A Passionate Pursuit

MARTHA GRAHAM 25, 1931, photograph, 12 x 17 in. Imogen Cunningham (1883-1976).

Collectors Sandi and Bill Nicholson celebrate women who make art

Written by L.D. Porter | Photography courtesy of Women Who Dared

Like most art collectors, the Nicholsons—Sandi and Bill—are interesting people. What makes them fascinating is the nature of their collection: All of the work is by women artists.

Twenty years ago, the couple—whose Montecito pied-à-terre is the historic Villa Solana—traveled across Europe and was shocked to discover that none of the many museums they visited featured art by women. “That’s what started it,” says Bill, “the curiosity of why women weren’t represented.” Since that time, the Nicholsons’ curiosity has led them to acquire 340 works—dating from 500 B.C. to the present—featuring female artists from all seven continents. Aptly named Women Who Dared, theirs is the largest privately held collection of its kind in the world.

“As we were putting the collection together, we realized that we really wanted to show the diversity of women,” explains Sandi. “We wanted to show art by women over time and through geography—internationally and throughout the ages.” The two traveled the world seeking art by women. They even went as far as Antarctica, where they acquired the work of contemporary photographer Zenobia Evans, who is a scientist living and working there. Sandi sums it up: “We love art, and we love collecting, and we love travel. And through this, we discovered artists whose voices had been suppressed or never heard. Now as the Women Who Dared collection, it’s become the chorus of global voices over more than 2,500 years.”

The Nicholsons became familiar with the myriad obstacles facing women artists, especially those born before the 20th century. “Women were treated almost as witches or adulteresses,” says Bill. “Men really worked hard to keep them out of the art establishment.” Jeremy Tessmer, of Santa Barbara’s Sullivan Goss—An American Gallery, observes that when the Nicholsons began forming their collection, artworks by women “were buried by time and the functional indifference of the art establishment.” The couple discovered that female artists who did receive support and encouragement were often married to an artist or worked as an artist’s assistant. Sandi notes that if women were given the opportunity to study and paint, “that became evident in the exposure of their works.”

Italian-born Ely De Vescovi (1910-1998) assisted Diego Rivera with several murals, and her discovery of modern fresco techniques in the 1930s was heralded by none other than The New York Times. De Vescovi moved to California in the 1940s and completed four mural panels in the acute mental wards of Los Angeles’s Sawtelle Psychiatric Hospital. She thereafter fell into obscurity until the late 1990s, when her nephew, the late gallery owner Robin Bagier of Ojai, exhibited her prolific and varied work. The Nicholsons own several pieces by De Vescovi, and Bill believes the artist’s later works—which became increasingly spiritual and visionary—resulted from her work at a veteran’s hospital with American soldiers returning from World War II.

Sandi especially loves the regal oil portrait of an African-American woman—simply titled Florence—by Lyla Vivian Marshall Harcoff (1883-1956). “That painting is very important,” says Sandi. “It shows pride, it shows dignity, it shows courage. During the Depression, Lyla—in order to financially survive—established herself as a furniture maker, which led to her making her own frames for the rest of her life.” Born in Indiana, Harcoff graduated from Purdue University in 1904 (one of eight women in a class of 218) and studied in Paris. She eventually moved to Santa Barbara, where she commissioned architect Lutah Maria Riggs to convert a carriage house into her studio/residence. The Santa Barbara Museum of Art gave her a solo show in 1949, and she was widely exhibited during her lifetime. Harcoff also completed several murals for the Works Progress Administration, including a mural at Santa Ynez Valley High School in 1936.

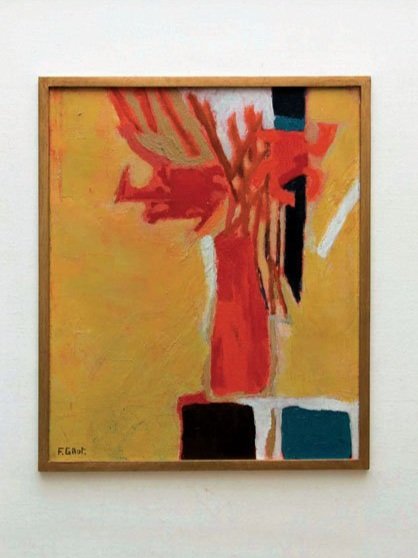

French-born Françoise Gilot (b. 1921) was an artist in her own right when she met Pablo Picasso, with whom she had a turbulent 10-year relationship. After their relationship ended, Picasso instructed all the art dealers he knew not to buy Gilot’s art. The Nicholsons acquired Gilot’s Flowers on a Yellow Field—a brightly colored, almost abstract oil painting for the collection; it is a dynamic example of the artist’s unique talent, as well as evidence of her determination. The Nicholsons have been in contact with Gilot (now 97), and hope to have a face-to-face meeting with the artist who defied Picasso.

The Nicholsons’ curiosity has led them to collect 340 works—dating from 500 B.C. to the present—featuring female artists from all seven continents.

Photography is a strong part of the collection, and American photographer Imogen Cunningham (1883-1976) is one of the standouts. An Oregon native, Cunningham was a contemporary of several noted male photographers who championed her work—Edward S. Curtis (for whom she worked), Edward Weston (who helped exhibit her work), and Ansel Adams (who invited her to join the faculty of the California School of Fine Arts). Cunningham’s photographs were published in Vanity Fair, where she worked from 1934 to 1936. Even so, the major awards she received—fellowship in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and a Guggenheim Fellowship—were granted in the last decade of her life. “Imogen Cunningham was really ahead of her time,” says Bill. “It is just within the last 10 years that photography by women has become recognized and appreciated in the market financially.” The collection’s luminous black-and-white portrait of modern dancer Martha Graham comes from a photo shoot that occurred on a hot afternoon in Santa Barbara. Graham—who spent her teenage years in Santa Barbara—met the photographer at a dinner party, and the photos were taken in front of Graham’s mother’s barn. Cunningham was 48, Graham was 37.

Among the collection’s abstract works is a striking geometric oil painting by Russian artist Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962). An active member of several avant-garde movements, Goncharova’s first major solo exhibition debuted in 1913. Moving to Paris in 1914, she produced costumes and set designs for Sergei Diaghilev’s famous Ballet Russes. She was included in the groundbreaking 1936 “Cubism and Abstract Art” show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and the museum has her work in its collection to this day. As evidence of her continuing importance in the art world, London’s Tate Modern museum mounted a Goncharova retrospective this year.

“As we were putting the collection together, we realized that we really wanted to show the diversity of women. We wanted to show art by women over time and through geography—internationally and throughout the ages.”

For the Nicholsons, every work in the collection has an important backstory to tell. As Sandi says, “We were first attracted to the artwork but soon realized the story or the narrative of the artist’s work and their lives resonated with us in a profound way. The artist’s perseverance, grit, and determination have been as powerful to us as the work itself.”

Understandably, the couple’s ultimate goal is to keep the collection together in an institution where “the girls” (as Sandi fondly calls them) can impact a large number of people on a regular basis. Bill adds, “We’d like to have people free to interact with the collection and hear the stories.” •