Bohemian Rhapsody

The Santa Barbara Historical Museum takes a nostalgic look back at the infamous enclave once thriving on Mountain Drive

Written by Josef Woodard

Photographs: Chiacos (Elias) Mountain Drive Papers, Gledhill Library, Martin (Ed) Photograph Collection, Neely Family Photograph Collection, Peake (Michael) Mountain Drive Photograph Collection, Santa Barbara Historical Museum,

Tooling along Mountain Drive, by car or bicycle, is a classic Santa Barbara ritual. The ribbon of road connecting Mission Canyon with Montecito is speckled with varied architecture—including houses rebuilt after the 2008 Tea Fire—and offers a stunning panoramic view of ocean and city.

“Mountain Drive was known as a haven for artists, societal rebels, revelers, and general free-thinkers.”

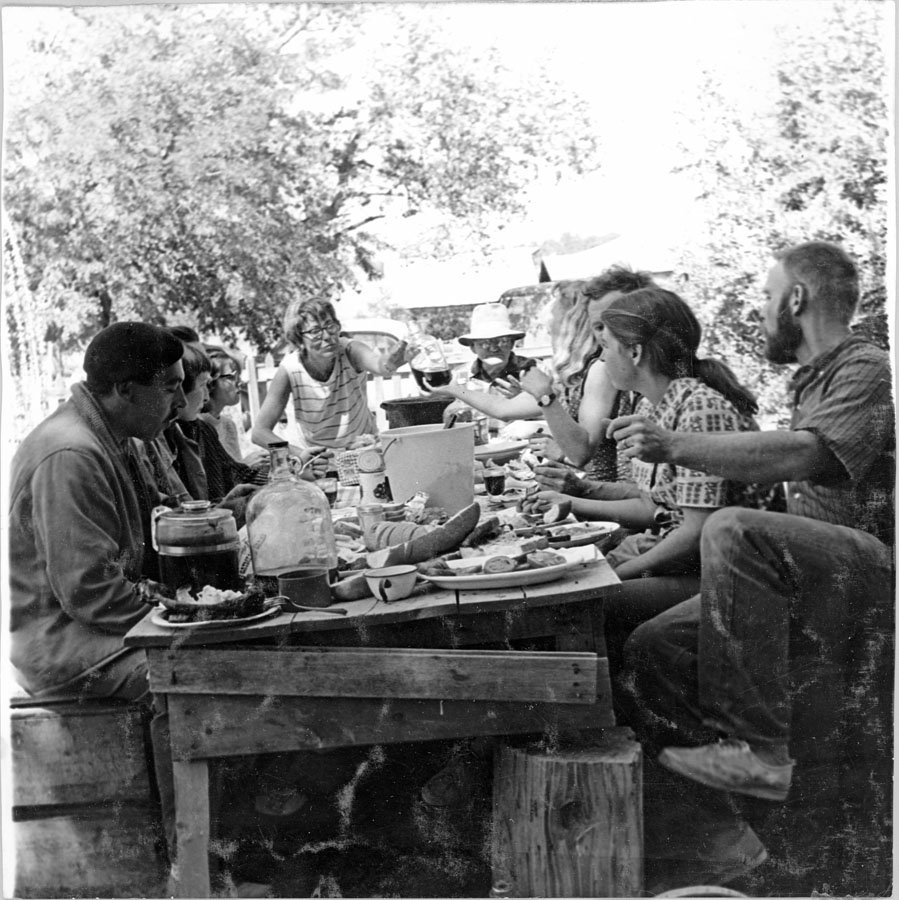

But the 21st-century Mountain Drive barely hints at this area’s yesteryear, when it was home to a thriving bohemian enclave. Between the late 1940s and late ’60s, spanning such movements as the Beat era and hippiedom, Mountain Drive was known as a haven for artists, societal rebels, revelers, and general free-thinkers seeking to create a community beyond the borders of conventional society. The range of festivities and rites up on the Drive featured a raucous, clothing-optional grape-stomping event (its product destined for the Pagan Brothers label), the “Pot Wars” ceramic festival and competition, variations on Maypole ceremonies, and even a celebration of Scottish poet Robert Burns’s birthday. Music of all types provided a ragged, constant serenading presence in those hills.

To get a taste of Mountain Drive’s mythic, maverick past, proceed to the Santa Barbara Historical Museum’s fascinating archival exhibition Memories of Mountain Drive. If the museum has generally leaned into the milder side of Santa Barbara history, this show surprises us with its wilder slice of local lore. Organized by Chris Ervin, head archivist of the museum’s Gledhill Library, and on view through February 28, the exhibit draws on the ample photo archives of Elias Chiacos (author of 1994’s Mountain Drive: Santa Barbara’s Pioneer Bohemian Community) as well as the museum’s extensive oral-history project. In all, the show takes us back and drops us into the intoxicating—and intoxicated—inner life of Mountain Drive in its storied heyday.

Sensory input in the museum gallery includes a folksy soundtrack by the Scragg Family, led by influential bluegrass/folk musician Peter Feldmann, and a looping clip from the quirky John Frankenheimer–directed sci-fi film, Seconds, from 1966, which put Mountain Drive on a broader map of public awareness (although the film, with James Wong Howe’s Oscar-nominated cinematography, achieved only cult-film status). In Seconds Rock Hudson appears as a reborn manifestation of a midlife-crisis-afflicted East Coast banker. He falls in with a free-spirited woman (Salome Jens) who lures him up to Santa Barbara for the bacchanalian revelry of the grape stomp. They end up naked and stomping in lockstep with a vast vat of unclad, unrepressed humanity, high up in the 805. Ironically, the film’s ultimate Faustian message negates the societal escapism represented by the hardcore Mountain Drivers.

“The range of festivities and rites up on the Drive included the raucous, clothing-optional grape-stomping event.”

One defining aspect of the Mountain Drive story relates directly to the tragic legacy and recurring fear of fire in the area. Mountain Drive’s founder and culture shaper, Bobby (Robert McKee) Hyde, acquired 50 acres of fire-scorched land for a relative pittance in 1940 and sold parcels to like-minded free spirits and bohemians-in-training. They built humble houses, mostly of adobe (“unencumbered by building codes,” according to the show’s wall text) and, with 40 families involved by the early ’60s, established a communal enclave of societal outliers.

Fast-forward to the calamitous 1964 Coyote Fire, when many homes were destroyed--including Hyde’s abode. Fire paved the way for the Mountain Drive experiment and fueled the beginning of its end.

Scenes of Mountain Drive, as seen here, included vintage costumes and traditions, humble home-building (usually with adobe) with help from neighbors, and downtown appearances on floats in the Fiesta parade. Elias Chiacos’ 1994 book Mountain Drive: Santa Barbara’s Pioneer Bohemian Community is the most thorough chronicle of the community and history to date.

We gain insights about life on Mountain Drive through black-and-white images on one wall and from a large touch-sensitive screen on which we can scroll through issues of the humble but informative Mountain Drive News and the Grapevine. Less savory aspects of community life include a strong strain of prefeminist sexism, as detailed in Susan Sisson’s oral history.

Another key charismatic Mountain Drive figure was Bill Neely—potter, musician, magnetic mischief-maker, and organizer. According to local resident Dick Johnston, Neely was “about half good and half evil.” One Sandy Hill spoke about a friendly argument in design between Bill’s peasant pottery and the more refined work of Ed Schertz. For his part, Schertz spoke more generally about the Mountain Drive philosophical m.o.: “It was so open…if you weren’t (of) a mass-society orientation, if you were interested in freedom and the exchange of ideas.”

Bobby Hyde’s son Gavin touched on another truth about the place/experiment, commenting that “dad said that people don’t choose the land. The place chooses the people.”

That was then. This is the real estate–booming now. But memories of Mountain Drive, personal and archival, titillate the imagination about another life, time, and place in Santa Barbara. www.sbhistorical.org