legend.

Next to the entrance to the saloon, you’ll find a portrait of Johnston’s father, Lamar. Lamar was also known for having shot the nine bucks and one elk whose taxidermy mounts grace the walls of the bar. Over at the “Lamar Room,” as the hotel lobby is called, “Bob,” a stuffed brown bear that cowboys used to wrestle, stands like a watchman over the past.

Some of the cowboys here are renowned for their way with words. If you know anything about cowboy poetry, you probably already have heard of Johnston’s longtime friend Dick Gibford. A headliner at conventions such as the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko, Nevada, Gibford has a published collection and several anthologies to his credit. Making his home in a canyon that backs up to the forest, he spends most of his days on horseback surveying back-country springs and other water sources. Catch him in the right mood at the Buckhorn, and he just might tell you about the time he was jailed for alleged horse thieving. Or maybe he will recite an epic describing a night at the campfire with his horse and his philosophical musings about the rewards and costs of a life on the range.

In his poetry Gibford mixes inspiration from 19th-century poet Longfellow and 20th-century philosopher Krishnamurti with the realities of 21st-century life as a cowboy with a smartphone. This same blending of past and present seems to suffuse this town.

The story of Cuyama properly begins with the Yokuts and Chumash, the first settlers on this land. The name “Cuyama” comes from the Chumash word kuyam, meaning “clam” or “freshwater mollusk.” Today New Cuyama attracts artisans such as Carmen Sandoval, a jewelry designer and Chumash cultural educator who grew up on the Santa Ynez Chumash reservation. “When I’m in the zone with my creative work, I just tap into the spirit and into the ancestors,” she says, “and allow them to guide my hands and be my eyes.”

In 1843 the area changed forever when governor Manuel Micheltorena deeded 22,000 acres of land to what became Rancho Cuyama. As new ranches blossomed across the landscape, many of the prominent names of the era passed through here: Gaspar Oreña, Cesario Lataillade, José María Rojo.

“One of the things that makes this place so special is you have a cross section of people from all walks of life, every demographic you can imagine.” Ferial Sadeghian

Cuyama’s gilded age happened in the late 1940s. Prospectors struck oil, and the Richfield Oil Company (later ARCO) set up drills across the land. Productivity peaked in 1950, and ARCO built housing and facilities for its employees, planted trees, and put in an airfield. For a brief moment the town of New Cuyama, rich with black gold, was the pearl of eastern Santa Barbara County. But production dropped off over the ensuing decades, and the oilmen retreated.

In its heyday Cuyama’s semiresident celebrity was Johnny Cash. The singer had a home outside of Ojai, and rumor has it he downed a few more than he should have at the Buckhorn Bar.

The Buckhorn’s new owners have tapped in this vein of history in a wry way. On guest rooms’ bedside tables, where other hotels might place the Bible, visitors might find sociological studies of cowboy life or a book on Chumash ethnobotany. Or, best of all, Johnny Cash’s autobiography, Man in Black.

The Cuyama Buckhorn seems to be one of those rare spaces that exist as much for the locals as for guests. The key to the success of the place has been Vance and Sadeghian’s emphasis on investing in the community. The Buckhorn boasts a long list of partnerships with local businesses, from wineries and farmers to food producers and designers. Local products are featured throughout, from the offerings at the bar and restaurant to the minibar trays in the guest rooms.

Products from Cuyama Homegrown, a small-scale, environmentally sustainable family ranch led by Jean Gaillard and Meg Brown, are used throughout the property: Those include New Zealand spinach, leeks, heirloom beans, stone fruit, pickles, jams, and more.

Gaillard and Brown covered a lot of ground before settling in New Cuyama. He is from Belgium; she had pursued a master’s degree in agricultural economics; and the two lived for years in Europe and Africa before establishing their own farm in the valley. “This was not exactly my idea of retirement!” Brown says, laughing, as she shows off her apiary and henhouse bustling with chickens. A variety of water-saving innovations allows the farm to thrive even in drought conditions. “We don’t use herbicides, and we have to harvest some of our produce, such as sweet carrots, by hand. But we can provide top-quality products with a better taste,” Gaillard adds. “And the Buckhorn is incredibly supportive.”

The Buckhorn also works with Condor’s Hope ranch, an off-the-grid “dry farm,” which uses a traditional water-efficient technique for cultivating olive trees and wine grapes. Proprietors Steve Gliessman and Roberta “Robbie” Jaffe, both of whom spent their professional careers in agricultural and environmental studies, point out that dry farming forces grapevines to push their roots deep into the soil, producing a rich and concentrated flavor. “Our philosophy is to reconnect two of the most important parts of the food system: the people who grow the food and the people who eat the food,” says Gliessman. Jaffe adds, “We started Condor’s Hope Winery because we wanted to translate our philosophies about agricultural sustainability into action in real life.”

“Four men in cowboy hats engaged in earnest conversation over tri-tip sandwiches and pie; behind them, a pair of cannabis entrepreneurs in baseball caps discussed processing centers.”

Just a short stroll from the Buckhorn is the Blue Sky Center, founded in 2012 by the Zannon family, which owns the Santa Barbara Pistachio Company. Housed in the repurposed oil company headquarters, the center’s mission is to support resilience, inclusion, economic growth, and sustainability in the Cuyama Valley.

“They invested in this property to ensure that this large facility was in the hands of the community in perpetuity,” says Em Johnson, executive director of the Blue Sky Center. “They didn’t put together a plan of action for what Blue Sky was going to do. They creatively hired a whole young board of directors to come up with that. It was really a wonderful example of how a humble donor could transform nonprofits by just entrusting it to the younger generation.”

To assist food producers such as Cuyama Homegrown, Blue Sky offers assistance in navigating health and labeling requirements for products like jams and pickles. Blue Sky also works with the Cuyama Beverage Co., which makes a light bubbly mead; profits are reinvested in regenerative economic development in the Cuyama Valley. The center also supports Rock Front Ranch, which sells raw honey made from Cuyama Valley wildflowers, and Just Jujubes, whose founder, Alisha Taff, produces a dried superfruit also known as “Chinese dates.” Taff, a longtime horse trainer who is Chinese-American, notes the product’s high nutritional value—vitamin C, potassium, amino acids—and important role in traditional Chinese medicine. All these locally made products are for sale at the Buckhorn market.

Blue Sky has helped local ranchers develop horseback riding programs, and with the Desert Fellowship, it offers residencies for artists such as Noé Montes, whose photographs of the valley and its people adorn the center’s walls and those of the Buckhorn. Blue Sky also rents affordable space in the old airplane hangars to artisans like Garrett Gerstenberger of High Desert Print Company, which produces the graphic T-shirts worn by center staffers, and Alex Guerrero, who does highly specialized restoration work on “woodies,” or vintage wooden autos.

The 21-room property has been transformed into a place where low-key luxury meets midcentury aesthetics and cowboy cool.

Guerrero established his company, Warrior Wagons, after 18 years working for the late renowned restorer Doug Carr, and he rehabilitates vintage Rolls-Royces, Mercedes-Benzes, and Buicks to perfection. “Each car by itself can take five months to a year to restore,” he says. But Guerrero appreciates the sense of cohesion and support that organizations like the Blue Sky Center and the Cuyama Buckhorn have fostered. “I’ve never been in a place with such a community like this.” he says. “They are a blessing. Without them I wouldn’t have this shop.”

Some visitors to the Blue Sky Center end up staying awhile, to enjoy the five striking glamping trailers called “Shelton Huts,” designed by the Santa Barbara architect Jeff Shelton and his daughter, Mattie, which are maintained by the center and available through Airbnb and Hipcamp. And just like the locals, most of these visitors eventually find their way to the Buckhorn Bar, where you can encounter just about every lifestyle that California has to offer.

“One of the things that makes this place so special is you have a cross section of people from all walks of life, every demographic you can imagine,” Sadeghian says. Indeed, on a recent day at the Buckhorn, that cross section was evident. A bird-watching group twittered in a corner of the café. A tattooed woman with a T-shirt that read “Not Today, Colonizer” chased her toddler as she ordered coffee and pastries to go. Four men in cowboy hats engaged in earnest conversation over tri-tip sandwiches and pie; behind them, a pair of cannabis entrepreneurs in baseball caps discussed processing centers.

Meanwhile, a Tesla that screamed L.A. pulled up, and its driver unloaded a set of Vuitton luggage. Out by the pool, a couple in their sixties were engrossed in The New Yorker crossword puzzle, while a woman in a glittery bikini and cat’s-eye glasses lounged with her companion in the hot tub. In the evening local ranching couples on a date night sipped cocktails alongside an effervescent group of young bridesmaids who were here for a wedding. As dusk fell and the desert sky was illuminated with stars, guests, and locals congregated around the outdoor fire pits, chatting and laughing late into the evening. •

See the story in our digital magazine

Business + Pleasure

Architect Robin Donaldson’s mixed-use compound combines work and leisure in an urban setting

Architect Robin Donaldson’s mixed-use compound combines work and leisure in an urban setting

Written by L.D. Porter | Photographs by Michael Haber

I don’t think I could have designed a better situation,” says architect Robin Donaldson of his prepandemic decision to build a live/work compound—known as Anacapa Studios—in downtown Santa Barbara. Indeed, “when COVID came around,” he adds, “it almost looked like I was a genius.” The 12,000-square-foot site encompasses a trio of three-story buildings: the first two provide space for the local branch of his architectural firm, ShubinDonaldson; the third, at the back of the property, comprises Donaldson’s home and personal office. By design, only the first building is visible from the street; its tall windows often display the architect’s own artwork or architectural models.

“I wanted a seamless integration between my work and my life,” Donaldson says. “I wanted my family close to my office, and I felt I could blend the two better. So I have more family time.” His living quarters boast an expansive balcony with seamless views over downtown, and there’s even a solar-powered hot tub on the roof. “We’re not entirely off the grid, but close,” he notes.

Architects who design their own homes are often tempted to try things their clients might not (yet) accept designwise, and Donaldson is no exception. “I wanted to try some things,” he admits, “like leaving plywood floors. Some things are more finished, and some things are more raw and exposed in a way that I couldn’t do for a client.” He also wanted to prove that contemporary design could peacefully coexist with Santa Barbara’s mission-style architecture. “It’s not like I did something that’s wholly radical and dropped some kind of bomb on downtown,” says the architect. “It stitches into the neighborhood.” And the numerous benefits of urban living—with the beach, harbor, and restaurants all within walking distance—have been enthusiastically embraced by Donaldson’s wife, Eryn, and sons, Reed and Payne.

“One of the main of the main reasons I live here is because I love the ocean. I always have, since I was a kid,” Donaldson says. An Orange County native, he spent much of his childhood surfing and sailing in Santa Barbara at his family’s beach house. He stayed on for college, graduating from University of California Santa Barbara with a dual degree in architectural history and fine art. His decision to pursue architecture rather than art was prompted by a conversation with UCSB professor and renowned architectural historian David S. Gebhard, who informed the young Donaldson that “you can practice architecture in an artful way.”

At the time—the early 1980s—the most avant-garde architectural school in the United States was the Southern California Institute of Architecture in Los Angeles (SCI-Arc). After touring the premises, Donaldson was gobsmacked. “It was in this old warehouse. People were hanging from the rafters; it just looked like an artist’s studio, not an architecture school,” he says. “I thought this is where I’m going. And that was that.”

Donaldson was soon tapped to work for cutting-edge architecture firm Morphosis Architects— whose principal, Thom Mayne, would ultimately become an internationally known “starchitect”—and was appointed project architect for the Crawford residence, a Morphosis-designed home in Santa Barbara. Thereafter, in 1991, Donaldson established his namesake architecture firm with Russell Shubin. Now in its third decade, ShubinDonaldson has offices in Los Angeles and Orange County in addition to Santa Barbara.

The ethos of the Morphosis office and the teachings of Thom Mayne, notably the use of art to create imagery and forms to establish a unique language for architectural solutions, continue to inform Donaldson’s current practice. “[ShubinDonaldson's] buildings are the source of a lot of the forms and shapes that go into my artwork,” he notes. “There’s a cycle between what I call ‘artifact’—drawings, models, and so on—back to the next building, back to the next drawings, artifacts, back to the next building. It’s a virtuous loop to help push design ideas.” And the walls of his office and living space are filled with numerous examples. Recent pieces include large silk-screen prints that layer computer images of building details with splashes of eye-popping color, inspired in part by John Van Hamersveld’s iconic poster for The Endless Summer surfing documentary.

Currently Donaldson is focused on what could be the most important commission of his career, designing a home for Lynda.com founders Lynda Weinman and Bruce Heavin. The hilltop residence, composed entirely of concrete, will be embedded into the earth and covered with landscaping, an idea suggested by Heavin, an artist in his own right. “It’s a great collaboration between creative minds,” Donaldson says of the innovative structure that only 21st-century technology could produce.

In the meantime, Donaldson and his family are happily ensconced in their downtown compound, which he feels should be a model for the city’s future. “We’re pioneering a little bit,” he notes. “There aren’t a lot of residential projects that have been built within these few blocks. We need people living down here, a diverse population. We need the highly affordable. We need the ‘missing middle.’ We need all levels of diverse populations downtown. It’s perfect for it, it’s where the growth needs to occur.” ●

See the story in our digital magazine

Endless Summer

The fabled Miramar resort has had a colorful history — and not just because of its former blue roofs

The fabled Miramar resort has had a colorful history — and not just because of its former blue roofs

Written by Katherine Stewart | Photography by Dewey Nicks

Surfer, model, and actress Sanoe Lake hitching a ride to her room on the Miramar's pickup truck; the cast of surfers and models for a Roxy swim shoot take full advantage of the Miramar's pool during the mid-1990s.

A new series of Nicks' never-before-shown prints from this shoot and ’90s surf life debuted at the grand opening of the Montecito Mercantile at Montecito Country Mart. The show will run through September 15.

In the first decades of its existence, the Miramar resort was the kind of place that children imagine when they think about the way the world should be. “I assumed it would go on forever,” wrote Harold Keeney Doulton in his 1999 memoir, I Remember. Doulton, who was born in 1925, grew up in the Red Cottage, one of the first structures that his grandparents built—on a prime spot under two ancient oaks—after acquiring the oceanfront land in 1886.

Through the Roaring Twenties, the Miramar functioned as a health resort for the morning-after crowd. Montecito at the time was the kind of place where the loose nuts of a WASP world collected—the black sheep, the iconoclasts, the artists, and other refugees from East Coast civilization. Doulton’s childhood was a whirl of idyllic beach gatherings with the neighborhood children, punctuated by bonfires, fishing trips, idiosyncratic rituals, and some truly grand parties.

For Fourth of July celebrations, Max Fleischmann, son of the founder of the Fleischmann’s Yeast company, and Chris Holmes, his nephew, used to fund fireworks spectaculars at the hotel for Montecito residents and guests of the Miramar Beach. Chairs and benches were set out, and the pyrotechnics were shot off south toward Fernald Point. Doulton’s father hired two bagpipers and a drummer to march around the hotel grounds, paying them each five dollars and a bottle of Scotch to play songs like “Scotland the Brave” and “The Campbells Are Coming.”

“The Gilded Age resort morphed into a place for postwar exploration of the American Dream, California style.”

But the Great Depression brought an end to that first Miramar incarnation. Unable to keep the enterprise afloat, the Doulton family sold it to Paul Gawzner in 1939 for $60,000. The Gilded Age resort morphed into a place for postwar exploration of the American Dream, California style.

Gawzner transformed an old rail car into a coffee shop and painted the white rooftops of the buildings a striking blue. Mostly, he introduced a more relaxed and carefree feeling to the place.

Hillary Hauser, a photojournalist, undersea explorer, author, and environmental activist who cofounded Heal the Ocean, spent endless summers at the Miramar in the late 1950s, and remembers it as the scene of her first kiss. “I was maybe 14,” she remembers. “The ocean was wilder then. There was more kelp, there were sea anemones and tide pools. But for us kids there was the hamburger shack and the raft, which they anchored every summer. We would swim out there, talk, and hang out. And maybe have a kiss!”

For a certain crowd, Hauser recalls, gathering at this spot was a way of life, almost a religion, and it had a leader. “Hal Bates was our god, the center of our being,” she says, referring to a local radio jock who worked as a lifeguard at the beach. “We would have body surfing contests to see who would ride the waves the best,” she recalls. “And then there was a funny kid who showed up with a guitar he was always plinking. That was David Crosby, who ended up forming the rock band Crosby, Stills & Nash.”

“The Miramar drew masses of artists and writers and these wacky crazy eccentric trust-fund hippies”

For Ted Simmons, whose extended family owned the Miramar Beach Hotel and who was proprietor himself for several years, it was a place to grow up. “My first job after high school was working as a bellman. We wore these polyester blue coats. I worked under the legendary Grover Barnes, a true gentleman who passed away in his 90s after having worked at the property for over 40 years.” Tennis instructor Hilbert Lee was another Miramar fixture. “He was interested in people, and it didn’t matter who you were or where you were from,” says Simmons. “He’d be friends with Warren Buffett or the guy walking down the train tracks.”

Toward the end of its second life, the hotel had become a place with plenty of warmth and no pretensions. “The Miramar was run down, the bar was grungy,” says screenwriter and producer Tracey Jackson, daughter of Santa Barbara’s late society doyenne Beverley Jackson. “But the beach was as beautiful as ever, and that, along with all of its good vibes, was what the people came for.”

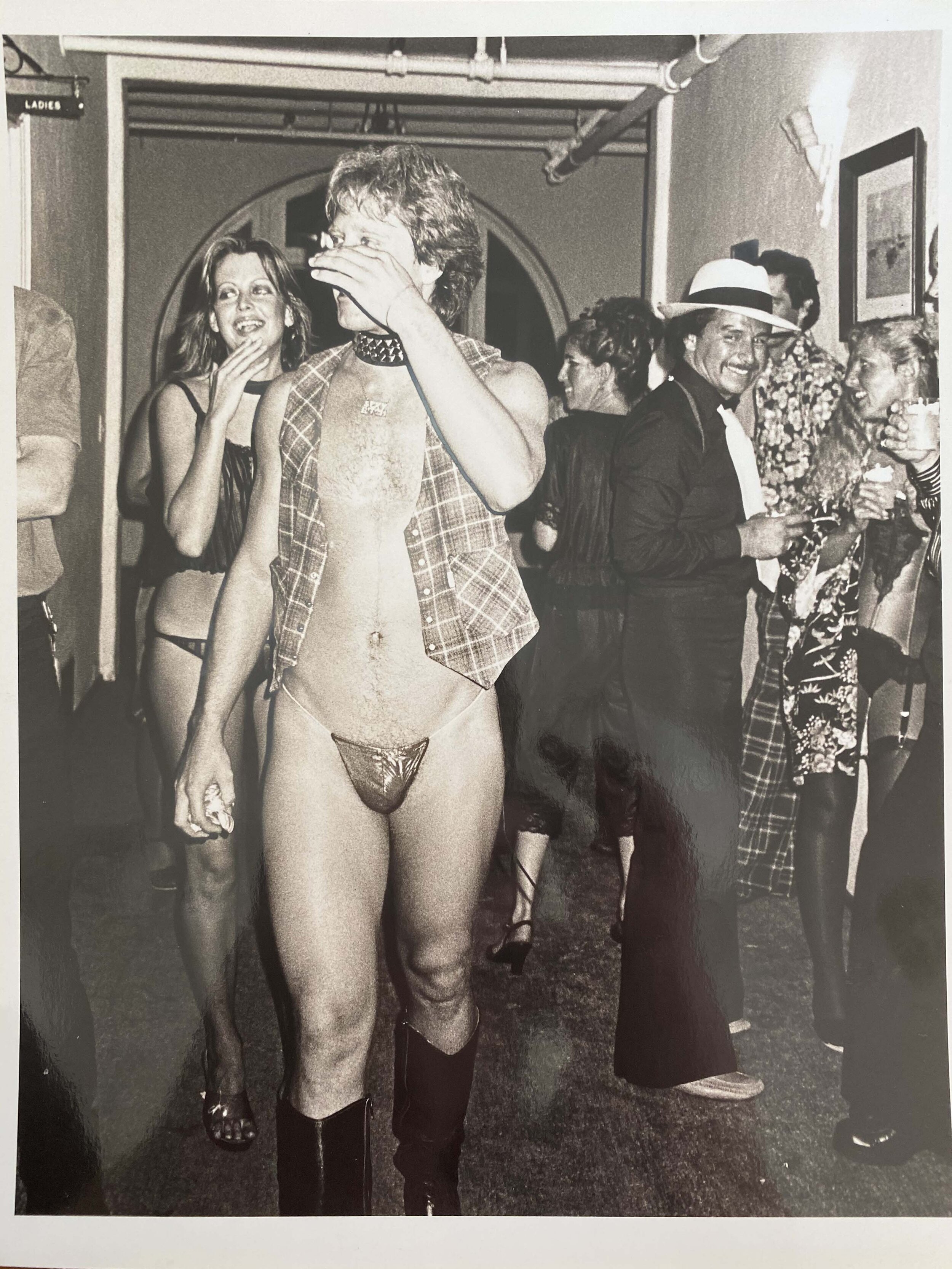

In fact, the artsy set loved it all the more. “The Miramar drew masses of artists and writers and these wacky crazy eccentric trust-fund hippies,” Jackson recalls. Many of these characters had discovered the place—and Santa Barbara—through the Santa Barbara Writers Conference, which Mary and Barnaby Conrad founded in 1973 and held every summer at the hotel.

“We put the Miramar on the map in the intellectual world,” says Mary Conrad from her home in Rincon, the site of the conference’s infamous opening- and closing-night parties. “We got Ray Bradbury, Dominick Dunne and Joan Didion, Charles Schulz, Gore Vidal along with his nemesis Bill Buckley, Neil Simon, Fannie Flagg, Alice Adams, James Michener, Eudora Welty, Artie Shaw—all the people of that era.”

Tommy's Miramar by Hank Pitcher. (From the book HANK PITCHER by Charles Donelan, courtesy Sullivan Goss Gallery.)

By the late 1990s everyone knew the hotel was due for a facelift. In a saga too well known to locals to belabor here, the ownership changed hands three times, and the old resort lay empty for nearly two decades.

Today, in its third era, the Rosewood Miramar Beach hotel, under the direction of Rick Caruso, is something new and strikingly opulent, from the graceful staircase in the Manor House, designed by the late Los Angeles architect Paul Revere Williams, to the well-appointed lobby, which evokes the ambience of a grand Montecito estate. The old train-car diner has been replaced with a festive aqua-colored drinks cart, shaped like a caboose, that serves the overflow from the Miramar Beach Bar. The old boardwalk, where children once rode their bicycles, now serves as a gathering spot for local glitterati.

But one feature remains the same. Two enormous old oak trees stand side by side in a grassy enclosure with a hammock strung between them. Most days you’ll see visiting children playing beneath the sturdy boughs, which are hung with lanterns that cast a warm glow as the sun fades.

Photographs; Skateboard and pool, Dewey Nicks; Writer’s conference, courtesy of Mary Conrad; Joan Didion, copyright Julian Wasser, Train-cars, Simmons, Barnes, Renon (5), Ted Simmons; Hauser, courtesy Hillary Hauser; Matchbox, Angel’s Antiques in Carpinteria

See the story in our digital magazine

Swept Away

Kenya Kinski-Jones shows the ocean some love as an ambassador for Project Zero’s climate mission

Kenya Kinski-Jones shows the ocean some love as an ambassador for Project Zero’s climate mission

Interview and Photographs by Kendall Conrad

I first met Kenya Kinski-Jones at a dinner and was instantly wowed by her beauty and, shortly thereafter, by her spirit. She is the daughter of music mogul Quincy Jones and model/actress Nastassja Kinski, and I wanted to photograph and interview her for my AFICIONADA series (kendallconraddesign.com), which profiles incredible women who inspire me. Kenya, 28, always dreamed of riding a horse on the beach—she loves the ocean—and we had a wonderful day shooting at Loon Point. She has recently joined Georgia May Jagger and Alexandra Richards, among others, to become an ambassador for the environmental nonprofit Project Zero (weareprojectzero.org)—a global network of scientists, marine activists, and cultural movers and shakers who are working to protect and restore our oceans. She’s been a very proactive and dedicated spokesperson, initiating ideas to promote and support Project Zero.

Please tell us about Project Zero.

Project Zero is a global mission to awaken the fight to protect and restore our ocean. It aims to establish a worldwide network of ocean sanctuaries, with the goal of protecting 30 percent of the ocean, within which it is prohibited to drill, mine, fish, or pollute—like national parks in the ocean. Relieving the climate emergency that we now face relies significantly on our ability to protect and support a healthy ocean, making Project Zero’s mission synonymous with a future that we can be proud of, a future that we and our fellow creatures on earth can survive and thrive in. I cannot think of a pursuit that is more urgent and crucial than this.

“Project Zero’s mission is synonymous with a future that we can be proud of, a future that we and our fellow creatures on earth can survive and thrive in. I cannot think of a pursuit that is more urgent and crucial than this.”

Why does the health of the ocean matter to you? The ocean is the largest ecosystem on earth. It works as an oxygen-creating and carbon-dioxide–absorbing powerhouse. The ocean is our planet’s biggest carbon sink. It is estimated that 93 percent of the earth's CO2 is stored or cycled through the ocean, which holds about 97 percent of earth’s water and supports a great abundance of life on the planet. Doing better by our ocean is one and the same as doing better by each other and ourselves. As Project Zero says: ‘No ocean, no us.’

What are some of your early childhood memories of being by the sea?

Being by the water, covered in sand and saltwater, are some of my most vivid recollections as a child. Today, while I marvel at the ocean’s beauty, strength, and magnificence, it is also sobering and humbling to stand before it. The ocean is vast, but it is also incredibly vulnerable.

What are some of your other passions and pursuits right now?

I’m interested in meeting creative people and collaborating. I am always learning. I write. I started modeling at a young age and have learned so much about myself since then. I love photography, fashion, and images. I am fortunate enough to have worked with [photographer and film director] Peter Lindbergh. I am a huge lover of animals and nature. I am committed to our planet and to the protection of our seas, land, and wildlife. I am always evolving, studying, and curious.

What’s your goal in life?

What stands out is that I want to make people feel less alone—and make them feel seen, heard, and understood in whatever way that I can. I want to make a small contribution to a much larger community. This will always be my underlying mission in whatever that I do.

Who or what inspires you?

The underdog, the underestimated, the survivor. People who have risen from deep pain, challenges, and tribulations in their life inspire me. The perseverance and gentleness—despite their pain—that people muster up when all odds are against them…that inspires me most.

What are your rules to live by?

Be kind, whether you’re interacting with someone you’ve known for years or a complete stranger. We never really know what someone is going through, what they have to return home to at the end of the day or whether they are barely getting through the day even though they put on a smile. I think it is vital to ask ourselves: What could this person be surviving today? This does not mean that one must become a martyr or forget one’s own personal boundaries. I’m just talking about an awareness that, as Zadie Smith has said, “Other people are as real as you are.” So I believe that whenever you come to that choice, whether that be in a mundane or monumental moment, be a light for someone.

“The ocean is so vast, it seems impossible that we could do anything to harm it. But today the ocean is in trouble. From overfishing to pollution to climate change—it’s as if we’ve declared war on the very ecosystem that keeps us alive. Our future and that of future generations depends on a healthy ocean. We can reverse the damage, but we must act now.”

See the story in our digital magazine

Relocating by Design

A family weaves their Danish threads into a new Santa Barbara fabric of life

A family weaves their Danish threads into a new Santa Barbara fabric of life

Maj Henriques creates a warm melange in her Montecito living room via furniture designed by her Copenhagen friends: a wall lamp and mint chaise longue by Muller Van Severen, and art by Studio Oliver Gustav. Around the hearth, a pair of chairs by Le Corbusier, a Linie Design rug, and a jolly yellow side table by E15.

Written by Olivia Joffrey | Photographs by Michael Haber

In my experience the Danes are a bit like Californians: laidback, warm in manner, open-minded, and generous. They are also dry in their humor and forthright in speech. This was precisely why I fell for the Henriques family, when I met them on Miramar Beach a year and a half ago. Maj Henriques, a classic Scandinavian beauty in the Greta Garbo mold, approached me wearing a long, striped caftan and said wryly, “So I hear you make scrunchies.”

“Home should be a personal collection of interesting things that make you happy and express your personality.”

I do not, in fact, make scrunchies. (Our daughters, classmates in school, had met earlier that week, and mine was wearing a patterned scrunchie someone had made her in some spare fabric from my own caftan line.) I laughed, and our friendship was cemented. That day Maj (pronounced “May”) and Frederik Henriques had only just landed in Santa Barbara. They, along with their two children, were recovering from jet lag by indulging in a sunset dip in the ocean.

Maj and Frederik are a Copenhagen powerhouse couple. He is an entrepreneur and a partner in Simple Feast, the wildly popular plant-based meal-delivery service that has taken Europe by storm since its inception in 2016. Three years later Frederik was tasked with expanding the company to the United States, starting in California’s Central Coast. (Their test kitchen is in downtown Santa Barbara, the main facility in Oxnard.) Maj herself is a renowned Danish entrepreneur. Her award-winning design agency, Creative Notes, made a name for itself with elegant, modern design solutions that attract clients in the fashion, furniture, hotel, and restaurant worlds. The agency’s output is so good that her work for clients often ends up in galleries, appreciated as fine art.

“Life is a sensory feast at the Henriques’ house. If the place could talk, it would be singing.”

Maj never expected to rebrand her family, but that is exactly what happened in 2019 when the Henriques packed up a fraction of their possessions and relocated from urban Copenhagen to beachside Santa Barbara. Maj’s experience as a designer became indispensable in the move. Just as she might help a client distill their brand into a moody mustard yellow or a slight undulation in a logo’s typeface, Maj packed up only the most potent bits of their Copenhagen life and transplanted them to California.

The Henriques’ Santa Barbara midcentury house, nestled in oak trees, is airy and high ceilinged, with sliding doors that invite the leafy surrounds in. Only a select group of furniture made the journey, and each piece carries some deeper meaning: There are chairs designed by a friend, photographs of a favorite coastal nook on the Oresund Belt, a quilt from a friend’s shop. While these threads of their Danish life speak to their roots, Maj underdecorated the house in pale sun-bleached colors, leaving it open to new discoveries and experiences. A year and a half after moving here, their shelves are now peppered with pottery from Ojai, art by California friends, trinkets from salvage yards, surf posters, and seashells. The result is overwhelmingly sunny and optimistic and decidedly unfussy despite its inherent design pedigree.

Magne and Frederik (and sister Hannah, not pictured) surf nearly every day. Before leaving for California, Magne held a coveted spot on the Danish national sailing team.

“The main thing,” explains Maj, “is that home should be a personal collection of interesting things that make you happy and express your personality.” Life is a sensory feast at the Henriques’ house. If the place could talk, it would be singing. There is a joy expressed in the surfboards leaning outside the back door, music and sunlight pouring through the rooms, the scent of eucalyptus gathered from a local hillside, a dining room table made in shop class by their son, fresh produce on the counter. The visual language in the home is succinct, but it celebrates change, beauty, adventure, and growth.

“It’s ok if things get scratched,” explains Maj. “You invited in the life. Let it leave its beauty mark.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

Through the Looking Glass

The magical world of ALOES in Wonderland

The super silvery leaf of Brahea nitida, native to the mountains of Oaxaca, Mexico.

The magical world of Aloes in Wonderland

Written by Thomas Cole | Photographs by Micheal Haber

Tucked into the eastern end of Santa Barbara’s Riviera lies Aloes in Wonderland, one of the more unusual horticultural destinations on the South Coast. The brainchild of Jeff Chemnick, this five-acre private botanic garden and nursery overflows with a mind-blowing array of exceptional plants. Blessed with a southeast-facing property in a unique microclimate and an entrepreneurial passion, he has built Aloes in Wonderland into one of our premier garden destinations.

“Our climate allows us to grow these otherworldly species.”

Chemnick’s excitement spills over as he leads you along twisting paths filled with masses of blooming aloes and stunning cycads. A much-appreciated stalwart of the Santa Barbara garden scene, Chemnick for years was known primarily as the cycad guy. “I was a horticultural one-trick pony,” he laughs, “though repeated botanical trips across the world opened my eyes to the sheer diversity of succulent or xerophytic plants. I saw a need and opportunity for these types of plants in Santa Barbara, so I began growing many of them.”

Pressed to explain this passion, Chemnick says that part of the plants’ appeal is based on radial symmetry. “Aloes, cycads, palms, and agave all share this basic architectural genetic code. That’s what makes them so beautiful. There’s something primal, almost a religious experience in what these plants evoke. I think we’re drawn to those patterns and these plants that don’t look like what’s next door. Our climate allows us to grow these otherworldly species. Aloes in Wonderland offers plants that are a departure from convention.”

“Aloes, cycads, palms, and agave all share this basic architectural genetic code. That’s what makes them so beautiful. There’s something primal, almost a religious experience in what these plants evoke.”

Chemnick confides that he feels the aloe is the quintessential plant genus for Santa Barbara—architectural, drought resistant, fire tolerant, and with a profusion of yearly flowers. With more than 600 different species, there are aloes to fit every garden size. “Everybody can create a garden. We might be limited by space and budget, but the imagination is boundless. Even the most modest garden can be a work of art with the right plants.”

Santa Barbara’s optimal growing conditions, abundance of unique plant material, and concentration of horticultural expertise allows us to push these plant boundaries in our gardens. Aloes in Wonderland provides the template. •

See the story in our digital magazine

Taste Maker

In her debut book, master gardener, home chef, and serial entertainer Valerie Rice shares her recipes for eating and drinking with the seasons

Valerie Rice at home in Santa Barbara, photographed by Dewey Nicks.

In her debut book, master gardener, home chef, and serial entertainer Valerie Rice shares her recipes for eating and drinking with the seasons

Text and images excerpted from Lush Life: Food & Drinks from the Garden (Prospect Park Books) by Valerie Rice, with a foreword by Suzanne Goin and photography by Gemma & Andrew Ingalls

I have been lucky enough to enjoy more than a few meals (and drinks and bottles of wine!) at Valerie Rice’s stunning Southern California paradise of a home, and I have to say that whoever came up with the title Lush Life has hit the nail directly on the head. But it’s not just the beautiful setting, the glorious garden, or the flavorful and captivating food and drink—the lushness stems right from Valerie’s heart and soul. Her passion for gardening, cooking, and entertaining is a triumvirate of riches to be enjoyed by anyone who finds themselves fortunate enough to be welcomed into her home. This passion and love for ingredients, where they come from, and the art of time around the table are Valerie’s magic, and she has captured that spirit and meticulously passed it along in this book. Suzanne Goin

“I may be late to parties and doctor’s appointments, but I’m always on time for what’s in season.”

Spring brings double joy to my garden: first, harvesting the new bounty of spring treasures, and second, digging in the dirt to start planting for the flavors of summer. After the somewhat sparse harvest baskets of winter, suddenly I’m faced with an overflow of lush, gorgeous produce: fava beans, sugar snap and sweet peas, breakfast radishes, brassicas, new potatoes, loads of lettuces, loquats, alpine strawberries, rhubarb, and citrus of all sorts fill our veggie beds and baskets. Everything, and I mean everything, is blossoming—from the roses first off the hook bloom to the pineapple guava trees—the thought of which makes me sneeze and smile all at the same time. In spring, preparing delicious meals just becomes a matter of how to best show off these natural goodies, and there are so many simple ways to incorporate all of the sweetness of this season. Valerie Rice •

Citrus Blossom Pisco Sour

2 oz (1/4 cup) Orange blossom simple syrup6 oz (3/4 cup) pisco2 oz (1/4 cup) fresh lime juice (from 3 limes)1/2 oz (1 tablespoon) egg whiteAngostura bittersFresh orange blossoms (garnish)

Directions: Fill a large cocktail shaker ¾ full with ice. Add ¼ cup orange blossom simple syrup, Pisco, lime juice, and egg white, and shake like the dickens. Strain contents into two rocks glasses. Add two drops of bitters on top of the foam. Garnish with orange blossoms.

Marinated Baby Artichokes with White Wine

2 large lemons10 to 12 baby artichokes1/3 cup extra-virgin olive oil6 fresh thyme sprigs4 garlic cloves, thinly sliced2 small Chile de Árbol2 Fresh bay leaves1 teaspoon diamond crystal kosher salt1/2 teaspoon freshly ground pepper2/3 cup dry white wine

Directions: Fill a large bowl with ice water; cut one lemon in half and squeeze it into the water. Using a vegetable peeler, remove the peel from the other lemon, cut the lemon in half; reserve the peel and halved lemon. Peel off the outer leaves of 1 artichoke in a downward motion (the leaves will snap off cleanly), until you reach a layer where the leaves are light green, almost yellow. Cut off ½ inch of the tip of the remaining artichoke top, which is pointy and sharp. Peel and trim the stem end, leaving about 1½ to 2 inches. Cut the artichoke lengthwise in half and place in the bowl of lemony water to prevent browning. Repeat with the remaining artichokes.

Drain the artichokes, then pat dry with a kitchen towel. Toss them with olive oil in a large bowl and place them cut side down in a large sauté pan (one with a fitted lid), adding any oil left behind in the bowl. Cook over medium-high heat until the artichokes begin to sizzle and turn golden brown, 7 to 8 minutes. Next, add thyme, garlic, chile, reserved lemon peel, bay leaves, salt, and pepper. Squeeze in the juice from the reserved lemon, and then add the wine and stir to incorporate. Partially cover and simmer until the tip of a sharp knife easily pierces the artichoke stems, 10 to 15 minutes, depending on the size of the artichokes.

See the story in our digital magazine

Flight Patterns

Sofia Richie + Donald Robertson Breeze Through Lotusland in Weekend Max Mara’s Latest Technicolor Capsule

Sofia Richie + Donald Robertson Breeze Through Lotusland in Weekend Max Mara’s Latest Technicolor Capsule

Written by Elizabeth Varnell | Photographs by Dewey Nicks | Produced by Creative Chaos/Gina Tolleson

Los Angeles native Sofia Richie is strolling through Lotusland across sprawling lawns, past succulents, and amid fern groves—just the sort of places frequented by dragonflies and other iridescent creatures of flight. “Santa Barbara has been my family’s escape ever since I was a child,” says the model and entrepreneur, who has combined this trip with a photo shoot for Weekend Max Mara Flutterflies. The wildly colorful Spring/Summer 2021 Signature capsule line was designed in collaboration with Dallas-based pop artist and part-time Montecito resident Donald Robertson.

The setting is a welcome one for Richie, who notes, “It’s a quiet place [where] I feel I can clear my mind. What gives me butterflies these days is nature,” she confides, and her regional hikes have taken her from the coast to inland waterfalls, allowing for “endless discoveries” along the way. “Through the pandemic I have found a new love for learning more about the planet,” she adds.

“What gives me butterflies these days is nature,” Richie confides. “Through the pandemic I have found a new love for learning more about the planet.

Describing his own witty and often madcap creative vision, Robertson says, “I just start taping [blank canvases], and miracles happen.” The Italian fashion house tapped the longtime Estée Lauder creative director—who has a penchant for using vivid gaffer tape—to create the collection’s Technicolor stripes, elongated female figures, and fluttering butterfly prints. Robertson’s imaginative drawings are now splashed across sneakers, cotton dresses, pants, shirts, and pencil skirts, plus epically cartoonish Pasticcino bags. “I believe happiness is a decision you make when you wake up,” Robertson says. “Rainbow-stripe jeans can help if you are having a tough day.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

The House That Wanderlust Built

A Montecito colonial goes California casual modern

A Montecito colonial goes California casual modern

Written by Cathy Whitlock | Photographs by Victoria Pearson | Interior Styling by Gillian Lawlee

Sharing a common bond with inveterate traveler Tamara Kaye-Honey, a California family looked to the interior designer—owner of the design studio House of Honey—for the renovation of a ’40s retreat in Montecito. “The clients travel extensively and wanted the home to feel like they were on vacation. They wanted a sense of timelessness and a form of escapism,” Kaye-Honey says. Since both client and designer are aficionados of the serene aesthetic of Aman Resorts, the hotel group’s signature use of natural materials, neutral hues, and landscapes that meld with the interiors provided the perfect starting point for the design.

Built in 1946, the 5,660-square-foot colonial was badly in need of a transformation that translated into a distinctively contemporary look the designer describes as “California casual modern with a twist of the unexpected.” Doing double duty as both architect and designer, Kaye-Honey says, “I tried to look to the past and respect the estate’s provenance yet make it modern, livable, and, of course, playful for a family of five. It was about respecting the history yet reinterpreting [it] for the present and the future.” In reimagining the space, her goal was to create a streamlined layout—preserving the footprint and “purity and honesty of the house’s incredible design”—while replacing the traditional period remnants of the ’40s, such as heavy decorative ironwork, brick, molding, and tile.

“Art is so important to me for every project, and this comes from an emotional place, not whether or not it works in the space. My clients were very drawn to organic and light colors and textures and movement.”

As with all design projects, the lifestyle of the clients was of utmost importance. Entertaining was at the top of their list, along with the active agendas of three teenagers. “On any given weekend, the entry can be transformed into a disco for teenagers or the living room into a screening room for watching movies. The furniture had to look chic but still have practicality,” Kaye-Honey says.

Both the clients’ and designer’s love of art also came into play in the way of large-format pieces. “Art is so important to me for every project, and this comes from an emotional place, not whether or not it works in the space. My clients were very drawn to organic and light colors and textures and movement.” Choosing works from abstract artists Mary Little and Arik Levy, the designer notes that “the playfulness and a sense of emotion in their pieces really set the tone for the interiors. Every room has its own identity, but there is a common thread that ties the house together.”

Art is also manifested in the home through unusual lighting that gives new meaning to the term conversation starter. Perhaps the most showstopping element of the house is found in the entry. Collaborating with Los Angeles–based artist and craftsman Jason Koharik, who is known for his sophisticated yet unorthodox take on sculptural lighting, Kaye-Honey explains, “Our choices of lighting are art pieces in and of themselves throughout the house. He created a custom entry lighting moment that was sculptural and would set the tone for the rest of the design.” The kite-like design, with its perforated metal shades hung from brass cords on the ceiling, extends across the area and lights up the walls in eye-catching angles. Koharik also designed the Salt cubes lights, sand-blasted white milk-glass cubes of varying depths that preside over the kitchen’s Bianco Lasa marble island. “I wanted to do something with movement that represents the ocean, salt, and how rock changes shape.”

Kaye-Honey, who has offices in South Pasadena as well as Montecito, incorporated a variety of exotic materials into the mix. Natural gray quarry stone, travertine, oak, basswood, walnut, rift oak, blackened steel, ribbed glass, and sandstone compose the bones of the soulful spaces, while nubby fabrics and metals accent the restrained décor, representing her penchant for fresh, modern interiors with a nod to the past.

Since the clients were initially drawn to Montecito by the San Ysidro Ranch’s beauty, Kaye-Honey and landscape architect Scott Menzel (working with Nydam Landscape Construction) brought the home’s lush grounds back to its natural state with oak trees framing sweeping views of the Pacific Ocean. Bifold Riviera Bronze steel-and-glass doors create a sense of indoor-outdoor living, complemented by European white-oak floors and Italian deco plaster. The designer also added functional wood pergolas with lighting, heat towers, and a Vertex shade awning, along with custom modular indoor-outdoor furniture.

The private retreat represents the best kind of collaboration, one in which designer, client, and artisans developed sympatico relationships that remained long after the final art was placed. The home reflects the true art and style of California living. •

See the story in our digital magazine

Roll with It, Baby

Viral videos on Instagram and TikTok have brought back roller skating in a big way.

Santa Barbara is a roller skater's paradise—bringing back unity, freedom, and joy in the pandemic

By Gina Tolleson | Photographs by Dewey Nicks | Styled by Jill Johnson for Loveworn

“Skating has been such a powerful outlet for me during the pandemic.”

Viral videos on Instagram and TikTok have brought back roller skating in a big way.

See the story in our digital magazine

Wild at Heart

The exotic world of John Edward Heaton

The exotic world of John Edward Heaton

Written by L.D. Porter | Photographs by Sam Frost

The best homes are, in essence, portraits of their owners, and John Edward Heaton’s Carpinteria residence is an inspiring example. Designed by architect Robert Garland for painter Howard Warshaw in the 1960s, it’s a cluster of handsome wood-sided buildings with a large barnlike art studio. For that reason, presumably, the house has always been inhabited by artists. (Although Heaton resists being labeled anything ending in “ist,” institutions exhibiting his stunning photographs—including the Santa Barbara Museum of Art—would argue the title applies.)

John Edward Heaton in his art studio surrounded by textiles from Atelier Xenacoj, the workshop of Kaqchikel Maya women weavers he founded in Guatemala.

Coming from Quinta Maconda—his antique-filled colonial residence/boutique hotel in Antigua, Guatemala, where he and his late wife, Catherine Docter, hosted guests like Francis Ford Coppola and Harrison Ford—Heaton was immediately attracted to the Carpinteria home’s architecture. “It’s an authentic California house; it was made in California,” he says. “In my journey I’ve always wanted to have houses of the place. I didn’t want to have a French house in Mexico or a Mexican house in France.” (The couple acquired their California outpost in 2017.)

The exterior may be Californian, but the home’s interiors are pure Heaton. Carefully curated objets culled from exotic travels coexist with bargained-for treasures from the Ventura County swap meet. Each room features at least one composition of driftwood, shells, or other detritus gleaned from Heaton’s daily beach perambulations. It’s a fearless aesthetic, guided by an insatiable curiosity about the world and its numerous cultures. His is a naturally educated eye.

Born in Paris to a French mother and an American father, Heaton spent his youth at boarding schools in England, France, and Switzerland. The first glimmer of his independent spirit emerged at St Andrew’s School in England, at age 8, when he and a schoolmate ventured without permission beyond the large abandoned chalk pit marking the perimeter of the school grounds. Their foray resulted in corporal punishment, but Heaton considered his painful bruises “stripes of glory,” evidence of a lesson learned: no pain, no gain. (He titled his first book of photographs Beyond the Chalk Pit.)

To be fair, Heaton’s restless spirit was inherited. His paternal ancestors were shipowners and traders from England who journeyed to America in the 17th century and plied the trade routes to the West Indies and China. (His great grandfather is said to be the first American to enter Beijing’s Forbidden City.) His father, “Jack” R. Heaton, was also an adventurer who explored Tahiti in the 1920s, Brazil and the Amazon in the 1930s, and the Chilean Andes in the 1940s. During the same period Jack won three Olympic medals—two silver and a bronze—as a bobsledder and skeleton racer.

That heritage is a mandate of sorts, but Heaton has surely lived up to it. After a stint at San Francisco’s Art Academy, he embarked on a three-year journey through Mexico, living in his Jeep and learning “fishy Spanish” working on a shark-fishing boat. Later he befriended followers of Maximón, a Mayan deity, and filmed their elaborate rituals. He accompanied the Dalai Lama to Russia. From 1977 onward he managed to compile an archive of 50,000 still images and 100 hours of film footage recording other extensive travels to Central America, Madagascar, India, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Irian Jaya, the Trobriand Islands, the U.S., France, and Peru.

Heaton also built a jungle eco-retreat (Rancho Corozal) so remote it lacks electricity; he restored several important Spanish colonial buildings in La Antigua Guatemala, a UNESCO World Heritage Site; and he founded Atelier Xenacoj, a workshop of Kaqchikel Maya women weavers who produce one-of-a-kind textiles using traditional techniques and vegetable dyes.

Over the years the travel press took notice of Heaton’s exploits, lauding his expertise as a hotelier while dishing on his dashing demeanor. (One Daily Mail writer dubbed him “impossibly handsome.”) And despite his refusal to embrace the artist label, both the Maison Européenne de la Photographie and The Latin American Library at Tulane University mounted exhibitions of his breathtaking black-and-white photographic portraits of everyday life in Guatemala. (His work also resides in numerous prestigious university collections and private collections.)

Ultimately, according to Heaton, it all boils down to exploring the world and the people in it: “Titles for me were not that important; it was what I was able to do. To sum it up, my life was spent trying to have a good life—not materialistically, but trying to have an interesting life where I could be an adventurer. Live in a beautiful house but go to the Ventura swap meet every Wednesday and chat with the people there. I think everybody’s interesting. For me, people at the Ventura swap meet are as interesting as the Lacandon Maya people I met in the jungle, because they’re people with stories.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

Art, Chocolate, and Pixie Dust

How Lisa Casoni and Heather Stobo captivated Ojai

How Lisa Casoni and Heather Stobo captivated Ojai

Written by L.D. Porter | Photographs by Victoria Pearson

We moved here without knowing one person,” says Lisa Casoni about her 2009 move from L.A. to Ojai with wife Heather Stobo. Eleven years later, it’s hard to imagine there’s anyone in Ojai the two don’t know. Joint owners of the Porch Gallery, located in a historic home in downtown Ojai, Casoni and Stobo literally have the most famous (and beloved) front porch in town. “All roads in Ojai lead to the Porch Gallery,” confirms Frederick Janka, executive director of Ojai’s Carolyn Glasoe Bailey Foundation.

Built in the early 1870s by John Montgomery, theirs is the third oldest building in Ojai and has experienced numerous permutations. The Baker family, who raised seven daughters in the house, added several rooms; later on the residence served as the town’s funeral home. By the time the couple discovered it, it already had an art gallery in the front room and offices in the back. At first they simply took over running the art gallery, which took off immediately. “People started gathering here on Sunday mornings, we started selling a lot, we started getting really great artists, and it almost literally went from zero to sixty in a few months,” Stobo says. They quit their day jobs and ended up buying the house, carefully renovating the private areas to include their living quarters.

“People came to us and said, ‘You know you have one of the most important and interesting buildings in Ojai, and you should fully take advantage of that and be good stewards of it,’” Casoni says, “And we took that to heart from day one.” The two use the house for nonprofit meetings and fund-raisers for organizations they support, including the Ojai Valley Defense Fund (Casoni’s on the board), the Ojai Women’s Fund, the Ojai Music Festival, the Carolyn Glasoe Bailey Foundation, and more. “The community is very important to us,” notes Stobo. “Our business is nothing without the community.”

The easygoing nature of Ojai’s residents contributed to their success. Early on, the late photographer Guy Webster—who shot album covers for The Rolling Stones, The Doors, The Beach Boys, and more—was instrumental in introducing the couple to interesting people, from visual artists to musicians. “Guy was seminal,” admits Casoni. “He cross-pollinated us with a bunch of different people.” It snowballed from there. Ultimately they followed Webster’s example, becoming “connectors” themselves. “We started introducing people to each other. It wasn’t ever about selling art, it was about connecting with people,” Casoni says.

But there’s more to the story, centering on the dynamic combination of the couple’s specific talents: Stobo has two art-related undergraduate degrees, in art history and photography (from Ohio’s Denison University and the San Francisco Art Institute, respectively) as well as a Master’s Degree in photography from California Institute of the Arts. Casoni’s background is steeped in sales and marketing. (She worked for Giorgio Armani and Prada, among others.) Casoni manages the “front of the house,” meeting and greeting visitors, while Stobo deals with technical issues, including website maintenance. It’s the perfect combo for running an art gallery.

Except that’s not all they do. Inspired by the life of flamboyant Ojai ceramicist Beatrice “Beato” Wood—who claimed she owed everything to chocolate, art books, and young men—they launched Beato Chocolates, using Wood’s original pottery molds and tapping local farmers for ingredients. During the COVID shutdown, Stobo and Casoni even managed to unveil a Beato Bar celebrating Ojai’s annual Pixie Month. It’s sprinkled with pixie dust from dehydrated pixie tangerines. (Pandemic frontliners receive Beato Bars for free.) And they’ve just unveiled an Artspeak line of candles that humorously riffs on art world tropes—the “Surreal” candle’s scent is “This is not a pipe.”

On any given day you’ll find several people happily lounging in the yellow butterfly chairs dotting Porch Gallery’s veranda; it’s clearly the town’s heartbeat. Casoni sums it up: “I always thought of Ojai as a small town but not small-minded.”

See the story in our digital magazine

Hats Off

Milliner Satya Twena's transcendent move to Ojai was in the stars

Milliner Satya Twena's transcendent move to Ojai was in the stars

Written and photographed by Blue Gabor

When California native Satya Twena came to Ojai from Manhattan with her restaurateur husband, Jeffrey Zurofsky, and daughter, Wish, she had every intention of remaining bicoastal. But the laid-back West Coast lifestyle soon eclipsed her life back East. “Ojai completely seduced me,” she says. “I would sit outside surrounded by trees, the moon, and the stars and think there is nothing more healing nor beautiful than life in nature.” She found herself shuttering her New York hat factory and moving her millinery operations to a converted garage in Ojai’s East End.

Vintage hat forms line her open-air studio, which is scattered with spiritual talismans and vestiges of old-world millinery. Here the interior designer–turned–hatmaker continues to masterfully shape and embellish each of her custom-ordered creations by hand, using materials that include beaver, rabbit, and mink felts and accents that might include gold work and all types of embroidery.

Twena and Zurofsky’s second child, a son named Sage, was born in Ojai, and the family is now settling into their full-time home. Dinners are procured, with Zurofsky’s culinary expertise, from their backyard garden and prepared in an open-fire oven. A spirit of creativity reigns, as the children might be found running around wearing only their own custom-fitted hats.

Twena’s hat making grew from a kitchen operation in an East Village walk-up to a chance opportunity to own one of the last-standing hat factories in the garment district, where she made hats for socialites and celebrities including Usher, Lady Gaga, and Oprah. Today every hat is a custom work of art, made just for the wearer, in a process that begins with a few questions, followed by a Facetime call and sketches. “My hats often symbolize the next rendition of who my client desires to be,” says Twena. She incorporates constellations of iridescent threads in her designs and embroiders mantras or intentions in the linings. Like those who wear them, no two Satya Twena hats are alike.

“I believe my clients seek my work because I do the spiritual and emotional work. I meet them as an open vessel with the sole purpose of fulfilling their desires and intentions, and the rest is magic.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

A Lifelong Love Affair

Beverley Jackson’s daughter reflects on the life and legacy of an icon

Beverley Jackson’s daughter reflects on the life and legacy of an icon

Written by Tracey Jackson

For years my mother, the late Beverley Jackson, had been calling herself the Doyenne of Montecito. Then at some point the borders expanded to include Santa Barbara as well. She would season the most mundane stories with the phrase: “I went to Vons, and four people said, ‘There is the doyenne,’” she’d say. I would do an internal eye roll. Oh, there goes mom again. Because, you know, doyennes are prone to exaggeration.

But I came to learn in her final years that mom really was the Doyenne of Santa Barbara. And her followers, fans, and acolytes covered the gamut, from those who worked in restaurants to celebrities and royalty, from socialites to the cashiers at Vons.

According to the Oxford dictionary, a doyenne is “a woman who is the most respected or prominent person in a particular field.” One might then ask what exactly was her field of expertise?

The woman did so many things over her nearly 92 years. She was a writer, a scholar of Chinese textiles, a wonderful photographer. She was the social columnist for the News-Press for several decades and then went on to write for other publications up until weeks before her death.

In her last years she was an artist, creating collages, pine-needle baskets, and jewelry. She was part of group shows and had a few one-woman exhibits. Pretty impressive in your nineties! Her books on China won awards. She lectured all over the world about bound feet and kingfisher feathers. She had very disparate and particular avenues of interest and expertise.

Yet no matter where she went or what she did or whatever side alleys of interests she wandered down, her heart and her allegiance and her love affair were always with Santa Barbara.

It wasn’t just geographical. We would return from exotic locales, and she would always say, “When I make that turn near the Rincon and see my mountains”—her mountains—“I realize there is nowhere in the world as beautiful as my Santa Barbara.” Again, for the record, her Santa Barbara.

When she walked along “her beach”—doyennes have an affinity for possessive pronouns—she would sigh, “There is no beach in the world to compare to this.”

The thing is, she meant it. While her house looked like someone picked it up from 1930s Shanghai and moved it to Montecito, her soul was always in Santa Barbara. And despite her ownership and adoration of the mountains and sea, it was really the people here she loved.

The people of Santa Barbara took her in at a time in her life when she needed that kind of shelter, and she gave back to them and the community nonstop for the rest of her life.

Many know of her today from elaborate stories she loved to tell about the movie stars who were her friends and the fabulous places she’d been. People knew her infectious laugh and the fact that no one could remember a time when she wasn’t around.

Mom left Los Angeles and moved to Santa Barbara in 1962. She was married with a young child. Within a year and half she would be a divorced single mom to an only child. That may not sound like much of a tragedy today, but in 1962 it was an uncommon occurrence. In fact, I was the only child of divorce at Laguna Blanca for most of my childhood.

Bev had been pretty protected by her parents. She went from their home to her marital home—a very comfy setup in Brentwood with a nanny for me and a guy that drove my dad around and worked around the house.

Suddenly she was on her own. No nanny. No husband. Just the two of us on a hilltop in Hope Ranch. She found herself unprepared for what life had dished out. But somehow, with her endless curiosity, steely determination, and spunky personality, she looked around and told herself, I am going to run this town.

Okay, I don’t know if she really said those exact words, and if you had ever asked her what she told herself during those early years, I’m not sure she would have put it in those terms. But knowing her the way I did, I know that is what she thought.

Santa Barbara in the 1960s was filled with the most interesting people. And it had its share of doyennes-in-residence: Pearl Chase, who preserved the community’s traditional charm and architecture; Lutah Riggs, the titanic midcentury architect; and Ganna Walska, the opera singer and creator of Lotusland. These were all true doyennes, and Bev longed to be one of them. But I don’t think she was projecting 60 years down the line. She simply wanted a place in the community, a position in society. And she wanted to make a home for us. Sure mom invented herself; most well-known people do. She turned herself into the woman she wanted to become. And she stuck with it until the end.

I have to say, being a doyenne has its perks, even posthumously. I called Lucky’s recently, in advance of what would have been Bev’s 92nd birthday. I wanted to take my kids to that restaurant and celebrate her. I called—no tables until late. I wasn’t speaking to the manager, so I asked the person’s name and how long he’d been there. “Over twenty years,” he replied. “Do you know who Beverley Jackson is?” I asked. “Of course,” he said, “everyone does.” I got the table.

So she’s still the Grande Dame—one of the most revered, honored, known residents of Santa Barbara. She worked for it, she earned it, and she coveted it.

See the story in our digital magazine

Through the Eyes of the Future

How Leah Thomas is redefining the environmental movement

How Leah Thomas is redefining the environmental movement

Written by Olivia Seltzer | Photographs by Mark Griffin Champion

If you’ve been on Instagram any time in the past six months, chances are you’ve seen countless graphics educating and informing on the Black Lives Matter movement, racism, and racial justice—to name a few. Twenty-five-year-old Ventura local Leah Thomas—or @greengirlleah, as her nearly 160,000 Instagram followers know her—is the creator of one such viral post. But hers was a little different from the other infographics that might have come across your feed. Instead of focusing on racial or environmental justice, it combined the two, addressing what Thomas calls “intersectional environmentalism.” The pioneering activist, who has written on the subject for publications such as Vogue and The Good Trade, is certainly more than qualified to inform on this topic, having studied environmental science and policy at Chapman University and worked on the PR and communications team for Patagonia—a leading “one-percent for the planet” corporation globally renowned for its passion for the preservation and restoration of the natural environment. I spoke with Thomas over Zoom to learn more about this relatively new term and how we can all be intersectional environmentalists.

How would you define intersectional environmentalism? Why is it important for people to become intersectional environmentalists? Intersectional environmentalism is a type of environmentalism that advocates for the protection of both people and the planet. It amplifies the voices and efforts of diverse individuals and marginalized communities and gives them a place in the environmental movement. I had worked at a lot of environmental organizations, and I had been in a lot of environmental spaces—I studied environmental science and policy at Chapman University—but I wasn’t seeing a lot of acknowledgment for environmental justice.