Wild at Heart

The exotic world of John Edward Heaton

The exotic world of John Edward Heaton

Written by L.D. Porter | Photographs by Sam Frost

The best homes are, in essence, portraits of their owners, and John Edward Heaton’s Carpinteria residence is an inspiring example. Designed by architect Robert Garland for painter Howard Warshaw in the 1960s, it’s a cluster of handsome wood-sided buildings with a large barnlike art studio. For that reason, presumably, the house has always been inhabited by artists. (Although Heaton resists being labeled anything ending in “ist,” institutions exhibiting his stunning photographs—including the Santa Barbara Museum of Art—would argue the title applies.)

John Edward Heaton in his art studio surrounded by textiles from Atelier Xenacoj, the workshop of Kaqchikel Maya women weavers he founded in Guatemala.

Coming from Quinta Maconda—his antique-filled colonial residence/boutique hotel in Antigua, Guatemala, where he and his late wife, Catherine Docter, hosted guests like Francis Ford Coppola and Harrison Ford—Heaton was immediately attracted to the Carpinteria home’s architecture. “It’s an authentic California house; it was made in California,” he says. “In my journey I’ve always wanted to have houses of the place. I didn’t want to have a French house in Mexico or a Mexican house in France.” (The couple acquired their California outpost in 2017.)

The exterior may be Californian, but the home’s interiors are pure Heaton. Carefully curated objets culled from exotic travels coexist with bargained-for treasures from the Ventura County swap meet. Each room features at least one composition of driftwood, shells, or other detritus gleaned from Heaton’s daily beach perambulations. It’s a fearless aesthetic, guided by an insatiable curiosity about the world and its numerous cultures. His is a naturally educated eye.

Born in Paris to a French mother and an American father, Heaton spent his youth at boarding schools in England, France, and Switzerland. The first glimmer of his independent spirit emerged at St Andrew’s School in England, at age 8, when he and a schoolmate ventured without permission beyond the large abandoned chalk pit marking the perimeter of the school grounds. Their foray resulted in corporal punishment, but Heaton considered his painful bruises “stripes of glory,” evidence of a lesson learned: no pain, no gain. (He titled his first book of photographs Beyond the Chalk Pit.)

To be fair, Heaton’s restless spirit was inherited. His paternal ancestors were shipowners and traders from England who journeyed to America in the 17th century and plied the trade routes to the West Indies and China. (His great grandfather is said to be the first American to enter Beijing’s Forbidden City.) His father, “Jack” R. Heaton, was also an adventurer who explored Tahiti in the 1920s, Brazil and the Amazon in the 1930s, and the Chilean Andes in the 1940s. During the same period Jack won three Olympic medals—two silver and a bronze—as a bobsledder and skeleton racer.

That heritage is a mandate of sorts, but Heaton has surely lived up to it. After a stint at San Francisco’s Art Academy, he embarked on a three-year journey through Mexico, living in his Jeep and learning “fishy Spanish” working on a shark-fishing boat. Later he befriended followers of Maximón, a Mayan deity, and filmed their elaborate rituals. He accompanied the Dalai Lama to Russia. From 1977 onward he managed to compile an archive of 50,000 still images and 100 hours of film footage recording other extensive travels to Central America, Madagascar, India, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Irian Jaya, the Trobriand Islands, the U.S., France, and Peru.

Heaton also built a jungle eco-retreat (Rancho Corozal) so remote it lacks electricity; he restored several important Spanish colonial buildings in La Antigua Guatemala, a UNESCO World Heritage Site; and he founded Atelier Xenacoj, a workshop of Kaqchikel Maya women weavers who produce one-of-a-kind textiles using traditional techniques and vegetable dyes.

Over the years the travel press took notice of Heaton’s exploits, lauding his expertise as a hotelier while dishing on his dashing demeanor. (One Daily Mail writer dubbed him “impossibly handsome.”) And despite his refusal to embrace the artist label, both the Maison Européenne de la Photographie and The Latin American Library at Tulane University mounted exhibitions of his breathtaking black-and-white photographic portraits of everyday life in Guatemala. (His work also resides in numerous prestigious university collections and private collections.)

Ultimately, according to Heaton, it all boils down to exploring the world and the people in it: “Titles for me were not that important; it was what I was able to do. To sum it up, my life was spent trying to have a good life—not materialistically, but trying to have an interesting life where I could be an adventurer. Live in a beautiful house but go to the Ventura swap meet every Wednesday and chat with the people there. I think everybody’s interesting. For me, people at the Ventura swap meet are as interesting as the Lacandon Maya people I met in the jungle, because they’re people with stories.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

Art, Chocolate, and Pixie Dust

How Lisa Casoni and Heather Stobo captivated Ojai

How Lisa Casoni and Heather Stobo captivated Ojai

Written by L.D. Porter | Photographs by Victoria Pearson

We moved here without knowing one person,” says Lisa Casoni about her 2009 move from L.A. to Ojai with wife Heather Stobo. Eleven years later, it’s hard to imagine there’s anyone in Ojai the two don’t know. Joint owners of the Porch Gallery, located in a historic home in downtown Ojai, Casoni and Stobo literally have the most famous (and beloved) front porch in town. “All roads in Ojai lead to the Porch Gallery,” confirms Frederick Janka, executive director of Ojai’s Carolyn Glasoe Bailey Foundation.

Built in the early 1870s by John Montgomery, theirs is the third oldest building in Ojai and has experienced numerous permutations. The Baker family, who raised seven daughters in the house, added several rooms; later on the residence served as the town’s funeral home. By the time the couple discovered it, it already had an art gallery in the front room and offices in the back. At first they simply took over running the art gallery, which took off immediately. “People started gathering here on Sunday mornings, we started selling a lot, we started getting really great artists, and it almost literally went from zero to sixty in a few months,” Stobo says. They quit their day jobs and ended up buying the house, carefully renovating the private areas to include their living quarters.

“People came to us and said, ‘You know you have one of the most important and interesting buildings in Ojai, and you should fully take advantage of that and be good stewards of it,’” Casoni says, “And we took that to heart from day one.” The two use the house for nonprofit meetings and fund-raisers for organizations they support, including the Ojai Valley Defense Fund (Casoni’s on the board), the Ojai Women’s Fund, the Ojai Music Festival, the Carolyn Glasoe Bailey Foundation, and more. “The community is very important to us,” notes Stobo. “Our business is nothing without the community.”

The easygoing nature of Ojai’s residents contributed to their success. Early on, the late photographer Guy Webster—who shot album covers for The Rolling Stones, The Doors, The Beach Boys, and more—was instrumental in introducing the couple to interesting people, from visual artists to musicians. “Guy was seminal,” admits Casoni. “He cross-pollinated us with a bunch of different people.” It snowballed from there. Ultimately they followed Webster’s example, becoming “connectors” themselves. “We started introducing people to each other. It wasn’t ever about selling art, it was about connecting with people,” Casoni says.

But there’s more to the story, centering on the dynamic combination of the couple’s specific talents: Stobo has two art-related undergraduate degrees, in art history and photography (from Ohio’s Denison University and the San Francisco Art Institute, respectively) as well as a Master’s Degree in photography from California Institute of the Arts. Casoni’s background is steeped in sales and marketing. (She worked for Giorgio Armani and Prada, among others.) Casoni manages the “front of the house,” meeting and greeting visitors, while Stobo deals with technical issues, including website maintenance. It’s the perfect combo for running an art gallery.

Except that’s not all they do. Inspired by the life of flamboyant Ojai ceramicist Beatrice “Beato” Wood—who claimed she owed everything to chocolate, art books, and young men—they launched Beato Chocolates, using Wood’s original pottery molds and tapping local farmers for ingredients. During the COVID shutdown, Stobo and Casoni even managed to unveil a Beato Bar celebrating Ojai’s annual Pixie Month. It’s sprinkled with pixie dust from dehydrated pixie tangerines. (Pandemic frontliners receive Beato Bars for free.) And they’ve just unveiled an Artspeak line of candles that humorously riffs on art world tropes—the “Surreal” candle’s scent is “This is not a pipe.”

On any given day you’ll find several people happily lounging in the yellow butterfly chairs dotting Porch Gallery’s veranda; it’s clearly the town’s heartbeat. Casoni sums it up: “I always thought of Ojai as a small town but not small-minded.”

See the story in our digital magazine

Hats Off

Milliner Satya Twena's transcendent move to Ojai was in the stars

Milliner Satya Twena's transcendent move to Ojai was in the stars

Written and photographed by Blue Gabor

When California native Satya Twena came to Ojai from Manhattan with her restaurateur husband, Jeffrey Zurofsky, and daughter, Wish, she had every intention of remaining bicoastal. But the laid-back West Coast lifestyle soon eclipsed her life back East. “Ojai completely seduced me,” she says. “I would sit outside surrounded by trees, the moon, and the stars and think there is nothing more healing nor beautiful than life in nature.” She found herself shuttering her New York hat factory and moving her millinery operations to a converted garage in Ojai’s East End.

Vintage hat forms line her open-air studio, which is scattered with spiritual talismans and vestiges of old-world millinery. Here the interior designer–turned–hatmaker continues to masterfully shape and embellish each of her custom-ordered creations by hand, using materials that include beaver, rabbit, and mink felts and accents that might include gold work and all types of embroidery.

Twena and Zurofsky’s second child, a son named Sage, was born in Ojai, and the family is now settling into their full-time home. Dinners are procured, with Zurofsky’s culinary expertise, from their backyard garden and prepared in an open-fire oven. A spirit of creativity reigns, as the children might be found running around wearing only their own custom-fitted hats.

Twena’s hat making grew from a kitchen operation in an East Village walk-up to a chance opportunity to own one of the last-standing hat factories in the garment district, where she made hats for socialites and celebrities including Usher, Lady Gaga, and Oprah. Today every hat is a custom work of art, made just for the wearer, in a process that begins with a few questions, followed by a Facetime call and sketches. “My hats often symbolize the next rendition of who my client desires to be,” says Twena. She incorporates constellations of iridescent threads in her designs and embroiders mantras or intentions in the linings. Like those who wear them, no two Satya Twena hats are alike.

“I believe my clients seek my work because I do the spiritual and emotional work. I meet them as an open vessel with the sole purpose of fulfilling their desires and intentions, and the rest is magic.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

A Lifelong Love Affair

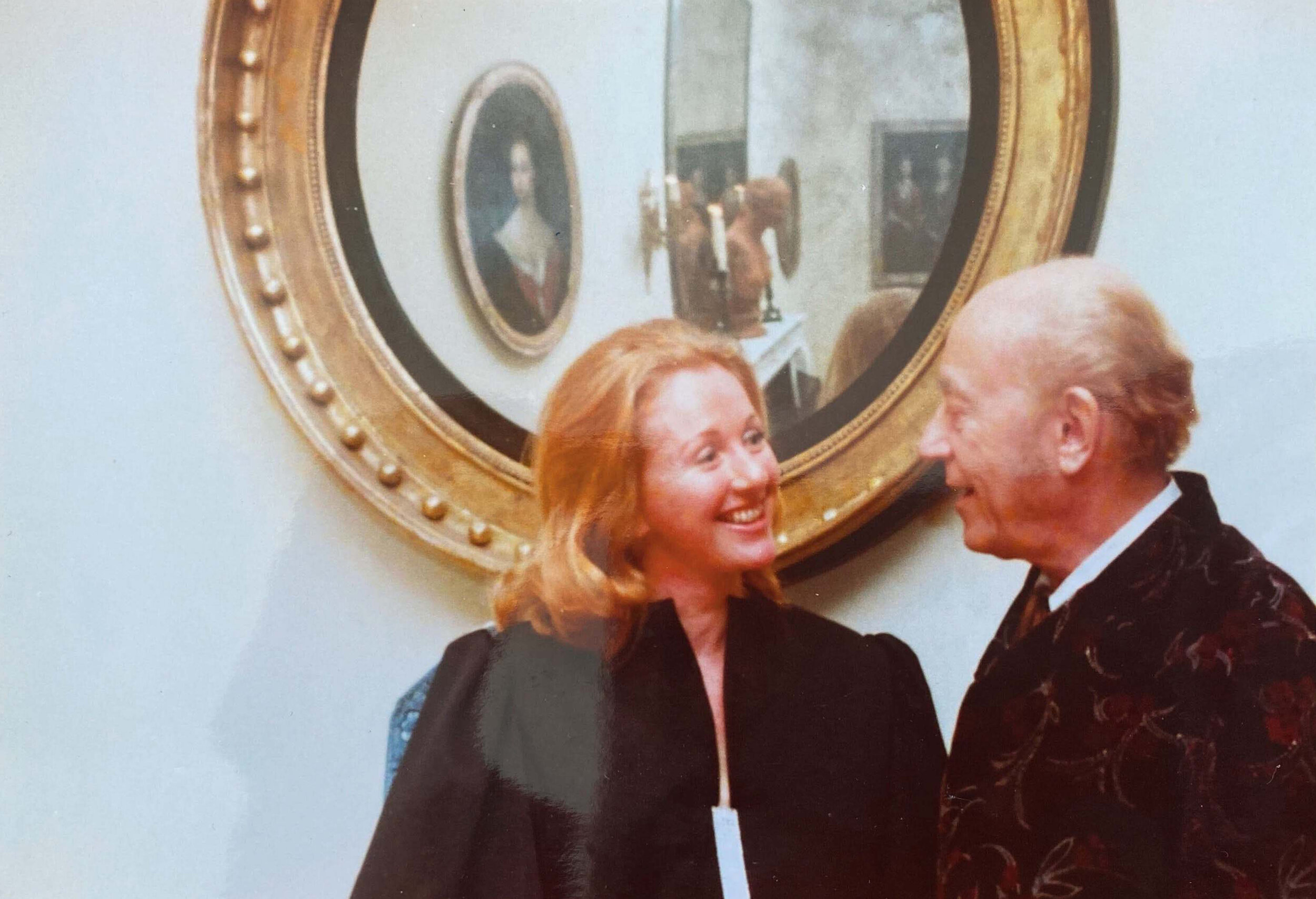

Beverley Jackson’s daughter reflects on the life and legacy of an icon

Beverley Jackson’s daughter reflects on the life and legacy of an icon

Written by Tracey Jackson

For years my mother, the late Beverley Jackson, had been calling herself the Doyenne of Montecito. Then at some point the borders expanded to include Santa Barbara as well. She would season the most mundane stories with the phrase: “I went to Vons, and four people said, ‘There is the doyenne,’” she’d say. I would do an internal eye roll. Oh, there goes mom again. Because, you know, doyennes are prone to exaggeration.

But I came to learn in her final years that mom really was the Doyenne of Santa Barbara. And her followers, fans, and acolytes covered the gamut, from those who worked in restaurants to celebrities and royalty, from socialites to the cashiers at Vons.

According to the Oxford dictionary, a doyenne is “a woman who is the most respected or prominent person in a particular field.” One might then ask what exactly was her field of expertise?

The woman did so many things over her nearly 92 years. She was a writer, a scholar of Chinese textiles, a wonderful photographer. She was the social columnist for the News-Press for several decades and then went on to write for other publications up until weeks before her death.

In her last years she was an artist, creating collages, pine-needle baskets, and jewelry. She was part of group shows and had a few one-woman exhibits. Pretty impressive in your nineties! Her books on China won awards. She lectured all over the world about bound feet and kingfisher feathers. She had very disparate and particular avenues of interest and expertise.

Yet no matter where she went or what she did or whatever side alleys of interests she wandered down, her heart and her allegiance and her love affair were always with Santa Barbara.

It wasn’t just geographical. We would return from exotic locales, and she would always say, “When I make that turn near the Rincon and see my mountains”—her mountains—“I realize there is nowhere in the world as beautiful as my Santa Barbara.” Again, for the record, her Santa Barbara.

When she walked along “her beach”—doyennes have an affinity for possessive pronouns—she would sigh, “There is no beach in the world to compare to this.”

The thing is, she meant it. While her house looked like someone picked it up from 1930s Shanghai and moved it to Montecito, her soul was always in Santa Barbara. And despite her ownership and adoration of the mountains and sea, it was really the people here she loved.

The people of Santa Barbara took her in at a time in her life when she needed that kind of shelter, and she gave back to them and the community nonstop for the rest of her life.

Many know of her today from elaborate stories she loved to tell about the movie stars who were her friends and the fabulous places she’d been. People knew her infectious laugh and the fact that no one could remember a time when she wasn’t around.

Mom left Los Angeles and moved to Santa Barbara in 1962. She was married with a young child. Within a year and half she would be a divorced single mom to an only child. That may not sound like much of a tragedy today, but in 1962 it was an uncommon occurrence. In fact, I was the only child of divorce at Laguna Blanca for most of my childhood.

Bev had been pretty protected by her parents. She went from their home to her marital home—a very comfy setup in Brentwood with a nanny for me and a guy that drove my dad around and worked around the house.

Suddenly she was on her own. No nanny. No husband. Just the two of us on a hilltop in Hope Ranch. She found herself unprepared for what life had dished out. But somehow, with her endless curiosity, steely determination, and spunky personality, she looked around and told herself, I am going to run this town.

Okay, I don’t know if she really said those exact words, and if you had ever asked her what she told herself during those early years, I’m not sure she would have put it in those terms. But knowing her the way I did, I know that is what she thought.

Santa Barbara in the 1960s was filled with the most interesting people. And it had its share of doyennes-in-residence: Pearl Chase, who preserved the community’s traditional charm and architecture; Lutah Riggs, the titanic midcentury architect; and Ganna Walska, the opera singer and creator of Lotusland. These were all true doyennes, and Bev longed to be one of them. But I don’t think she was projecting 60 years down the line. She simply wanted a place in the community, a position in society. And she wanted to make a home for us. Sure mom invented herself; most well-known people do. She turned herself into the woman she wanted to become. And she stuck with it until the end.

I have to say, being a doyenne has its perks, even posthumously. I called Lucky’s recently, in advance of what would have been Bev’s 92nd birthday. I wanted to take my kids to that restaurant and celebrate her. I called—no tables until late. I wasn’t speaking to the manager, so I asked the person’s name and how long he’d been there. “Over twenty years,” he replied. “Do you know who Beverley Jackson is?” I asked. “Of course,” he said, “everyone does.” I got the table.

So she’s still the Grande Dame—one of the most revered, honored, known residents of Santa Barbara. She worked for it, she earned it, and she coveted it.