Double Exposure

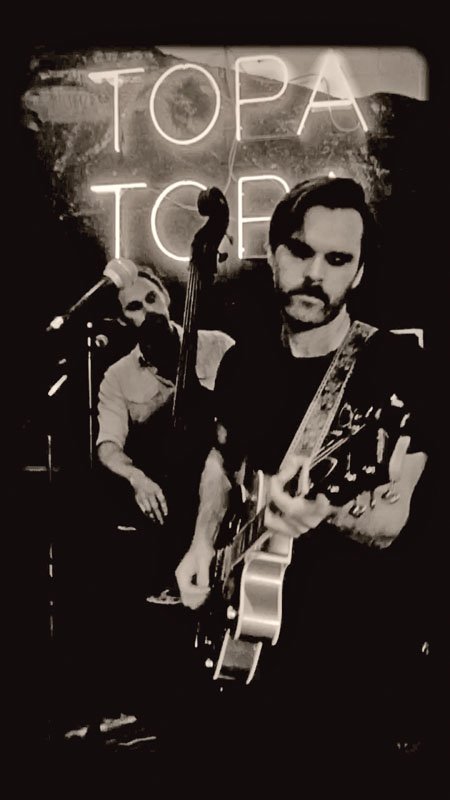

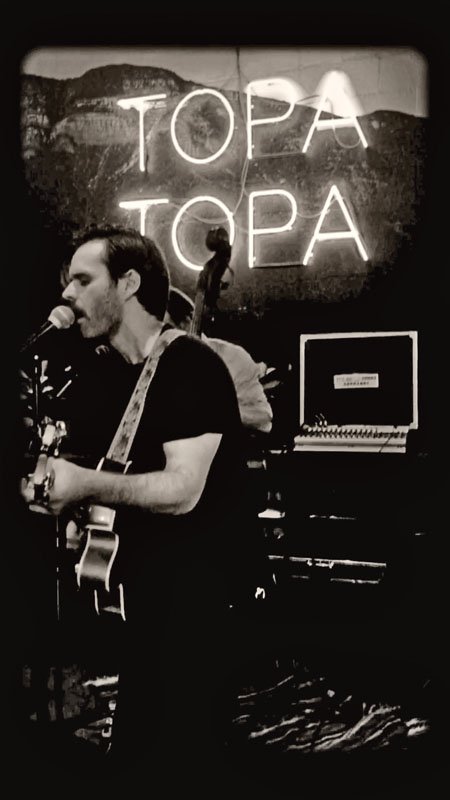

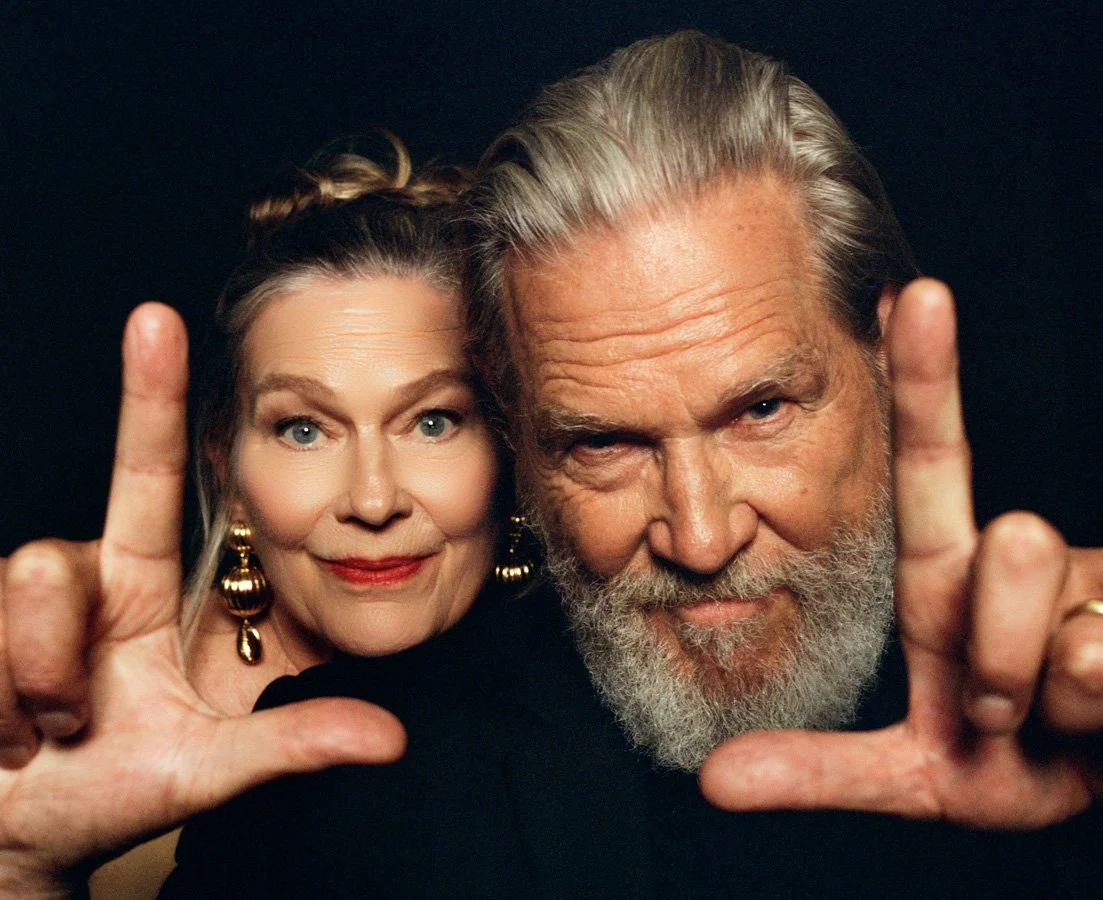

With their keen eyes for unforgettable images, actor Jeff Bridges and his wife, Susan—a lifelong photographer—take movie lovers and camera buffs behind the scenes in their tandem exhibitions at the Tamsen Gallery

With their keen eyes for unforgettable images, actor Jeff Bridges and his wife, Susan—a lifelong photographer—take movie lovers and camera buffs behind the scenes in their tandem exhibitions at the Tamsen Gallery

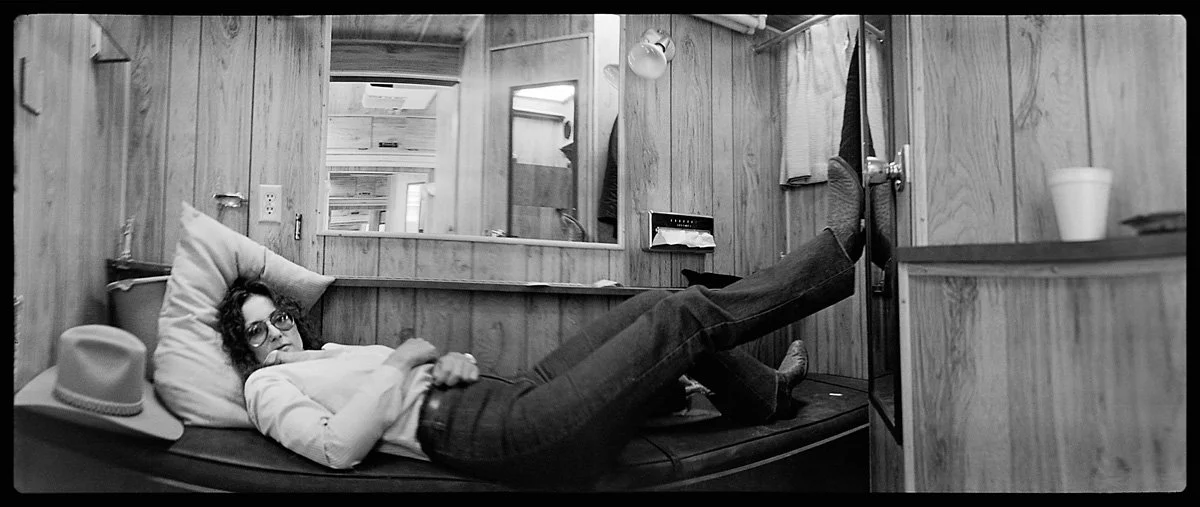

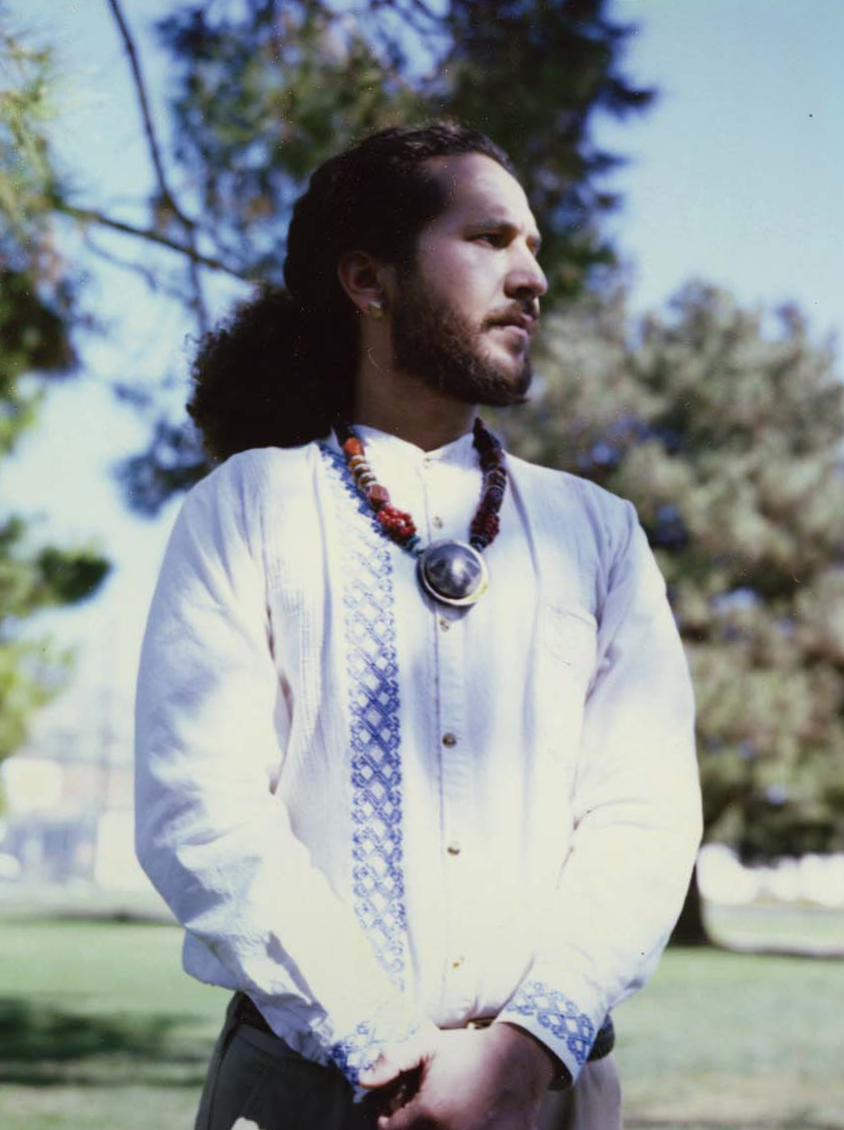

Filmed in 1979, Heaven’s Gate was a fictionalized version of the Johnson County War, and its sets and costumes recreated the Wyoming of the 1890s.

Jeff Bridges has favored a Widelux panoramic camera for his photography since Susan gave him one as a wedding gift.

“The negatives for all the [Heaven’s Gate] pictures from 1979 survived an earthquake, a fire, and a debris flow that destroyed many years’ worth of photographic work.”

Historically authentic garb for a wide range of characters—from townspeople to recent immigrants—helped establish the period look of Cimino’s movie.

Not just your ordinary selfies.

Jeff Bridges’ photographs will be exhibited at the Tamsen Gallery January 18–April 30, 2026. Reprints of his books of images —Pictures, Volumes 1 & 2—will be available in 2026 through JeffBridges.com. The exhibit Inside Heaven’s Gate: Behind the Scenes with Susan Bridges is on view at the Tamsen Gallery through December 31. 1309 State St., Santa barbara, tamsengallery.com

See the story in our digital edition

Super Star

Multimedia artist Russell Young reveals the hidden sides of cultural icons

Multimedia artist Russell Young reveals the hidden sides of cultural icons

Written by John Connelly

Photographs by Sam Frost

The British American artist Russell Young has a distinct man-in-black style that suggests, despite his humble origins and youthful challenges, he has lived a full and fascinating life. Young is a passionate survivor who has built a massive career working in various media, including painting, photography, screen printing, and sculpture. He is perhaps best known for his silk-screen paintings of cultural icons that incorporate Diamond Dust, a gritty, sparkling composite famously used by Andy Warhol.

Born in Yorkshire, England, in 1959, Young was adopted at the age of one after a brief respite at a foster home and a nunnery. He never knew his birth parents’ identities, but the uncertainty of his origins had a profound effect on him as a child and as a young artist. He grew up moving from town to town, where his adopted father, an electrical engineer, would take him to museums and to see films like The Magnificent Seven, establishing a lifelong fascination with California and the American West.

At 15, Young lied about his age so he could enroll in art school. He then moved to London, where he met commercial photographer Christos Raftopoulos, who became a mentor. Inspired by his tutelage, Young began photographing the early gigs of bands like Bauhaus, R.E.M., and The Smiths, which led to photo shoots and magazine spreads. This commercial work eventually landed him the album cover of the 1986 George Michael album Faith. The opportunity, Young says, “opened the Golden Gates” and was a “big influence” for him as an artist. What followed were more celebrity photo shoots, including sessions with Morrissey, New Order, and Björk, and pioneering music videos with a wide range of artists from The Brand New Heavies to Eartha Kitt.

After a move to New York City in 1997, Young introduced a new series of mug-shot “anti-celebrity portraits,” paintings that he says were “perhaps… a dig at my former career” as a commercial photographer. His following series, Dirty Pretty Things, introduced his now-signature use of Diamond Dust, and in 2005 Young created one of his most iconic works, Marilyn, Crying. The image, carefully cropped by Young, features a portrait of a raw, vulnerable Marilyn Monroe with eyes cast down away from the camera and one hand obscuring much of her face. The 100th anniversary of Monroe’s birth arrives in 2026, and Young is working with the Monroe estate to launch a campaign to honor that occasion. His new Marilyn 100 series debuts during Art Week in Miami this December.

Young has had several close calls with disaster, including a plane accident in Cleveland in his early 20s, a near-death experience in 2010 after contracting the H1N1 virus that put him into a coma for a week, and a narrow escape from the devastating 2017 Thomas Fire. All these challenges have continued to fortify a certain fearlessness and sense of survival, a daring and a perseverance in both life and his work. He regularly hikes alone for long stretches in the mountains of the Los Padres National Forest, swims out a mile in the moonlit ocean to look back at the lights of Rincon, and has spent extensive time camping and hiking the Channel Islands. “I like to isolate myself on the edge of the mountains or oceans,” Young says.

After living through 9/11 in New York, Young moved his family to Shepard Mesa in Carpinteria in 2002 and established an art studio in an old airplane hangar. He currently resides in a beach house on the Pacific Ocean and is renovating a nearly 100-year-old home in the Ojai Valley. A new studio in a former woodworking shop is located nearby. Young says he is drawn to and loves this “magical strip of flat lands surrounded by huge mountains” that produces our unique Mediterranean climate and “gives birth to and throws out very special people.”

“The West still taps into our most primal instincts.”

For him, one of those special people was Edie Sedgwick, the actor, model, and socialite who was born in Santa Barbara and became an “It Girl” in the 1960s and one of Warhol’s Superstars. Sedgwick died at age 28 from an accidental drug overdose following a period of drug use and a battle with mental health issues.

Young’s choice of Sedgwick—photographed by Warhol in 1965 in his iconic photobooth format at the height of her notoriety—for the cover of this issue of Santa Barbara Magazine embodies his interest in using glam shots of cultural icons to reveal the underbelly and fissures of American fame. His goal is to “interrogate the idealization of America’s history,” in particular that of the American West. According to Young, “The West still taps into our most primal instincts but also our most grandiose dreams.” His ongoing West series features “curiosities, knick-knacks, heirlooms, and fantasies of his own world built within the larger framework of the American drama.” Subjects include everything from the Marlboro Man cowboy to Elvis Presley, and Young’s choice and presentation of the images somehow capture “the exact edge where boylike wonder falls into violent truth.”

Recently Young has been stitching together his canvases to mimic the breadth of Hollywood wide screens, and they are intended to “pay homage and also to expose the artifice of our dreams.” Other subjects in Young’s newest works depict turn-of-the-century photographs of animals that, if not already extinct, are certain to become so soon. In another series, he enlarges flower paintings from the Dutch Golden Age to highlight the impossibilities of their unseasonal arrangements and expose their hidden messages. Both the animals and the flowers are “evocative of an earlier Young, when he was awestruck by things that seemed out of reach and would do anything to grasp onto their truth.”

The artist “is interested in secrets, those we keep, those we share, and those we are unwilling to confront.” With the impossible flower compositions of 17th-century Holland or an image of a fragile socialite starlet, he reveals that “a rose petal might, upon a closer look, be riddled with holes.”

See the story in our digital edition

A House That Rocks

Justine Roddick and Tina Schlieske play at home

Justine Roddick and Tina Schlieske play at home

Written by Lorie Dewhirst Porter

Photographs by Yoshihiro Makino

Imagine owning a 100-year-old house designed by a famous architect. How do you make it your own? Often the best solution is finding an interior designer skilled at combining iconic architecture with a client’s personal taste and lifestyle. Just ask Justine Roddick and Tina Schlieske, who enlisted interior design maven Tamara Kaye-Honey to apply glam-rock magic to an iconic George Washington Smith house—with spectacular results.

Built in 1920, Casa del Greco is the second house Smith designed and built for himself in Montecito, and is a classic example of Spanish Colonial Revival style. Following Smith’s death in 1930, Casa del Greco passed through several owners’ hands before Roddick and Schlieske discovered it in 2004. For at least a decade after moving in, the couple were torn between reverence for Smith’s creation and the desire to feel at home. “We just weren’t really ready to do anything for a long time,” Roddick says.

But like many homeowners who suddenly found themselves in lockdown, the owners found that the pandemic provided the impetus they needed to personalize their environment. They contacted Kaye-Honey, founder of House of Honey, whose work Schlieske had admired online. At their initial meeting, Roddick recalls outlining their needs and describing their aesthetic: “We don’t want to take anything away from what was originally here; we just want to make it feel like our home. Tina’s vibe is very ’60s, and I’m all disco ’70s. What can you do with that?”

Quite a bit, as it turned out. Roddick’s fondness for the swinging ’70s—an era she experienced in her native England—appears in Kaye-Honey’s treatment of the dining room, with its glamorous dark green walls and elegant starburst chandelier suspended over an elliptical dining table surrounded by streamlined vintage metal-and-leather chairs. As Roddick says, “London is still very much part of my DNA.”

Speaking of DNA, Roddick gleaned her business experience early on, working for her parents, who founded The Body Shop, the natural beauty-product company that helped shape ethical consumerism worldwide. Working for The Body Shop brought Roddick to California. She eventually settled in Santa Barbara, creating an international chain of retail shops—Coco de Mer—with her sister, Sam. (They sold the company in 2011.) Currently Roddick is copresident of AHA!, a local nonprofit that helps teenagers, educators, and parents tackle apathy, prevent despair, and interrupt hate-based behavior. She’s also a trustee of The Roddick Foundation, a charity that supports projects involving human rights and social and environmental justice.

The home represents a peaceful coexistence of

Spanish Colonial Revival and urban style.

The Roddick-Schlieske household is a musical one. “Music is at the heart of the family’s passions,” Kaye-Honey says, “and a through line of the design and approach of the home.” It could hardly be otherwise, when you consider that Schlieske is an actual rock star. With her bands, Tina and the B-Sides and the Graceland Exiles, her musical repertoire includes Americana, blues, punk, and her latest passion, jazz. Locally, Schlieske has performed at the Lobero and the Granada Theatres; her annual shows at Cold Springs Tavern on Memorial Day and Labor Day have thrilled audiences for a dozen years. She often performs in her hometown of Minneapolis, where she has a dedicated and passionate following. (Prince, another Minneapolis native, was a fan; Schlieske appeared as an extra in the film Purple Rain.) “I’m so thankful that people still want to hear me sing at this age,” she says. “I’ll go anywhere I get invited to play.”

Kaye-Honey followed her clients’ musical mandate by transforming their formerly staid living room into a serene listening salon. Anchored by an inviting circle of six swoon-worthy tub chairs upholstered in emerald green velvet, the space features Schlieske’s impressive vintage sound equipment displayed on a custom-built shelving system by Jason Koharik. A colorful portrait of Elvis Presley by James Holdsworth presides over the surroundings. But distinctive Smith trademarks remain intact: the original wood-beam ceilings painted by Lutah Maria Riggs, the rough plaster walls, and the magnificent tile-clad circular staircase leading to the second floor. The home represents a peaceful coexistence of Spanish Colonial Revival architecture and sophisticated urban style.

The pièce de résistance—and likely the most beloved room in the house—is a former playroom that Kaye-Honey remade into a bar–performance space with midnight blue walls. “The best thing we did, without question, was the back bar,” says Roddick. “It used to be our kids’ playroom, and when [Mayla and Atticus] moved out, we’re like, Now we want a big kids’ playroom.” The bar itself, with four graceful stools, is indeed a star. The scalloped marble top and sleek brass base were also created by Koharik, as were the dramatic glass pendants illuminating the room. There’s even a performance stage fashioned out of vintage rugs. As Kaye-Honey says, “We playfully pushed the period home to its rock ‘n’ roll limits.”

See the story in our digital edition

A Delicious Revolution

Alice Waters returns to Santa Barbara with her sustainability movement

Alice Waters Returns to Santa Barbara With Her Sustainability Movement

Written by Jennifer Blaise Kramer

Photographs by Sara Prince

Alice Waters has been spending significant time in Santa Barbara. It’s not just for the sunshine; it’s a full-circle moment for the chef to be visiting restaurants and ranches on the American Riviera, where she started her academic career at UCSB before transferring to Berkeley. That move altered her life, igniting a love for food and politics that would turn the student into a lifelong restaurateur, author, and activist.

“I was just having too much fun in Santa Barbara, and my friend said there’s something going on at Berkeley—let’s transfer. We walked right into the Free Speech Movement, and it changed my life. I really understood the power of a group of people who were committed to making change,” Waters says, adding that from a very tender age, activism was tied up with her love of food. “Then I went to France, and the rest is history.” Waters opened Chez Panisse restaurant in Berkeley in 1971. In 1995 she started the Edible Schoolyard Project, which fused her passions—food, education, and equality—and eventually created change.

“It’s extraordinary how one woman can plant a seed for an edible schoolyard and for that to grow and carry to feed children all over the world”

“I had a vision of how we could plant a garden over in a vacant lot and build the cafeteria on the asphalt and use these portable buildings for kitchen classrooms, but I never imagined teaching gardening or cooking,” she says. The concept caught on quickly, and kids loved cooking the food of, say, the Middle East while studying geography. “I understood again the power of food, the power of nature, to be outside where you can grow your own food, and how calculations in math class could help you plant seeds. It was hugely successful, but I didn’t know it was going to grow to 6,500 schools around the world,” she says.

Now celebrating 30 years of the Edible Schoolyard, Waters is shifting her focus to school lunches. School-supported agriculture is her current passion, bringing her to fund-raising events and farmers markets nationwide—in Washington, D.C., she recently won the Julia Child Award and Kamala Harris showed her around—to raise money and awareness. It’s a concept that could also make waves, benefiting both the students (by offering them healthier options and locally grown food) and the farmers (by boosting their economy).

“The idea is for the schools to buy directly from farmers, because when you buy directly, you leave out the middleman, and the farmer or the rancher gets the money,” says Waters, whose next book, School Lunch Revolution, will be published in 2025. “We did this at Chez Panisse, and I know it will stimulate local farming in a way that will build the community.”

In Santa Barbara, Waters met with farmers, growers, and thinkers, such as Mary Ta. She’s a kindred spirit who’s combining regenerative farming with biophilia (an expanded appreciation for nature) at her Skyfield Ranch, which boasts 80 acres of organic farmland in the Los Padres National Forest. Waters then ventured up to Santa Ynez, over to Lotusland, and downtown to the Saturday morning farmers market. “I just couldn’t believe the biodiversity of the produce, all different colors of raspberries, and children everywhere,” she says. She reunited with an organic farmer she knew in the ’60s and told him what she’s been up to, and he quickly volunteered to help.

“So many people in Santa Barbara care about the environment—I just might have to move back!” she says. “I love the proximity to the ocean, the care everybody feels to the land. And the whole UC system could be critical to this idea of school-supported agriculture. And what better place to do this than the whole state of California?”

The city showed up for Waters on one fall evening, when she captivated the community at a dinner hosted by sisters Belle Hahn and Lily Hahn Shining of the Twin Hearts Foundation. The event benefited the chef’s school-supported agriculture mission in Washington, D.C., where Waters hoped to raise awareness and bring some actual farmers to the tables where big changes take place.

“Everyone gave generously to the cause because of Alice. She is pure heart,” says Gina Andrews of Bon Fortune, who oversaw the garden party at a private estate in Montecito. In addition to arranging strategic lighting and decor, Andrews made thoughtful decisions that aligned with the chef’s philosophies. In lieu of florals, Truman Davies opted for vegetable centerpieces that wouldn’t distract from the food. Upon hearing of Waters’ love for sea urchins, Andrews got local commercial fisher Stephanie Mutz to bring the seafood, which the Gala restaurant team prepared for the party. And in true Waters fashion, Andrews made sure Mutz also had a seat at the table. “We wanted to tether that localism and celebrate our biodiversity and the gifts from the sea that make our area so rich,” Andrews says.

Guests also enjoyed heirloom tomatoes from Tutti Frutti Farms, pan-roasted Liberty duck, and Santa Barbara black cod with local wine pairings. “While every element of the decor was intentional and lovely, it was never about the design,” Andrews says. “The focus was on the food and honoring the people and sources that contribute to the message that Alice has championed for decades.”

“So many people in Santa Barbara care about the environment—I just might have to move back!”

Cohost Belle Hahn continues to be inspired by Waters. “Alice was a hero of mine from early childhood, as I believed that she was the original, all-time goddess of the slow-food movement,” says Hahn. “It’s extraordinary how one woman can plant a seed for an edible schoolyard and for that to grow and carry to feed children all over the world, including this mission now for school lunches and edible classrooms.” Hahn, who shares a passion for regenerative farming as executive producer of Feeding Tomorrow, bonded with the chef around creating opportunities where children can learn and grow.

“The education around regenerative agriculture and this shift back into the simple abundance of life is the catalyst of the delicious revolution Miss Waters talks about,” says Hahn. “And those are the waters that I want be a part of.”

See the story in our digital edition

Sculpting the Future

Goleta’s clay studio Reaches Beyond Southern California

Goleta’s Clay Studio reaches beyond Southern California

Written by Lorie Dewhirst Porter | Photographs by Bruce Heavin

Don't Miss •

Artist Trunk Show

• SBMA

Nov 16 •

Don't Miss • Artist Trunk Show • SBMA Nov 16 •

“We’ve been really focused on local all this time. We can still serve our community, but we also believe it would be a really amazing experience to come from far away and be able to study here.”

For the past three years, the nonprofit Clay Studio in Goleta has been a local community hub for creatives who love the ceramic arts. The 24,000-square-foot facility boasts a state-of-the art ceramics studio, a 3D clay printer, potter’s wheels, kilns, and plenty of room to work. Current programming includes weekly classes, workshops, artist’s talks, and gallery exhibitions.

But there’s more. Clay Studio is getting ready for the future, with a new executive director and gallery coordinator, Matt Mitros. An artist in his own right, Mitros spent the past 16 years in academia, teaching ceramics at the university level. His decision to relocate to California from Illinois to lead Clay Studio was initiated and encouraged by philanthropist Lynda Weinman, who had attended a 3D clay-printing workshop taught by Mitros.

Weinman, who cofounded the online learning platform Lynda.com, helped launch Clay Studio in 2020 and sensed from the start that it could become a global resource for creative exploration and design.

“We’ve been really focused on local all this time,” Weinman says. “We can still serve our community, but we also believe it would be a really amazing experience to come from far away and be able to study here.”

To that end, Mitros plans to feature intensive workshops lasting several days, taught by renowned experts from all over the world and open to local as well as national and international participants. New equipment will be added—3D printers for clay and plastic—and the curriculum will be expanded to include emerging fabrication technologies.

“We want to be a place where we can say, ‘What do you want to do? We have a solution for you, and we welcome your ideas,’” says Mitros.

Cactus vase with various glazes and luster. 3D-printed weavzy object. All by Lynda Weinman.

In reality, some of this vision has already been happening in the Clay Studio’s warehouse-like space, where students from Massachusetts Institute of Technology have spent the past two summers working on-site. Their doctoral program, called Programmable Mud, resulted in fabrication of a brick that can deflect heat on the outside and retain heat on the inside, potentially a huge game changer for the global construction industry. “It could become the Central Coast Bauhaus,” Mitros concludes, referring to the Clay Studio, “with people sharing ideas.”

See the story in our digital edition

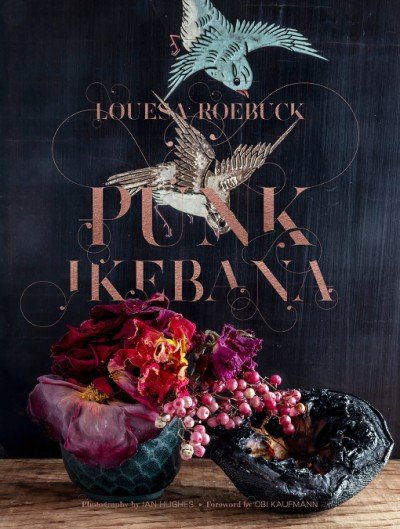

Floristry for the Future

Reimagining the art of arrangements and installations

Reimagining the art of arrangements and installations

Text and images excerpted from Punk Ikebana (Cameron Books) by Louesa Roebuck with photographs by Ian Hughes

Ojai-based floral designer Louesa Roebuck, author of Foraged Flora, is known for her ability to interpret the traditional “way of the flowers” from her own unique perspective, creating stunning installations with seasonally gleaned and foraged materials from California. Her artistry celebrates the natural world just outside our doors. Here, Roebuck shares with us a slice of her lush, enchanting world—and a few musings on the powerful meaning of "punk ikebana."

I Silence. In ikebana, this particularly refers to a quiet appreciation of nature, free of noise or idle talk. I agree that to hear more clearly, to see more deeply, we need to learn to quiet the easily distracted “monkey brain,” the self—although I do reject the idea of humans as somehow separate from “nature.” And sometimes it’s fun to gossip while working!

“Local fruit is a new love, its offerings changing monthly, even weekly: pineapple guava, persimmons, citrus galore, passion fruit, cherimoya, and our own pomegranates.”

II Minimalism. Here’s where my punk aesthetic comes in. I’m a bit of a rebel and a maximalist more often than not. I do strive for harmony and balance in my compositions always, but I also love the glam, the sexy, the louche, even. All of that said, the use of negative space is intrinsic to this practice, and often a foreign aesthetic concept to Westerners. I lean into both vibes.

“You ask, “How long will floral creatures, these ‘arrangements,’ last?” I answer

every time, “I don’t care; beauty is not about duration.””

III Harmonious Form and Line. When you gather and glean seasonal and local flora and compose naturally, you will find that harmony comes effortlessly. The longer, deeper, more studied, or more expansive your search becomes, the more treasures you find just outside your doors. Mother Earth contains all of the multitudes where they need to be; there’s no need to fly flora in from anywhere else.

See the story in our digital edition

Bellosguardo

Heiress Huguette Clark’s extraordinary mansion is poised to welcome visitors

Heiress Huguette Clark’s extraordinary mansion is poised to welcome visitors

Written by Joan Tapper | Photographs by Dewey Nicks

Bellosguardo. The name means “beautiful lookout,” but that doesn’t begin to describe just how breathtaking the property actually is, let alone convey the astonishing level of popular fascination with the estate and the story of the last owner.

Perched on a cliff at the east edge of Santa Barbara, Bellosguardo commands a 360-degree view of the Pacific, the city, and the mountains. The mansion at the center of the 23-plus acres was built in 1936 by Anna Clark—widow of W. A. Clark, who had amassed a fortune in the copper industry—to replace an earlier home. This was no modest getaway. For herself and her daughter Huguette, Anna commissioned a formal U-shaped 18th-century French-style structure of more than 23,000 square feet and 27 rooms from architect Reginald Johnson, who had also designed the Santa Barbara Biltmore not far away. The interiors were grand, with ornate flourishes like wood paneling, detailed cornices, and elaborate chandeliers. There were six suites, a music room, a library, and an artist’s studio where Huguette could paint or pursue photography.

The grounds were similarly magnificent, from the floral-design stone court in front of the mansion to sweeping lawns and a gorgeous rose garden.

Anna and Huguette kept their main residence in New York City but made Santa Barbara a regular getaway until around 1953, enjoying the house, welcoming friends and guests, and participating in the town’s social life. After that, caretakers lived on the estate and kept it up for owners who never came again. Even after Anna died in 1963, and Huguette inherited Bellosguardo, the instructions were to keep everything as it always had been. And so it was. Though the furniture was covered, and the rugs were wrapped, nothing inside was altered, and the Chrysler convertible and Cadillac limousine remained parked in the garage. The house was largely unseen for the next nearly 70 years, tantalizing Santa Barbara residents who wondered what it was like inside the walls of the estate.

“After a long road of preparation, Bellosguardo will open its doors to small public docent-led tours.”

Huguette died on May 24, 2011, having spent her last two decades living in hospital rooms in Manhattan. But she kept up ties and correspondence and although her bequests and the terms of her will became embroiled in legal wrangling, she left the Santa Barbara property to the Bellosguardo Foundation. Their vision, says Sandi Nicholson, who’s been on the board since its inception, is to “open it as a dynamic venue for cultural and artistic events, while showcasing the unique history of the Clarks and specifically Huguette Clark’s contribution to the arts.”

And now, at last, that’s about to happen. After a long road of preparation Bellosguardo will open its doors to small public docent-led tours in the next couple of months. Visitors will be able to see original furnishings, objets d’art, and paintings. Walking through the high-ceilinged foyer, they’ll enter the main hall, which stretches toward each of the wings and reveals views of the reflecting pool in back, flanked by 80-year-old orange trees. Family portraits line the walls here, not only of W. A. Clark, his wife Anna, and Huguette but also Huguette’s sister, Andrée, who died young.

To the left lie two rooms crafted in Europe and installed here from another Clark property in New York: the reception room, with its exquisite paneling and painted muslin ceiling, and the imposing dining room with antique chairs arrayed around the table.

In the other direction lies the elegant music room, dominated by two Steinways and two

of Anna’s harps. The library is next, with bound volumes filling the elaborate shelves and a portrait of Andrée over the fireplace. Then there’s the bureau room, Anna’s office. European in origin, it’s even more intricately carved than the others and includes large cartouches with French-inspired pastoral scenes.

The highlight of the tour, though, is certainly the studio/gallery, in which the foundation has hung some 50 of Huguette’s own paintings brought back from New York and recently displayed at the Santa Barbara Historical Museum—images of models in elaborate dress, self-portraits, still lifes, even pieces depicting a New York cityscape. Painted over several decades, they reveal Huguette’s accomplished hand and her attention to her art.

Notes Nicholson, “The foundation will build upon the tours and gradually increase public access, not only to the house but also to the grounds, so that people can enjoy this momentous gift that the Clarks and Huguette gave to the community.” bellosguardo.org.

See the story in our digital edition

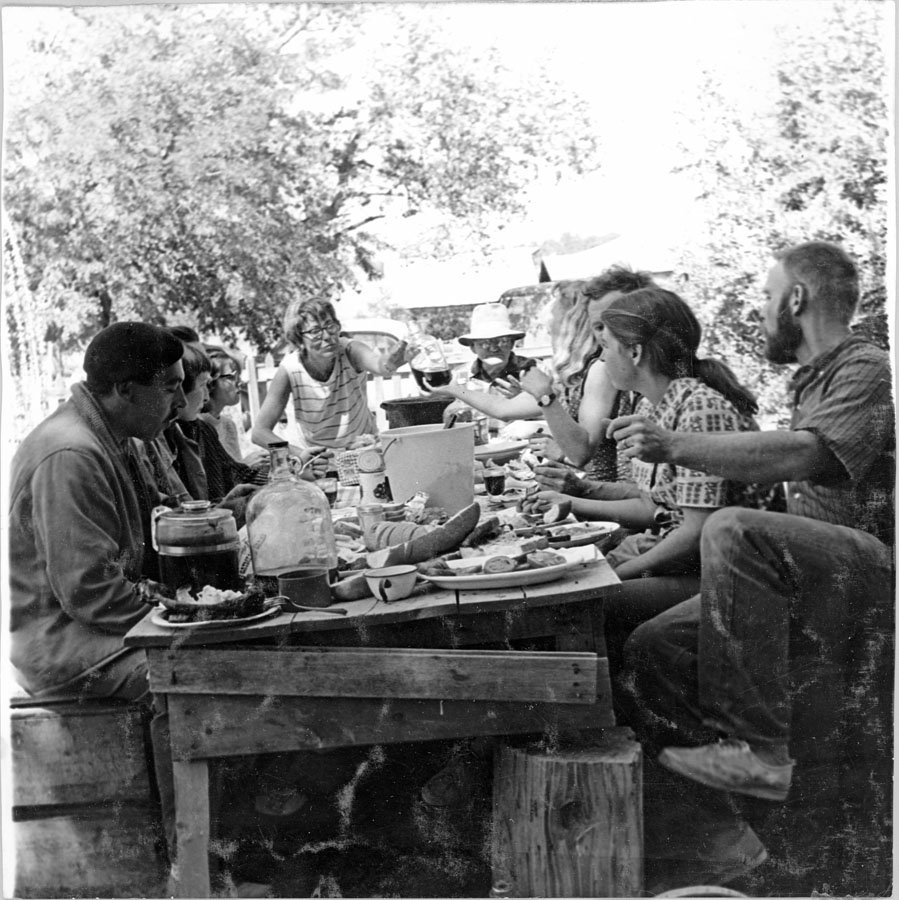

Bohemian Rhapsody

The Santa Barbara Historical Museum takes a nostalgic look back at the infamous enclave once thriving on Mountain Drive

The Santa Barbara Historical Museum takes a nostalgic look back at the infamous enclave once thriving on Mountain Drive

Written by Josef Woodard

Photographs: Chiacos (Elias) Mountain Drive Papers, Gledhill Library, Martin (Ed) Photograph Collection, Neely Family Photograph Collection, Peake (Michael) Mountain Drive Photograph Collection, Santa Barbara Historical Museum,

Tooling along Mountain Drive, by car or bicycle, is a classic Santa Barbara ritual. The ribbon of road connecting Mission Canyon with Montecito is speckled with varied architecture—including houses rebuilt after the 2008 Tea Fire—and offers a stunning panoramic view of ocean and city.

“Mountain Drive was known as a haven for artists, societal rebels, revelers, and general free-thinkers.”

But the 21st-century Mountain Drive barely hints at this area’s yesteryear, when it was home to a thriving bohemian enclave. Between the late 1940s and late ’60s, spanning such movements as the Beat era and hippiedom, Mountain Drive was known as a haven for artists, societal rebels, revelers, and general free-thinkers seeking to create a community beyond the borders of conventional society. The range of festivities and rites up on the Drive featured a raucous, clothing-optional grape-stomping event (its product destined for the Pagan Brothers label), the “Pot Wars” ceramic festival and competition, variations on Maypole ceremonies, and even a celebration of Scottish poet Robert Burns’s birthday. Music of all types provided a ragged, constant serenading presence in those hills.

To get a taste of Mountain Drive’s mythic, maverick past, proceed to the Santa Barbara Historical Museum’s fascinating archival exhibition Memories of Mountain Drive. If the museum has generally leaned into the milder side of Santa Barbara history, this show surprises us with its wilder slice of local lore. Organized by Chris Ervin, head archivist of the museum’s Gledhill Library, and on view through February 28, the exhibit draws on the ample photo archives of Elias Chiacos (author of 1994’s Mountain Drive: Santa Barbara’s Pioneer Bohemian Community) as well as the museum’s extensive oral-history project. In all, the show takes us back and drops us into the intoxicating—and intoxicated—inner life of Mountain Drive in its storied heyday.

Sensory input in the museum gallery includes a folksy soundtrack by the Scragg Family, led by influential bluegrass/folk musician Peter Feldmann, and a looping clip from the quirky John Frankenheimer–directed sci-fi film, Seconds, from 1966, which put Mountain Drive on a broader map of public awareness (although the film, with James Wong Howe’s Oscar-nominated cinematography, achieved only cult-film status). In Seconds Rock Hudson appears as a reborn manifestation of a midlife-crisis-afflicted East Coast banker. He falls in with a free-spirited woman (Salome Jens) who lures him up to Santa Barbara for the bacchanalian revelry of the grape stomp. They end up naked and stomping in lockstep with a vast vat of unclad, unrepressed humanity, high up in the 805. Ironically, the film’s ultimate Faustian message negates the societal escapism represented by the hardcore Mountain Drivers.

“The range of festivities and rites up on the Drive included the raucous, clothing-optional grape-stomping event.”

One defining aspect of the Mountain Drive story relates directly to the tragic legacy and recurring fear of fire in the area. Mountain Drive’s founder and culture shaper, Bobby (Robert McKee) Hyde, acquired 50 acres of fire-scorched land for a relative pittance in 1940 and sold parcels to like-minded free spirits and bohemians-in-training. They built humble houses, mostly of adobe (“unencumbered by building codes,” according to the show’s wall text) and, with 40 families involved by the early ’60s, established a communal enclave of societal outliers.

Fast-forward to the calamitous 1964 Coyote Fire, when many homes were destroyed--including Hyde’s abode. Fire paved the way for the Mountain Drive experiment and fueled the beginning of its end.

Scenes of Mountain Drive, as seen here, included vintage costumes and traditions, humble home-building (usually with adobe) with help from neighbors, and downtown appearances on floats in the Fiesta parade. Elias Chiacos’ 1994 book Mountain Drive: Santa Barbara’s Pioneer Bohemian Community is the most thorough chronicle of the community and history to date.

We gain insights about life on Mountain Drive through black-and-white images on one wall and from a large touch-sensitive screen on which we can scroll through issues of the humble but informative Mountain Drive News and the Grapevine. Less savory aspects of community life include a strong strain of prefeminist sexism, as detailed in Susan Sisson’s oral history.

Another key charismatic Mountain Drive figure was Bill Neely—potter, musician, magnetic mischief-maker, and organizer. According to local resident Dick Johnston, Neely was “about half good and half evil.” One Sandy Hill spoke about a friendly argument in design between Bill’s peasant pottery and the more refined work of Ed Schertz. For his part, Schertz spoke more generally about the Mountain Drive philosophical m.o.: “It was so open…if you weren’t (of) a mass-society orientation, if you were interested in freedom and the exchange of ideas.”

Bobby Hyde’s son Gavin touched on another truth about the place/experiment, commenting that “dad said that people don’t choose the land. The place chooses the people.”

That was then. This is the real estate–booming now. But memories of Mountain Drive, personal and archival, titillate the imagination about another life, time, and place in Santa Barbara. www.sbhistorical.org

See the story in our digital edition

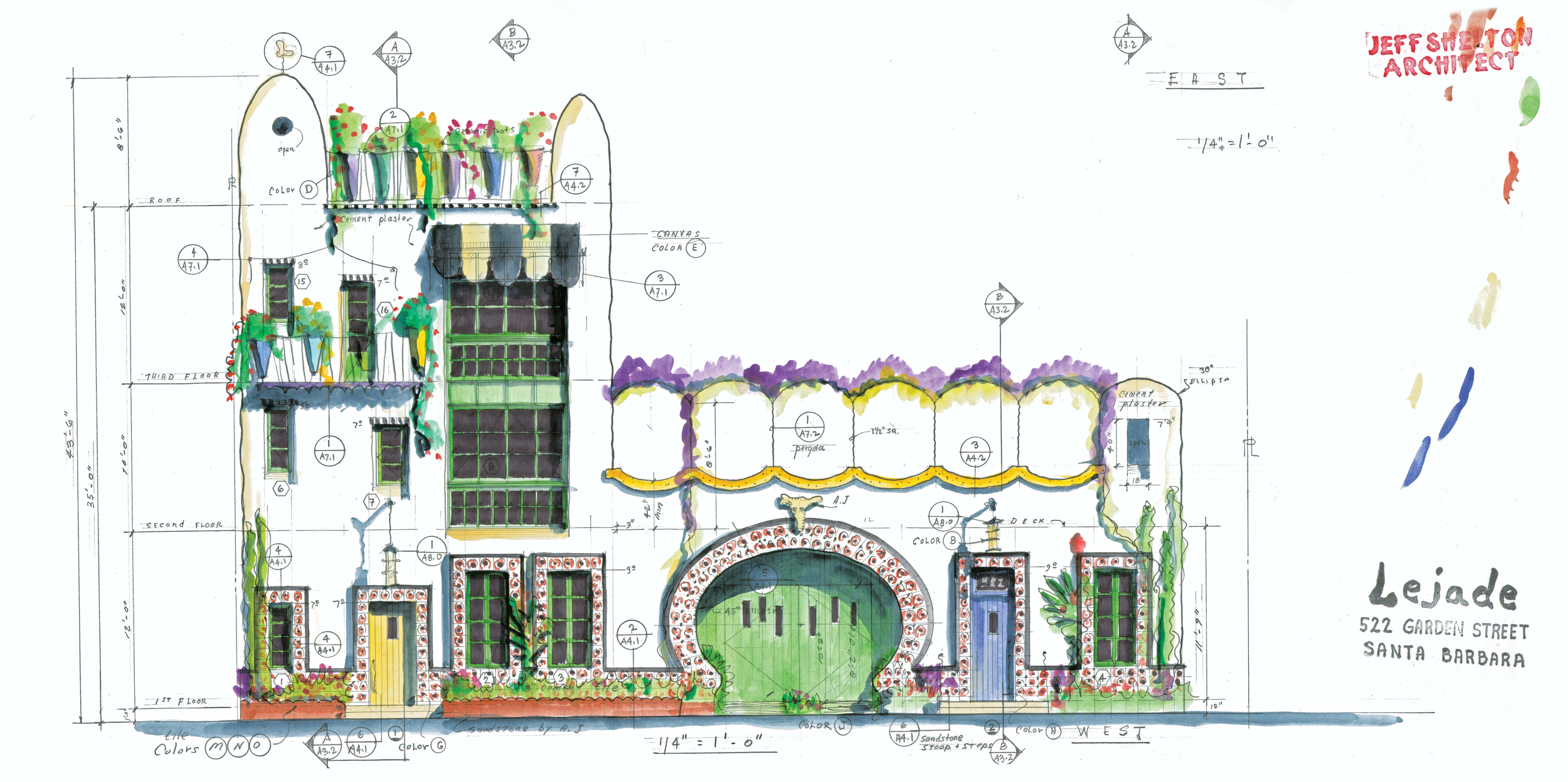

Shelton Style

The architect creates his signature works with dazzling craftsmanship, flair, and imagination

The Architect creates his signature works with dazzling craftsmanship, flair, and imagination

Text and images excerpted from The Fig District: Some Buildings in Downtown Santa Barbara (Fig Press) by Jeff Shelton with photography by Jason Rick

The Fig District is a figment. There is no Fig District. That is, unless your office is on Fig Avenue, and you have been lucky enough to have designed eight buildings within six blocks of your drawing desk.

A city would never name a district after this glorified alley. Fig Ave is an endearingly derelict one-block street in downtown Santa Barbara, behind a handful of State Street’s bars and restaurants. By day, beer kegs are unloaded from delivery trucks, denting the asphalt with friendly smiles and making sounds like hammers hitting an anvil, and at night, intoxicated revelers regurgitate maps on the sidewalk after having had too much to drink.

My office has been on “Fig” for twenty-three years. For fifteen of those years, my brother David’s ironwork shop was one hundred steps from my office door, in the old Hendry Brother’s Steel Shop on the corner. One hundred steps in another direction is the James Joyce pub, where we made our conference table for afternoon meetings. Having designed two buildings only a Frisbee throw from the office, and six more within six blocks, we at some point began referring to this zone as “The Fig District.” Buildings I design within this district tend to get an extraordinary amount of my attention, as daily walks to the coffee shop inevitably lead to job site visits.

The buildings in this zone are architecturally related as most of them sit within Santa Barbara’s Historic Landmarks District, or “El Pueblo Viejo,” as the City refers to it. This design district was created after an earthquake in 1925 destroyed many buildings in Santa Barbara, and it requires buildings to conform in some odd way to design standards based on the historic influences of Andalucia and Southern Spain. Essentially, the buildings need to incorporate plaster, ceramic tile, terra cotta tile, and ironwork, using building proportions that mimic stone or adobe construction. Design Review Committees carefully scrutinize projects in this area to make sure they’re sympathetic to the City’s strict guidelines.

I designed each building to maintain an inherent pedestrian orientation and to be sensitive to the community as a whole.

When I moved back to Santa Barbara, I hadn’t worked with plaster on any projects in my early career as an architect. I had worked mostly with steel, glass and concrete block. To begin to understand what this “Spanish thing” was about, I found books with photos of cities and buildings in Spain, and realized the beauty and opportunity that existed in the malleability of plaster.

In 2000, I started designing the Pistachio House, which was the first of my eight projects in The Fig District. Since these buildings are downtown, I designed each to maintain an inherent pedestrian orientation, to react to its neighboring structures and to be sensitive to the community as a whole. Seven of these projects were built by Dan Upton and his crew of talented builders, and my brother, sculptor/ metalworker David Shelton, designed and brought the ambitious ironwork to life on all eight.

All of the people who have worked on the Fig District projects have grown to understand that it is the building, not the architect, that begins to make the design choices.

The same freewheeling, independent band of local artisans and craftspeople have added an extra layer of life to all of these buildings and at each location, you’ll find their names listed on ceramic tile plaques. Though the idea of working with a guild is from another time, we have somehow found ourselves in the middle of one, full of people with similar goals and dedication to their craft. We use the term loosely, perhaps romantically, throwing out any cumbersome archaic politics but keeping the interesting and productive ideas of a guild.

A stroke of good fortune for the buildings in the Fig District, as well as the other buildings I’ve designed, is that we have somehow been united with great clients willing to jump into our world and let a project organically grow from logic and delight. There is an uncommon amount of trust and faith required in this process and for a time, the Guild will be part of the client’s life. One client once described the job site experience this way: “First there is the rough grading, and then the Merry Band of Artisans shows up.” Our job sites are always joyful, even on the bad days.

Our intention is always to give life to the street and to create a building that invites and brings delight to the pedestrian and the community. The construction of a building should be an enjoyable event.

When prospective clients come into the office, I first try to scare them off. Some leave right away, perhaps in astonishment, wondering how anyone would want to jump onto a seemingly unruly bus rambling down a narrow mountain road with the seats already full of the Merry Band of Artisans and all of their family members, only to be asked to close their eyes and have faith that the journey and the outcome will be a success.

Over the years, new workers, artists and craftspeople filter into our odd building process, while others move on or retire. One thing is clear; all of the people who have worked on the Fig District projects have grown to understand that as each building emerges out of the ground, it is the building, not necessarily the architect, that begins to make the design choices and we all need to show up and listen to it every day. Sometimes the stars line up and sometimes we need to draw a curvy line to get them to align, then squint and pretend that they’re lined up exactly how we want them to be. Whatever the means, creating a building requires the imagination, perseverance and cooperation of a lot of people who want to go in a similar direction, who are not confined by restraints and norms that seem to stifle thought and keep us from taking big breaths of life.

Buildings are designed with pencils and pens on vellum and tracing paper, and the designs reflect the relationship of a hand-drawn line interpreted by hands in the field. The people building these buildings appreciate the care that goes into the plans and so in turn put in the same amount of thought when they show up each morning to work. Everyone has the desire for beauty and delight, and that sometimes takes a fight and sacrifice to achieve.

Meanwhile, I fiddle with my pencil as I wait for the next Fig District client to knock at my door.

See the story in our digital magazine

Chicana Cultura

An urban tour of the Eastside and Milpas corridor—taste, see, and learn what makes this side of the neighborhood and its people so special

An urban tour of the Eastside and Milpas corridor—taste, see, and learn what makes this side of the neighborhood and its people so special

Written by Michael Montenegro | Photography by Sara Prince and Dewey Nicks

CRUISING

George Trujillo’s family business—his barber shop—was established in 1929. It’s like going down memory lane, with the original vintage barber sign and black-and-white checkered floor. Brothers Efrem Reynozo (in the 1957 Chevrolet Bel Air convertible in Inca Silver) and Rene Perez (in the 1958 Chevrolet Impala in Blue Magic) cruise the backside of Ortega Park. If you are lucky, you could soon take a tour of the American Riviera in style too—Reynozo will be launching a vintage-car tour service in 2022.

TASTE CALLE MILPAS

The iconic La Super-Rica Taqueria that Julia Child called one of her favorites. Owner Isidoro Gonzalez’s tacos and tamales still draw crowds lining up around the block, and he only takes cash. Do as locals do to get the morning started with pan dulce or a breakfast burrito at La Tapatia Bakery. Craving seafood and Mexican food? Look no further than Cesar’s Place; the michelada is a must-try too.

FIESTA

It’s not a party without a piñata. The tradition has Mesoamerican Native roots and has been practiced in our community for over a century. Find these colorful favors—which were originally made of clay—at local stores or visit Chapala Market (shown here), one of the best-stocked and most-frequented tiendas on Milpas.

Ortega Park is the heart of Santa Barbara. The vibrant murals tell the stories that represent our diverse community. If only this piece of land could talk—its memories would span from being a salt marsh to a town dump to the creation of the historic park in the 1920s. Decades of celebrations have taken place here, like Cinco de Mayo festivals with lowriders, quinceañeras, and block parties. It’s the people—the children, parents, and elders from the neighborhood over the generations—that make the park special. Ortega Park was intersectional because of the multiculturalism of African, Italian, and Irish people, alongside those of Mexican heritage. Generations migrated here to pursue the American dream for a better future for their children.

MENTORS

Superior Brake and Alignment owner Bob Seagoe services classic cars and gives back to local youth by offering mechanics apprenticeships, since many of these technical classes have been cut from local high school budgets; El Potrillo Western Wear carries Mexico’s finest boots and clothing and offers discounts for local charity and school fundraisers; Bobby Bisquera, aka Mexipino, in his 1961 Chevy Impala convertible; Efrem Reynozo; crafts from Mujeres Market; Danny Trejo, president of Nite Life, the longest running automobile/lowrider car club in Santa Barbara.

Think of locals dancing to cumbia and decompressing to Mexican ranchera music.

NIGHT LIFE

La Pachanga Night Club unfortunately is not active anymore, but it once was the place to be: It was loud and carnival-like and felt like a hometown dive bar or cantina that would encapsulate you somewhere in the Southwest or Mexico. It was a place where English was spoken as a second language, with a Latin accent.

Raze Up hits the streets; Ruben Perez in a 1957 Chevy Impala in Blue Magic; in the summer of ’75, neighborhood children immortalized themselves in concrete during the completion of Ortega Park; Trejo’s 1952 Chevy Suburban; Michael Montenegro, writer and filmmaker (@ChicanoCultureSB). Jorge Salgado, owner of the Barber Shop, and his 1950 Mercury; Cindy Falcon, a legendary Chumash Chicana, was the president of Ladies United, an all-women lowrider/automobile club during the 1970s; Augie Trejo in his 1950 Chevrolet Deluxe; Art Perez’s 1939 Chevrolet coupe.

THE FUTURE

Beauty with resilience runs in the Jaimes family: Valerie, younger sisters Lilyanna and Alicia, and mother Charlotte. Valerie, a community organizer and activist, was born and raised in Santa Barbara, is an alumna of Santa Barbara High School, and recently graduated from the University of San Diego—the first member of her family to graduate from college—with a bachelor’s degree in ethnic studies and sociology. “Higher education has empowered me to be who I am,” she says. “My future is to be an educator and empower my community to be who they want to be, whether they want to learn a trade, be an artist, or explore outer space.” Valerie is currently residing on Kumeyaay indigenous land and working with the Chicano Park Museum and Cultural Center in San Diego.

See the story in our digital magazine

On Kyle’s Pond

A Native New Yorker finds Art in Nature

A Native New Yorker Finds Art in Nature

Kyle DeWoody afloat in the natural swimming pond at her Central Coast ranch.

Written by L.D. Porter | Photographs by Sam Frost

She’s been at the center of the art world for most of her life. But for the past five years, Kyle DeWoody has spent much of her time in rural Ventura County, navigating a Kubota utility vehicle over uneven terrain to see how her avocado, banana, and mango trees are faring. This may shock those familiar with her undeniably glamorous image, featured in Vogue, Vanity Fair, and W magazine, and on countless art blogs. But close companions know it’s simply another interesting curve in the New York native’s fascinating life trajectory.

Let’s start with genetics. Her father, James DeWoody, is a renowned artist whose work resides in many private and public collections, including New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her mother, Beth Rudin DeWoody, is a philanthropist, arts patron, and curator, known for championing overlooked artists. Given that pedigree, DeWoody says, “I had no chance of escaping the art world.”

In fact, the art world came to her. “It was obviously an incredible treat to grow up around not only amazing art but amazing artists,” she says, adding, “most of my parents’ close friends were artists or curators.” Art history was her chosen topic at Washington University in St. Louis, and her real-world experience was honed by stints at the Whitney Museum and Creative Time, a nonprofit institution that commissions public art projects.

She co-founded the e-commerce site Grey Area in 2011, with unique editions of art, jewelry, and objets; it ultimately expanded to include pop-up installations combining art exhibitions with art-related merchandise in tony locales like the Hamptons, Miami, and Los Angeles. Soon DeWoody became a go-to advisor for boutique hotels and brands seeking to create special environments with art. In other words, she’s a major influencer and tastemaker.

But success can exact a toll, and for DeWoody that amounted to a series of chronic health issues that demanded attention. The path to healing pointed to Los Angeles, where her brother Carlton had decamped a couple years earlier and her mother had established a pied-à-terre with husband Firooz Zahedi, a noted photographer. (L.A.’s stellar art scene likely sealed the deal.) DeWoody embarked on a program of self-care with health-care practitioners and holistic treatments including integrative stretching (a form of fascial release to repair structural and physiological issues) and dietary changes to eliminate inflammatory foods. The healing process fueled her desire to connect with the land in a direct way, a desire that was fulfilled when she discovered a sprawling ranch—formerly a walnut farm—in a lush valley between Carpinteria and Ojai.

From the moment she walked onto the property, DeWoody could sense that a natural pond would fit perfectly in the landscape. Used throughout Europe, eco-swimming pools eschew chemicals, using plants to filter the water. Although the concept is just starting to catch on stateside, DeWoody is a quintessential early adopter. She designed the pond’s configuration, and David Cameron helped put the final touches on the landscaping. “It’s an evolving technology and not for everyone,” she admits, “but it feels so good, and it’s incredible to swim next to lotuses and grasses.”

The pond is in plain view of a tiny ranch house DeWoody has lovingly refurbished with wood salvaged from fallen walnut trees on-site, the unfortunate victims of California’s now-pervasive drought. Hence the lovely walnut countertops, ceiling-beam edging, and custom furniture gracing her small abode, all achieved with the assistance of talented designer Case Fleher. As of now, roughly 5 of the ranch’s 65 acres are landscaped; the remaining acreage has been cleared for fire protection (thanks to seasoned caretaker Paco Alexander) but otherwise left to grow wild.

Of course, even in this bucolic setting, art and activism are never far from DeWoody’s mind. Before COVID, she curated projects like “My Kid Could Do That,” a recurring fund-raiser featuring childhood artwork of prominent artists (think Ed Ruscha and Catherine Opie) to provide free arts programming for children, and supported fund-raising efforts for L.A.-based Habits of Waste, a nonprofit whose goal is to activate simple behavioral changes to reap a powerful impact, like banning single-use straws and cutlery. “All the things we take for granted are no longer a given,” DeWoody notes: “how we treat each other, how we feed ourselves, how we ensure a future for our children. Everything needs to be fought for in a certain way.”

Along with her romantic partner Samuel Camburn, a screenwriter and actor, DeWoody recently hosted a group of artists affiliated with the Ojai Institute, an initiative of Ojai’s Carolyn Glasoe Bailey Foundation, gathered by the foundation’s executive director, Frederick Janka. Under spreading olive trees, they dined on a magnificent plant-focused feast prepared by chef Loria Stern. Ezra Woods of L.A.’s Pretend Plants & Flowers and artist Samantha Thomas foraged foliage to garnish the lavishly appointed table. Noted ceramist Yassi Mazandi brought along her handmade shot glasses (perfect for tequila quaffing), and artist Ry Rocklen added his Pixie ceramic sculptures.

DeWoody credits her involvement with the land as a key to her improved physical well-being. It’s also no surprise that the prospect of a pristine landscape would naturally whet her appetite for curating art installations, and that’s exactly what’s up next. The rest of the beautiful felled walnut wood will be distributed to artists to create pieces for a future art installation. The art world is indeed DeWoody’s world.

“All the things we take for granted are no longer a given: how we treat each other, how we feed ourselves, how we ensure a future for our children. Everything needs to be fought for in a certain way.”

See the story in our digital magazine

Keaton, Au Courant

The star and executive producer of Dopesick shares some thoughts on impactful movies, Santa Barbara, and the importance of the arts

The star and executive producer of DOPESICK shares some thoughts on impactful movies, Santa Barbara, and the importance of the arts

Interview by Roger Durling | Photographs by Dewey Nicks

In 2001 I owned a coffee shop in Summerland, California, and Michael Keaton would frequent it. When he first introduced himself to me, wearing a baseball cap, he simply said his name was Michael. But that voice I’d heard in Mr. Mom and Beetlejuice was easily recognized, and the lips that were accentuated by the mask he wore for his iconic take on Batman instantly gave him away. We struck up a friendship based on our curiosity for movies, and we would have conversations about up-and-coming Mexican filmmakers like Alfonso Cuarón and Alejandro González Iñárritu. Little did we know that he would go on to star in the latter’s Birdman or that the film would mark one of the greatest comebacks in Hollywood history. For two decades Keaton and I have kept in touch. He’s continued to ride this new rewarding artistic phase of his career with challenging work, including starring in and executive producing a Hulu series called Dopesick, which may be his finest performance to date. He’s one of the best actors working today.

Recently, we sat down to converse once again, over lunch at the El Encanto hotel.

Dopesick is an amazing series.

I just watched myself, and this is the first thing I’ve watched of mine in many years; I don’t like to watch myself. I lost a nephew to fentanyl and heroin. So I wanted to watch to make sure we did it right.

I don’t remember a TV series with so many flashbacks. Did you shoot it chronologically?

I was already committed to doing another film in the UK, and I had to be there by a certain time. And I was in a crunch in terms of when I could do Dopesick. Therefore there was almost no shooting in any chronological time for me. At some point I just gave in to the thing.

Did the things that you learned from shooting Clean and Sober help you with this?

It was a huge advantage. And then I thought to myself, Wait, am I just being lazy? And that’s a distinct possibility. But what I learned from the research during that movie helped enormously.

Why don’t you like seeing yourself in movies?

I don’t know. I’m self-critical, and I’m not really that interested. I want to move on to the next thing.

Keaton keeps under the radar locally—enjoying foggy beaches in the winter and time with his horses.

Is there one movie that you’re particularly proud of?

Well, because Birdman and Beetlejuice are so truly original—and I don’t throw the word “art” around a lot—I’m proud of those two for sure. I always like to give art people—actors, directors, writers, painters, anybody in the art world—a ton of points for courage, for risking, for being willing to fail and fall. I would, off the top of my head, say those two for those reasons. Multiplicity is really underrated because of the degree of difficulty. I’m sure there are others. But to make Multiplicity now would be technologically much easier. It was so much fun to try to figure out and do.

After Birdman, you went on to do Spotlight, The Founder, The Trial of the Chicago 7, Worth, and now Dopesick. And they’re all questioning and talking about American issues, social-justice issues. Is that a conscious thing?

I grew up in a house where my parents would discuss things. Sometimes not even on an intellectual level. There was just discussion. My dad was involved in local politics. I was excited when I became 18 because that was the first year I could vote. That was huge. So it’s always been there, and I’m always watching news and reading newspapers, and I stayed conscious. There were years where I was less involved, but I’m probably more a product of my generation than anything else.

“I’m extremely fortunate, honestly, to have a job that I really like, that might possibly have an impact on people.”

Being in a movie like Spotlight, you put a face to abuse by priests.

I was also an altar boy and a devout Catholic for a long time.

And by being in Dopesick, you put a face to addiction, to OxyContin.

Yep. And Clean and Sober.

And shedding light on 9/11 in Worth.

And what I did in My Life, I always thought it pretty good. It may not be brilliant, but if this all falls apart tomorrow and I don’t ever get hired again, I’ll have something in the world that may help somebody. I’m extremely fortunate, honestly, to have a job that I really like, that might possibly have an impact on people.

“I always like to give art people—actors, directors, writers, painters, anybody in the art world—a ton of points for courage, for risking, for being willing to fail and fall.” Jacket courtesy of Brunello Cucinelli, Rosewood Miramar.

This career renaissance that you’re in right now, how do you feel about it?

It’s fun! And I do get how it’s called a renaissance. And I honestly did get how people referred to Birdman as a comeback. I’m OK with it. To me, it’s just me going to work. I’m just doing what I’ve really always done. Have I turned up the volume a little? Yeah, for sure. And I think some of it is because I like it more than I have for a long time.

You were always popular, and people adore your doing blockbusters and popular comedies, but after Birdman, now you’re like an American Laurence Olivier.

Hold on now.

You’re like this very serious actor.

That’s nice, and I think at some point, if I step back and look at things, I wouldn’t be shocked if people say, “Hey, Mike, thank you, and with all due respect, you’re a serious dude. Now do us a favor, lighten the fuck up for a while.”

I don’t think you’re going to have that problem.

Well, it’s just so much fun to do comedy. I miss it so much. And when I work on it, I’m really, really diligent about it. I admire it so much when I see it done well.

“Have I turned up the volume a little? Yeah, for sure. And I think some of it is because I like it more than I have for a long time.”

When did you first come to Santa Barbara?

The very first time I came to Santa Barbara was in the late ’70s. Me and a couple of pals drove my ’63 VW Bug up here, and we slept on the beach. It was cool. And remember how horsey it was then? But horsey in the coolest way. There would be horses walking along the streets, right through town.

Even 20 years ago when I met you.

One of the most impressive things I find up here is the Montecito trail system. I’m amazed that they continue to keep it going. When I first came here, I didn’t have any money. I may have had $280 when I came to California. So my brother loaned me some money, and I bought a car for $700 and came up here. I thought, What a beautiful place. And I remember the light, and I went, Wow, this light is really special. And I thought if ever I could afford a second place, maybe this would be a fun place. I’ve had a few places here and there and kind of kept it under the radar.

Keaton discovered Santa Barbara in the late ’70s by driving up with some pals and sleeping on the beach. Now he enjoys the easiness of strolling the Summerland streets.1969 Barracuda convertible courtesy of Jill Johnson/Loveworn.

What does Santa Barbara represent to you? In your interviews you mention Montana and keep Santa Barbara out. Is it intentional?

I’m a California fan, actually. First of all, physically, it’s really pleasant here in Santa Barbara, and it’s a great place to just get out for a minute. I love the beach in the winter, and there’s not many people around on the beach in the winter. I love that this morning the fog was so stunningly beautiful. The changes in the climate are great. And then once I could move my horses here, it became even better.

And people leave you alone.

Yeah, the people are totally cool. But since I’ve been small, I’ve always been very aware and sensitive to my physical surroundings—like scale and light and space. I think there’s just a ton of really interesting people here: T.C. Boyle and others.

You know what I find as I get older? I get more excited about true creativity or art. Thomas McGuane is a good friend of mine. I was just reading one of his pieces in The New Yorker. I read it, and I went, Man, there’s a couple of phrases.… Like when you read something great, you have to set the book down and go, I just have to think about what I just read. Or when you see a true painter or an original painting. Don’t you find that the longer you live, you actually get more excited about that? And I don’t know if that’s a question of me going, I don’t have that much time, I’ve got to savor all of this. I don’t know what it is, but I get excited about anything creative or artistic or anything having to do with art. It’s thinking, Am I ever going to really get them? To really get it?

See the story in our digital magazine

A Passionate Pursuit

Collectors Sandi and Bill Nicholson celebrate women who make art

MARTHA GRAHAM 25, 1931, photograph, 12 x 17 in. Imogen Cunningham (1883-1976).

Collectors Sandi and Bill Nicholson celebrate women who make art

Written by L.D. Porter | Photography courtesy of Women Who Dared

Like most art collectors, the Nicholsons—Sandi and Bill—are interesting people. What makes them fascinating is the nature of their collection: All of the work is by women artists.

Twenty years ago, the couple—whose Montecito pied-à-terre is the historic Villa Solana—traveled across Europe and was shocked to discover that none of the many museums they visited featured art by women. “That’s what started it,” says Bill, “the curiosity of why women weren’t represented.” Since that time, the Nicholsons’ curiosity has led them to acquire 340 works—dating from 500 B.C. to the present—featuring female artists from all seven continents. Aptly named Women Who Dared, theirs is the largest privately held collection of its kind in the world.

“As we were putting the collection together, we realized that we really wanted to show the diversity of women,” explains Sandi. “We wanted to show art by women over time and through geography—internationally and throughout the ages.” The two traveled the world seeking art by women. They even went as far as Antarctica, where they acquired the work of contemporary photographer Zenobia Evans, who is a scientist living and working there. Sandi sums it up: “We love art, and we love collecting, and we love travel. And through this, we discovered artists whose voices had been suppressed or never heard. Now as the Women Who Dared collection, it’s become the chorus of global voices over more than 2,500 years.”

The Nicholsons became familiar with the myriad obstacles facing women artists, especially those born before the 20th century. “Women were treated almost as witches or adulteresses,” says Bill. “Men really worked hard to keep them out of the art establishment.” Jeremy Tessmer, of Santa Barbara’s Sullivan Goss—An American Gallery, observes that when the Nicholsons began forming their collection, artworks by women “were buried by time and the functional indifference of the art establishment.” The couple discovered that female artists who did receive support and encouragement were often married to an artist or worked as an artist’s assistant. Sandi notes that if women were given the opportunity to study and paint, “that became evident in the exposure of their works.”

Italian-born Ely De Vescovi (1910-1998) assisted Diego Rivera with several murals, and her discovery of modern fresco techniques in the 1930s was heralded by none other than The New York Times. De Vescovi moved to California in the 1940s and completed four mural panels in the acute mental wards of Los Angeles’s Sawtelle Psychiatric Hospital. She thereafter fell into obscurity until the late 1990s, when her nephew, the late gallery owner Robin Bagier of Ojai, exhibited her prolific and varied work. The Nicholsons own several pieces by De Vescovi, and Bill believes the artist’s later works—which became increasingly spiritual and visionary—resulted from her work at a veteran’s hospital with American soldiers returning from World War II.

Sandi especially loves the regal oil portrait of an African-American woman—simply titled Florence—by Lyla Vivian Marshall Harcoff (1883-1956). “That painting is very important,” says Sandi. “It shows pride, it shows dignity, it shows courage. During the Depression, Lyla—in order to financially survive—established herself as a furniture maker, which led to her making her own frames for the rest of her life.” Born in Indiana, Harcoff graduated from Purdue University in 1904 (one of eight women in a class of 218) and studied in Paris. She eventually moved to Santa Barbara, where she commissioned architect Lutah Maria Riggs to convert a carriage house into her studio/residence. The Santa Barbara Museum of Art gave her a solo show in 1949, and she was widely exhibited during her lifetime. Harcoff also completed several murals for the Works Progress Administration, including a mural at Santa Ynez Valley High School in 1936.

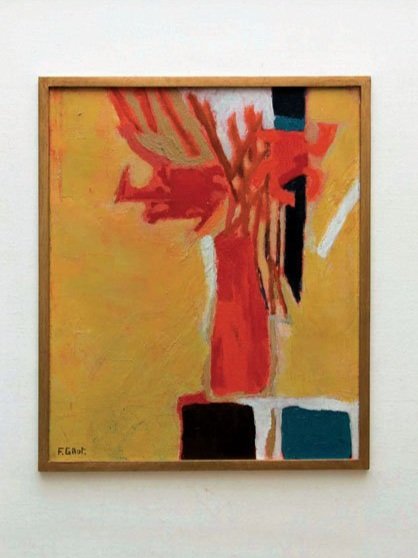

French-born Françoise Gilot (b. 1921) was an artist in her own right when she met Pablo Picasso, with whom she had a turbulent 10-year relationship. After their relationship ended, Picasso instructed all the art dealers he knew not to buy Gilot’s art. The Nicholsons acquired Gilot’s Flowers on a Yellow Field—a brightly colored, almost abstract oil painting for the collection; it is a dynamic example of the artist’s unique talent, as well as evidence of her determination. The Nicholsons have been in contact with Gilot (now 97), and hope to have a face-to-face meeting with the artist who defied Picasso.

The Nicholsons’ curiosity has led them to collect 340 works—dating from 500 B.C. to the present—featuring female artists from all seven continents.

Photography is a strong part of the collection, and American photographer Imogen Cunningham (1883-1976) is one of the standouts. An Oregon native, Cunningham was a contemporary of several noted male photographers who championed her work—Edward S. Curtis (for whom she worked), Edward Weston (who helped exhibit her work), and Ansel Adams (who invited her to join the faculty of the California School of Fine Arts). Cunningham’s photographs were published in Vanity Fair, where she worked from 1934 to 1936. Even so, the major awards she received—fellowship in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and a Guggenheim Fellowship—were granted in the last decade of her life. “Imogen Cunningham was really ahead of her time,” says Bill. “It is just within the last 10 years that photography by women has become recognized and appreciated in the market financially.” The collection’s luminous black-and-white portrait of modern dancer Martha Graham comes from a photo shoot that occurred on a hot afternoon in Santa Barbara. Graham—who spent her teenage years in Santa Barbara—met the photographer at a dinner party, and the photos were taken in front of Graham’s mother’s barn. Cunningham was 48, Graham was 37.

Among the collection’s abstract works is a striking geometric oil painting by Russian artist Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962). An active member of several avant-garde movements, Goncharova’s first major solo exhibition debuted in 1913. Moving to Paris in 1914, she produced costumes and set designs for Sergei Diaghilev’s famous Ballet Russes. She was included in the groundbreaking 1936 “Cubism and Abstract Art” show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and the museum has her work in its collection to this day. As evidence of her continuing importance in the art world, London’s Tate Modern museum mounted a Goncharova retrospective this year.

“As we were putting the collection together, we realized that we really wanted to show the diversity of women. We wanted to show art by women over time and through geography—internationally and throughout the ages.”

For the Nicholsons, every work in the collection has an important backstory to tell. As Sandi says, “We were first attracted to the artwork but soon realized the story or the narrative of the artist’s work and their lives resonated with us in a profound way. The artist’s perseverance, grit, and determination have been as powerful to us as the work itself.”

Understandably, the couple’s ultimate goal is to keep the collection together in an institution where “the girls” (as Sandi fondly calls them) can impact a large number of people on a regular basis. Bill adds, “We’d like to have people free to interact with the collection and hear the stories.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

Living with the Artists

A peek inside Jacquelyn Klein-Brown's contemporary art haven

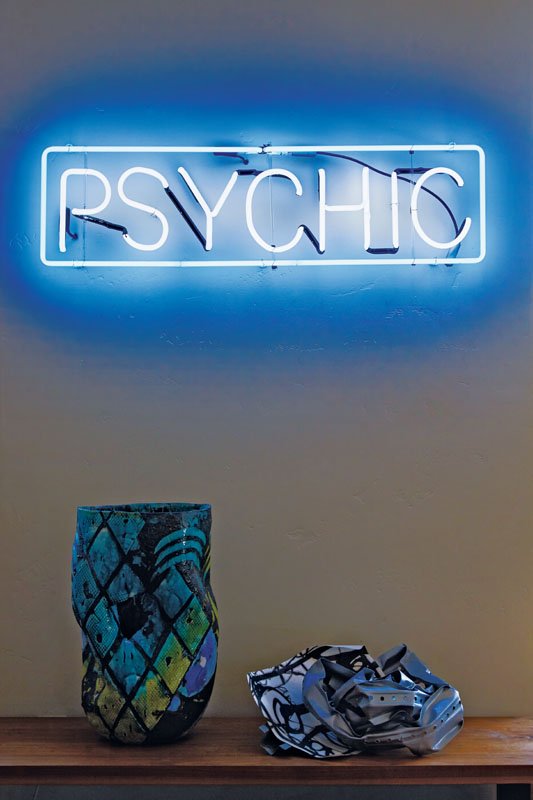

The outsized installations of arts collective Assume Vivid Astro Focus pack a vivid punch in a narrow corridor.

A peek inside Jacquelyn Klein-Brown's contemporary art haven

Written by Ninette Paloma | Photographs by Sam Frost

Stroll toward the entrance of Jacquelyn Klein-Brown’s inviting Montecito estate, and you’ll be greeted by artist Hayal Pozanti’s shimmering steel sculpture, its assertive curves and angles guiding you toward the front door. Inside, Anicka Yi’s seductive orchids and Marilyn Minter’s intrepid photography cut a striking image against midcentury modern furnishings—their lines and metaphors shifting with the afternoon sun. At every turn, the eye is pulled toward saturated canvases and outsize textiles, a sensorial playground of color and imagery with the petite and vivacious Klein-Brown at its epicenter.

“Most of the art in my house stimulates thoughts and emotions, often igniting happy, somber, or provocative feelings.” Klein-Brown explains with a laugh. “Depending on the time of day, you can see each piece in a different light. Sometimes I feel they’re a direct reflection of my mood—always speaking to me in a new way.”

Communicating with her sprawling collection is a daily occurrence for Klein-Brown; with paintings, photographs, sculptures, videos, and ceramics assembled throughout her home, the exchanges can feel boundless. “I can sit for hours with friends over a glass of wine contemplating the meaning of a photograph or installation,” she muses. “We’ve had some pretty incredible conversations in this house.”

For as long as she can remember, Klein-Brown has been contextualizing her world through the lens of contemporary art, inspired by her family’s unyielding passion for the avant-garde and emerging. As a young girl growing up in Houston, she would accompany her parents on art expeditions, shuffling between museums and galleries and attending notable exhibit openings across the globe. At the University of Texas at Austin, she majored in art history and slowly began to acquire a modest collection of her own, joining museum groups, exploring galleries, becoming acquainted with curators, and participating in artist talks wherever she traveled. By the time she moved to Santa Barbara in 2006, her life’s trajectory had become clear. “I had two priorities when I moved here,” she recalls. “Enroll the kids in a great school and join every art museum in town.”

Both the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara (MCASB) and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art came answering, offering Klein-Brown formidable seats on their respective boards. Through dedication and an extensive network of industry connections, Klein-Brown began earning a reputation as a trusted source for encouraging support and awareness in the visual arts—a role she approaches with a healthy balance of passion and pragmatism. “To work with someone who cultivates such a sense of fairness where everyone’s voice can be heard is a tremendous privilege,” says Abaseh Mirvali, former Executive Director of MCASB. “Jacquelyn fosters an environment of authentic generosity and she’s the first to lead with a giving spirit.”

On any given week, Klein-Brown makes it a point to open her home to art students and educational groups, offering insight and intimate anecdotes over the artists that live among her. Her face lights up as she recalls each moment of discovery—when a trip to an art fair led to an encounter with an artist that soon became a lifelong friend, or the feeling that bubbles over when she connects with a piece at first glance. “Every work that I’ve brought into my home feels very personal to me,” she explains. “I hope I am building a legacy that’ll last longer than any of us.” But refer to Klein-Brown as an avid collector, and she’ll be the first to point out that her egalitarian view of art aligns closely with her commitment to its social implications.

“I don't like using the word ‘collector,’” she stresses. “I feel like I’m just a host for the work and it’s a privilege to have them for the time they’re with me. My curiosity lies in how art can be used to build stronger communities or as a vessel for social justice. I’m collecting ideas on how to work toward that.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

Big Shot

If an image of Jim Morrison, The Rolling Stones, Simon & Garfunkel, The Mamas and the Papas, The Beach Boys, or The Byrds has been burnished into your memory, chances are you’ve been touched by the work of Guy Webster

If an image of Jim Morrison, The Rolling Stones, Simon & Garfunkel, The Mamas and the Papas, The Beach Boys, or The Byrds has been burnished into your memory, chances are you’ve been touched by the work of Guy Webster

Written by Katherine Stewart | Photography by Guy Webster

Perhaps the most influential visual chronicler of the great age of classic rock, Guy Webster shot album covers for dozens of bands as well as portraits of prominent cultural figures including Dennis Hopper, Jane Fonda, Ravi Shankar, Jack Nicholson, Eva Gabor, Truman Capote, Judy Collins, Rock Hudson, Janis Joplin, Barbra Streisand, Mick Jagger, and presidents Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton.

During the Nixon administration, Webster decamped from California, where he was raised, to Italy and Spain, returning after a half dozen years. He met and married his wife Leone, and they moved to a restored farmhouse in Ojai, where they raised daughters Merry and Jessie, enjoying visits with Sarah, Michael, and Erin—Webster’s children from his first marriage. In 2019, at age 79, Webster died of a longstanding illness. We chatted with his daughter Merry to learn more about the man behind the legend.

How did your father manage to capture the iconic images he produced?

My father obtained a master’s degree in art history at the University of Florence and used his understanding of light and composition from classical paintings in his own photography.

A majority of the artists he photographed were living the high life of the ’60s and ’70s. Many were experimenting with drugs, and they often needed wrangling. At the time my father shot the iconic bathtub cover of The Mamas and the Papas album If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears, the band was hanging out in a house in Laurel Canyon. There was a large bowl of weed burning in the middle of the living room, and no one had the stamina to go outside to shoot the album cover. So my father told them to get in the bathtub and just had them relax there while he took the photos.

What are some things that few people know about your father?

My father was an epic storyteller. He would find a corner seat at a party and let people come to him. By the end of the night, you could always find him holding court to a large group enchanted by his

life stories.

His father, Paul Francis Webster, was an award-winning lyricist who won three Oscars and a Grammy and was nominated for 14 Academy Awards. So music was a big part of my father’s upbringing. He was influenced by everything from opera to early folk to 1970s rock and would test my sister and me on names of blues and opera singers during our daily carpool.

“He credited Bob Dylan with orienting his life toward social justice, and he loved the values the ’60s brought to society.”

What type of music did he enjoy listening to at home?

In his early teens, he had a serious injury to both his hands. To ease his boredom while recuperating, he began listening to opera on his radio—this began his lifelong love and study of the genre.

In his studio, in the car, and at home, he loved listening to the blues, opera, and classic folk music—and he often returned to Van Morrison, who was a favorite. He credited Bob Dylan with orienting his life toward social justice, and he loved the values the ’60s brought to society. He also regularly listened to the artists he worked with, since many of them were his close friends.

How did he relate to you and your sister as children?

My father wasn’t a traditional “father figure” in that he didn’t check up on our grades, enforce bedtime, or reprimand us. My mom, Leone, was the person who looked after us in those ways. He did teach us a lot about culture, history, music, and classic movies though. He wasn’t shy about regaling us with his irreverent adventures and subsequent life lessons.

He also volunteered to teach photography at our school (The Oak Grove School in Ojai) so we could learn about the darkroom and understand lighting and composition. He was instrumental in inspiring many of his students to pursue photography careers.

Tell us about his passion for motorcycling.