Hats Off

Milliner Satya Twena's transcendent move to Ojai was in the stars

Milliner Satya Twena's transcendent move to Ojai was in the stars

Written and photographed by Blue Gabor

When California native Satya Twena came to Ojai from Manhattan with her restaurateur husband, Jeffrey Zurofsky, and daughter, Wish, she had every intention of remaining bicoastal. But the laid-back West Coast lifestyle soon eclipsed her life back East. “Ojai completely seduced me,” she says. “I would sit outside surrounded by trees, the moon, and the stars and think there is nothing more healing nor beautiful than life in nature.” She found herself shuttering her New York hat factory and moving her millinery operations to a converted garage in Ojai’s East End.

Vintage hat forms line her open-air studio, which is scattered with spiritual talismans and vestiges of old-world millinery. Here the interior designer–turned–hatmaker continues to masterfully shape and embellish each of her custom-ordered creations by hand, using materials that include beaver, rabbit, and mink felts and accents that might include gold work and all types of embroidery.

Twena and Zurofsky’s second child, a son named Sage, was born in Ojai, and the family is now settling into their full-time home. Dinners are procured, with Zurofsky’s culinary expertise, from their backyard garden and prepared in an open-fire oven. A spirit of creativity reigns, as the children might be found running around wearing only their own custom-fitted hats.

Twena’s hat making grew from a kitchen operation in an East Village walk-up to a chance opportunity to own one of the last-standing hat factories in the garment district, where she made hats for socialites and celebrities including Usher, Lady Gaga, and Oprah. Today every hat is a custom work of art, made just for the wearer, in a process that begins with a few questions, followed by a Facetime call and sketches. “My hats often symbolize the next rendition of who my client desires to be,” says Twena. She incorporates constellations of iridescent threads in her designs and embroiders mantras or intentions in the linings. Like those who wear them, no two Satya Twena hats are alike.

“I believe my clients seek my work because I do the spiritual and emotional work. I meet them as an open vessel with the sole purpose of fulfilling their desires and intentions, and the rest is magic.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

A Lifelong Love Affair

Beverley Jackson’s daughter reflects on the life and legacy of an icon

Beverley Jackson’s daughter reflects on the life and legacy of an icon

Written by Tracey Jackson

For years my mother, the late Beverley Jackson, had been calling herself the Doyenne of Montecito. Then at some point the borders expanded to include Santa Barbara as well. She would season the most mundane stories with the phrase: “I went to Vons, and four people said, ‘There is the doyenne,’” she’d say. I would do an internal eye roll. Oh, there goes mom again. Because, you know, doyennes are prone to exaggeration.

But I came to learn in her final years that mom really was the Doyenne of Santa Barbara. And her followers, fans, and acolytes covered the gamut, from those who worked in restaurants to celebrities and royalty, from socialites to the cashiers at Vons.

According to the Oxford dictionary, a doyenne is “a woman who is the most respected or prominent person in a particular field.” One might then ask what exactly was her field of expertise?

The woman did so many things over her nearly 92 years. She was a writer, a scholar of Chinese textiles, a wonderful photographer. She was the social columnist for the News-Press for several decades and then went on to write for other publications up until weeks before her death.

In her last years she was an artist, creating collages, pine-needle baskets, and jewelry. She was part of group shows and had a few one-woman exhibits. Pretty impressive in your nineties! Her books on China won awards. She lectured all over the world about bound feet and kingfisher feathers. She had very disparate and particular avenues of interest and expertise.

Yet no matter where she went or what she did or whatever side alleys of interests she wandered down, her heart and her allegiance and her love affair were always with Santa Barbara.

It wasn’t just geographical. We would return from exotic locales, and she would always say, “When I make that turn near the Rincon and see my mountains”—her mountains—“I realize there is nowhere in the world as beautiful as my Santa Barbara.” Again, for the record, her Santa Barbara.

When she walked along “her beach”—doyennes have an affinity for possessive pronouns—she would sigh, “There is no beach in the world to compare to this.”

The thing is, she meant it. While her house looked like someone picked it up from 1930s Shanghai and moved it to Montecito, her soul was always in Santa Barbara. And despite her ownership and adoration of the mountains and sea, it was really the people here she loved.

The people of Santa Barbara took her in at a time in her life when she needed that kind of shelter, and she gave back to them and the community nonstop for the rest of her life.

Many know of her today from elaborate stories she loved to tell about the movie stars who were her friends and the fabulous places she’d been. People knew her infectious laugh and the fact that no one could remember a time when she wasn’t around.

Mom left Los Angeles and moved to Santa Barbara in 1962. She was married with a young child. Within a year and half she would be a divorced single mom to an only child. That may not sound like much of a tragedy today, but in 1962 it was an uncommon occurrence. In fact, I was the only child of divorce at Laguna Blanca for most of my childhood.

Bev had been pretty protected by her parents. She went from their home to her marital home—a very comfy setup in Brentwood with a nanny for me and a guy that drove my dad around and worked around the house.

Suddenly she was on her own. No nanny. No husband. Just the two of us on a hilltop in Hope Ranch. She found herself unprepared for what life had dished out. But somehow, with her endless curiosity, steely determination, and spunky personality, she looked around and told herself, I am going to run this town.

Okay, I don’t know if she really said those exact words, and if you had ever asked her what she told herself during those early years, I’m not sure she would have put it in those terms. But knowing her the way I did, I know that is what she thought.

Santa Barbara in the 1960s was filled with the most interesting people. And it had its share of doyennes-in-residence: Pearl Chase, who preserved the community’s traditional charm and architecture; Lutah Riggs, the titanic midcentury architect; and Ganna Walska, the opera singer and creator of Lotusland. These were all true doyennes, and Bev longed to be one of them. But I don’t think she was projecting 60 years down the line. She simply wanted a place in the community, a position in society. And she wanted to make a home for us. Sure mom invented herself; most well-known people do. She turned herself into the woman she wanted to become. And she stuck with it until the end.

I have to say, being a doyenne has its perks, even posthumously. I called Lucky’s recently, in advance of what would have been Bev’s 92nd birthday. I wanted to take my kids to that restaurant and celebrate her. I called—no tables until late. I wasn’t speaking to the manager, so I asked the person’s name and how long he’d been there. “Over twenty years,” he replied. “Do you know who Beverley Jackson is?” I asked. “Of course,” he said, “everyone does.” I got the table.

So she’s still the Grande Dame—one of the most revered, honored, known residents of Santa Barbara. She worked for it, she earned it, and she coveted it.

See the story in our digital magazine

Through the Eyes of the Future

How Leah Thomas is redefining the environmental movement

How Leah Thomas is redefining the environmental movement

Written by Olivia Seltzer | Photographs by Mark Griffin Champion

If you’ve been on Instagram any time in the past six months, chances are you’ve seen countless graphics educating and informing on the Black Lives Matter movement, racism, and racial justice—to name a few. Twenty-five-year-old Ventura local Leah Thomas—or @greengirlleah, as her nearly 160,000 Instagram followers know her—is the creator of one such viral post. But hers was a little different from the other infographics that might have come across your feed. Instead of focusing on racial or environmental justice, it combined the two, addressing what Thomas calls “intersectional environmentalism.” The pioneering activist, who has written on the subject for publications such as Vogue and The Good Trade, is certainly more than qualified to inform on this topic, having studied environmental science and policy at Chapman University and worked on the PR and communications team for Patagonia—a leading “one-percent for the planet” corporation globally renowned for its passion for the preservation and restoration of the natural environment. I spoke with Thomas over Zoom to learn more about this relatively new term and how we can all be intersectional environmentalists.

How would you define intersectional environmentalism? Why is it important for people to become intersectional environmentalists? Intersectional environmentalism is a type of environmentalism that advocates for the protection of both people and the planet. It amplifies the voices and efforts of diverse individuals and marginalized communities and gives them a place in the environmental movement. I had worked at a lot of environmental organizations, and I had been in a lot of environmental spaces—I studied environmental science and policy at Chapman University—but I wasn’t seeing a lot of acknowledgment for environmental justice.

Where did you first hear the term intersectional environmentalism? Was there a moment that really made you think, “I need to get involved”? I first heard the term when I wrote it. I Googled [the term] and didn’t see it anywhere. When it started to kind of go viral was after I made a graphic—Environmentalists for Black Lives Matter—in May, and when you swiped through it, it had my definition of intersectional environmentalism.

There have clearly been a lot of conversations surrounding race in the United States over the past few months. How do environmentalism and climate change come into play? Environmentalists often talk about confined animal feeding lots or endangered species, but they won’t talk about the communities that are impacted by those environmental injustices. One way to start is to really make those connections, and for environmentalists to ask, “Who?” And if the “who” ends up being people of color or low-income communities time and time again, I think it’s time to acknowledge that maybe the environmentalism that we have now and the environmental policies that we have now might need some reworking to include people of color.

What drew you to work for Patagonia out of college? Can you tell us about your experience at the company? I was in a corporate sustainability class, and I learned about the triple p’s: people, profit, and planet. We had a case study about Patagonia, and I remember just thinking, “Huh, that makes sense. I’m going to work there one day, because it seems like they’re doing things right.” I ended up as an assistant on the PR team and to [Vice President of Environmental Initiatives and Special Media Projects] Rick Ridgeway. I learned a lot about how to flip capitalism on its head and help fund activism through a corporation, which really inspired the work I’m doing now. It was great to work in an environment with so many people passionate about activism and environmentalism.

How do you think people can live a more sustainable, environmentally friendly life? I don’t think there’s one way to be an environmentalist or to save the planet. I think it takes all of us doing different actions. That might be someone being super passionate about food justice, and maybe that means eating a plant-based diet or reducing their meat intake. If someone’s really passionate about environmental justice, maybe that means signing petitions and amplifying things on social media.

What does your ideal world look like, and how do you think we can get there? The future should be intersectional, and I think to get there it really just means acknowledging our differences and the beautiful things in our differences, and also some of the hard conversations surrounding our differences.

Who are your role models? Kimberlé Crenshaw [civil rights advocate who developed the theory of intersectionality]. Rick Ridgeway, who was my boss at Patagonia and a famous rock climber. And then my grandmother, Janice.

Do you have any exciting projects coming up that you can tell us about? [Intersectional Environmentalists] is launching a business accountability program to teach businesses how to incorporate intersectionality into their business framework, so they can be more similar to Patagonia and do things that are better for people and the planet. Also, I’m working on a book proposal currently, so that’s really exciting.

Final question — if there’s one question you could ask yourself, what would it be, and could you please answer it? I would ask, “Why am I such a perfectionist, and how can I relax?” I would remind myself that it’s okay to not always live in survival mode, and to take a step back. It’s okay to make mistakes.

See the story in our digital magazine

Kule + The Gang

Work imitates life during quarantine for this Carpinteria family

Work imitates life during quarantine for this Carpinteria family

Written by Madeleine Nicks | Photographs by Dewey Nicks | Styled by Deborah Watson

When COVID-19 swept the nation, schools closed, travel plans halted, and our family, like many others, was stuck at home. But instead of confining ourselves to days filled with nothing but Zoom meetings and disinfecting groceries, we found joy in the beauty of Carpinteria. We started each morning with low-tide beach walks, took local hikes filled with vibrant wildflowers, biked through Summerland, held family tennis matches and mother-daughter ballet classes. All at once we fell back in love with a community we had taken for granted. Every sunset and sunrise was magical, and every new activity we stumbled upon was a chance for exploration. A few weeks after the quarantine officially started, my dad, Dewey Nicks, was catching up about life in the time of Corona with his longtime friend and stylist extraordinaire Deborah Watson. Upon hearing what we’d been up to, she suggested a long-distance fashion shoot centered around Nikki Kule’s namesake brand, KULE. The timing for an introduction worked out perfectly, as Nikki had recently reposted a cover of Yolanda Edward’s magazine, YOLO Journal, which my dad had photographed. Soon we received a huge box filled with KULE clothing. Opening the box felt like Christmas morning in the beginning of May, with all of us digging through the packages and excitedly trying on all the pieces. And because KULE’s clothes are so versatile, everybody in our family found multiple things they loved. Debra styled us over Zoom, mixing and matching the bright colors, classic stripes, preppy sweaters, T-shirts, pullovers, and blouses. Our family spent the next week hitting our favorite spots in Carpinteria, Santa Barbara, and Montecito, changing outfits along the way. When my dad saw a spot he liked or light that interested him, we would pull over, and he’d shoot. The places we found the most comfort in during quarantine also gave us the most inspiration to be creative, to find new ways to use our home, and to change our perspective on how to be artistic within the limits of our changing world. And, yes, we all still wear our KULE clothes every day. •

See the story in our digital magazine

Where Freedom Reigns

From his ranch in Santa Ynez, artist Cole Sternberg envisions a new destiny for California

From his ranch in Santa Ynez, artist Cole Sternberg envisions a new destiny for California

Written by L.D. Porter | Photographs by Sam Frost | Produced by Frederick Janka

A large, weather-beaten tractor sits in front of the metal-clad barn that serves as Cole Sternberg’s art studio in Santa Ynez. It’s an oversize symbol of how the artist’s life has changed since he and his wife, Kelsey Lee Offield, relocated here almost four years ago from Los Angeles. The couple now has a two-year-old daughter and an animal menagerie featuring chickens, pigs, a rescued mini horse, and a very friendly Saint Bernard. The entire homestead (residence, guesthouse, and studio) is solar powered. They’re even growing their own wheat to make flour.

But don’t let the bucolic scene fool you; in addition to the barn/studio, there’s a photography darkroom, a silk-screening room, and a kiln for ceramics. It’s really an art-making compound that just happens to be in the country. As the artist happily admits, having a ranch has “allowed me to think a little differently and create things with more flexibility. Now I can drag paintings in the dirt, leave them out in the wind or on a tree for weeks.”

As an internationally acclaimed artist whose works reside in major collections, Sternberg is known for exposing his art to the environment—especially ocean water—and goes to great lengths to obtain his desired artistic effects. In 2015, during a dramatic 22-day voyage on a shipping vessel from Japan to Portland, Oregon, he threw one of his paintings into the water and watched it drag alongside the ship. After retrieving it, “it felt like this miracle,” he says, “because you really felt the water in the work. So that started me off exploring creating environmental patterns [on paintings]; whether it’s the movement of the water, or light through a forest, or rings of a tree. All those things come out when you expose them to the elements.”

Born in Richmond, Virginia, Sternberg had a peripatetic childhood that stretched from Saratoga, California, to Stuttgart, Germany, during his middle school years. By the time his family returned to California, “I’d seen 30 countries and fell in the fountain at the Louvre,” he says. Pennsylvania’s Villanova University followed, coupled with a return to Germany for a study-abroad year, culminating with a B.A. degree in fine arts and business.

His next step was highly unusual—at least for a future artist: He earned a law degree from American University in Washington, D.C. “I was always drawing or painting, but I didn’t think [making art] would be a viable way to buy food or have a roof over my head,” he explains. (Even so, he mounted his first art show at a bar during law school.) An entertainment law internship brought Sternberg to Los Angeles, where he finally ditched his day job to become a full-time artist.

As it turned out, his legal background provided the impetus for Sternberg’s most ambitious and far-reaching project yet: an exhibition documenting the infrastructure for a new country known as The Free Republic of California (thefreerepublicofcal ifornia.com). Although the premise of the work assumes California has seceded from the United States, secession is not the primary focus. “It’s more about what a more enlightened nation could look like,” says the artist, who wrote a 54-page budget for the new country, recasting funds California currently sends the federal government for income taxes and directing those funds to uses he considers more effective: universal health care, free higher education, low-income housing, and more.

Sternberg also drafted a new constitution addressing many issues currently confronting America—a document that “redefines a constitution for modern times with dreams of peace and environmental stability at the forefront.” There’s no electoral college, the death penalty and torture are outlawed, weapons are strictly regulated, and political campaign financing is severely limited. Discrimination based on race, sex, age, origin, language, religion, sexual orientation, conviction, health and/or disability is prohibited, and equal pay is guaranteed regardless of sex.

Of course, Sternberg’s art figures prominently in the exhibition, including a new hand-stitched California flag, official seal, and letterhead. He designed campaign-like propaganda posters, lawn signs, and buttons. He even created a clothing line, and silkscreened 500 items by hand. (The first batch of custom clothing was stolen from a warehouse, but the artist—true to the cause—hopes he’ll see protestors at future demonstrations wearing contraband Free Republic of California T-shirts.) Works on paper blending his painting practice with vintage photographs of Yosemite National Park are also part of the show. The exhibition, “Freestate: The Free Republic of California,” opens October 8—virtually and by appointment—at ESMoA in El Segundo (esmoa.org).

See the story in our digital magazine

Roman Holiday

An architect's Ojai home is inspired by the Eternal City

An architect's Ojai home is inspired by the Eternal City

Written by L.D. Porter | Photographs by Tim Street-Porter | Produced by Frederick Janka

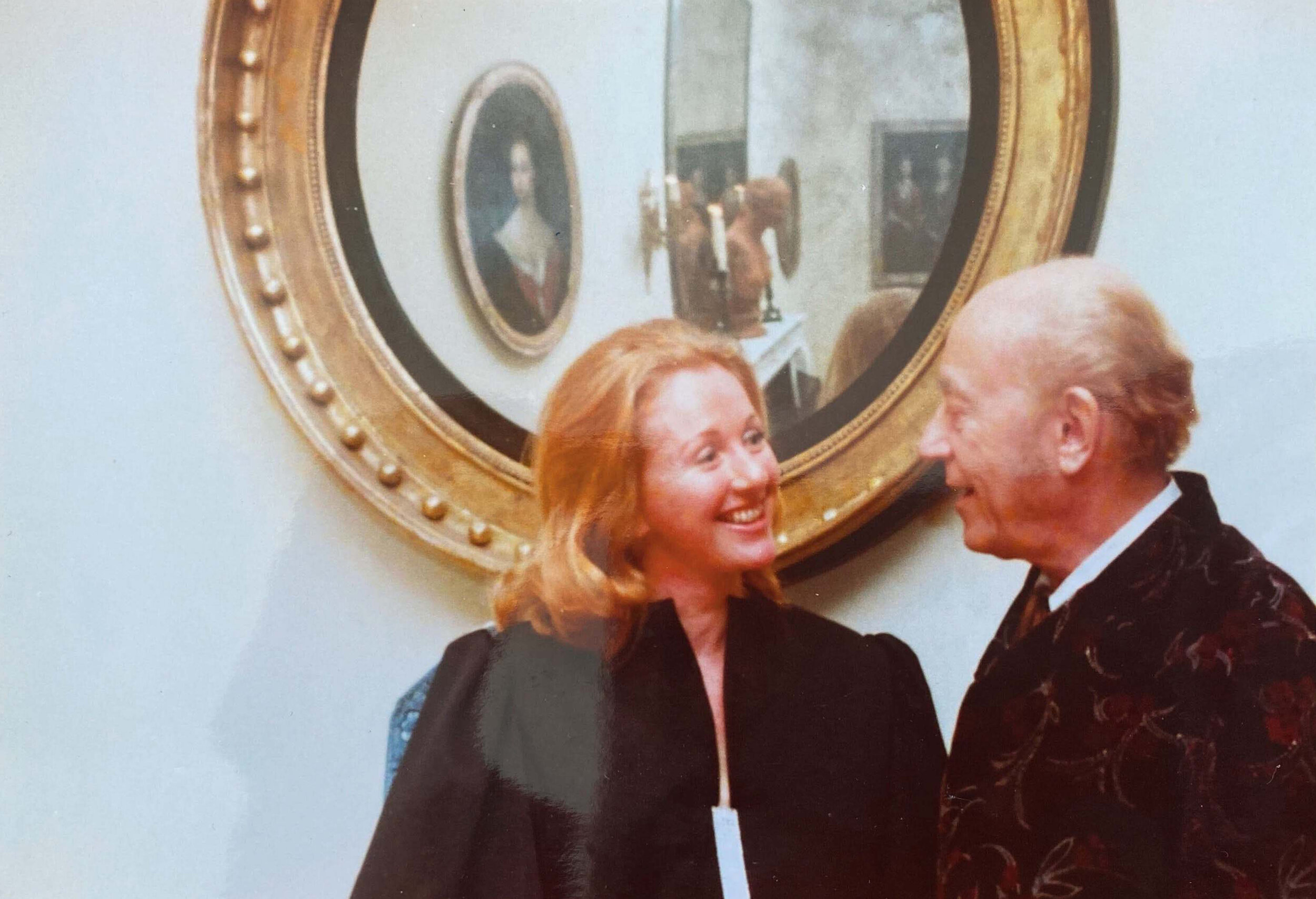

A medieval proverb proclaims “all roads lead to Rome,” but for architect Frederick Fisher, Rome led to Ojai, where his contemporary home reflects the transformative experience of a year spent in the Eternal City with his wife, Jennie Prebor, and their two sons, Henry and Eugene.

It was not your average family trip to Europe. In 2008, Fisher received the prestigious Rome Prize awarded annually by the American Academy, an august cultural institution established in 1894 by such prominent Americans as John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and William K. Vanderbilt. Presented to 30 artists and scholars in various fields, including architecture, design, and literature, the prize also features a lengthy stay at the Academy’s iconic hilltop compound.

“It changed our life, for life,” says Fisher of the sojourn. Upon returning to their Los Angeles home, the couple hosted a fundraiser for the academy’s Rome Sustainable Food Project, which focuses on feeding academy residents in an environmentally sustainable way. The event was held in Ojai, and Prebor was immediately hooked on the community: “I thought, I could live here. That was it,” she says. Fisher was already a convert, having designed a house in Ojai years earlier for artist Elyn Zimmerman.

The couple found a deserted nine-acre hilltop plot in downtown Ojai, derelict but packed with promise, including spectacular mountain and valley views. An extensive cleanup uncovered a series of stone terraces and an olive grove, in addition to the remains of an old cistern.

The land could have been subdivided and developed, but Prebor and Fisher were determined to keep it intact. “This is such a rare type of property that it’s a legacy,” explains Fisher. “You’re taking care of a legacy. It’s a treasure.” Adds Prebor, “It’s about preserving the site and having the site not just for our family but for the community, too, to have community events.” In fact, the couple sponsored several fundraisers on their grounds years before their house was built. Both Prebor and Fisher are arts supporters; many of Fisher’s projects include artist collaborations, and Prebor is an art world veteran. Together they’ve supported Ojai’s Carolyn Glasoe Bailey Foundation; as Frederick Janka, its executive director notes, “Jennie and Fred were early adopters of the foundation from the start. They’re real patrons of the arts and artists.”

The existing topography dictated the home’s design. “It’s a beautiful hilltop site, and there’s something unique about that as an architectural problem,” Fisher says. “You think of Tuscan hill towns and those little villas sitting on top of the hill like a box. Basically, that’s what this is; it’s the box on the hill.” The architect used a prefabricated structural insulated panel system to construct the three-story structure. Clad in rusted corrugated metal, the material harks back to the couple’s origins. (Prebor is a Pennsylvania native; Fisher hails from Ohio.) “Jennie and I are Rust Belt people,” Fisher says, “and the look of the timeless, rusted barn to me was a natural for this site. It’s ageless, and it requires no maintenance.”

From the start, the kitchen’s design was of paramount concern. According to Fisher, “The design of any house starts with the kitchen, because I know that the kitchen is going to be the center of life no matter what.” Prebor’s professional experience in the catering world added an additional requirement—the ability to entertain large groups. They needed, she jokes, “a house for the four of us that can entertain a hundred.” The result is an airy, double-volume space with a fire-engine red central island and custom cabinetry by artist Roy McMakin, who also created the kitchen’s bright yellow Dutch door with classic diamond-pane windows. “It’s like the midwestern suburban house kitchen,” says Fisher. “It’s a take on a vernacular that I’m very comfortable with.” Pre-COVID, the house was a welcome break from Los Angeles, where Fisher’s architecture office is based, but in the wake of stay-at-home

orders, the entire family has embraced Ojai full-time. Prebor owns a chic downtown boutique—Blanchesylvia, inspired by a shop in Rome—that features dresses, vintage finds, and beads. Fisher replicates his life in Italy through daily rituals: Mornings are consumed by espresso and the newspaper; midday he’s in the library surrounded by books and work; and the day ends with a glass of wine in the living room, gazing at the sunset mountain view, Ojai’s famous “Pink Moment.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

Fresh Grounds

Just north of Santa Barbara, where the ocean mist rises above the sloping terrain of the Goleta foothills, a revolution is brewing

Just north of Santa Barbara, where the ocean mist rises above the sloping terrain of the Goleta foothills, a revolution is brewing

Written by Ninette Paloma | Photographs by Michael Haber

At 5:45 a.m., Jay Ruskey pulls himself out of bed, stretches, and sets off to make the first of what will be many cups of coffee. He warms the pot, rinses the filter, and slowly and methodically pours water over medium-coarse Good Land Organics Geisha (one of several possible choices), carefully inspecting his CO2 bloom. The ensuing cup—with its heady aroma of chocolate, floral, jasmine, red apple, rose, and sweet vanilla—is the preternatural result of Southern California’s latitude and climate, and a liquid testament to Ruskey’s unyielding resolve.

“So many of us enjoy the ritual of coffee but we don’t understand how much work goes behind developing it,” says Ruskey, founder of FRINJ coffee and owner of the first commercial coffee farm in California. “The planting, harvesting, roasting, and brewing are all part of a complimentary journey that’s on par with the wine experience.”

Two decades ago, Ruskey’s idea to incorporate several rows of coffee plants into his avocado orchard was met with skepticism by industry experts who insisted California lacked the characteristics needed to foster a notoriously delicate crop. But Ruskey was undeterred. “The truth is, I didn’t take them or anything too seriously,” he recalls. “At that point in my life, I was young and ambitious and just trying to find crops to make a living.”

Through years of exploration and error on his family’s Good Land Organics farm property—along with a savvy collaboration with leading researchers at UC Davis—Ruskey finally developed a replicable farming system that would consistently yield a high-quality crop, and suddenly the idea of subtropical coffee production didn’t seem so far-fetched after all.

“Growing coffee in California is different in both how the coffee is produced and how it is experienced,” emphasizes Ruskey. “We have a cross-section of climate with an ocean and mountain buffer that’s always lent itself to agricultural diversity. Throw in 14 hours of sunlight and 20 percent humidity that invigorates sweet cherries, and that’s what we call the California advantage.”

Aficionados are dubbing it the “California Coffee Experience,” and consumers from Japan to the U.K. want in on it, too. “It’s an honor to be recognized for the craftsmanship,” Ruskey says with a smile.

Today, FRINJ is initiating a new chapter in the state’s agriculture, in which regenerative farming and biodiversity are at the center of a sustainable approach to land stewardship. “The new farmer is looking for a lifestyle they can be proud of,” says Ruskey. “Their farms may be smaller, but they’re looking to improve on their property using conscious methods that are good for the land and people.” Making good on that philosophy, Ruskey has also pledged to do right by farmers who’ve historically seen meager returns on their labor-intensive crops—generally hovering around the 2 to 5 percent mark. By stark contrast, FRINJ farmers walk away with a sizeable 60 percent return, signaling a firm and clear acknowledgment that their time and efforts are valued.

“It’s completely upside down right now,” says Ruskey, “and I want to be a disrupter. This is about farmers caring for each other and looking after the land together.”

On a late spring afternoon, the farm is buzzing with harvest activity, and Tejon the family dog is making his rounds, sniffing at crates and greeting the crew as they gather in the main house for an informal tasting. FRINJ’s San Franciscan bean roaster is whirring in the corner, and the faint smell of lightly browned butter begins to fill the sunlit shed. “We’re not a dark roasting coffee,” Ruskey explains. “We don’t want to narrow the flavor profile.” Like an expert chemist, Ruskey begins gliding around the tasting bar, setting out small ceramic cups and carefully monitoring the water. He pours samples of one of his newest varietals, part of a new breeding program that develops FRINJ-produced hybrids. The floral notes are unmistakable, with a delicate nuttiness and a sweet, rounded finish. It is undeniably the best cup of coffee I’ve ever tasted, and everyone around me nods in agreement.

“I think our quality is at world standards,” Ruskey says with a proud smile. “It’s really up to our California farmers now, and we’re pushing the limits and going for it.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

S.O.S.

When the world is in crisis, Direct Relief International is here, there, and everywhere

Emergency medical aid departs Direct Relief’s warehouse on Oct. 2, 2024, bound for communities impacted by Hurricane Helene. The shipments were made possible by FedEx. (Maeve Ozimec/Direct Relief)

Reposted for Hurricane Helene relief

Reposted for Hurricane Helene relief

Donate hereA Week In, Hurricane Helene's Impacts Still Reverberate Across Multiple States

By Sofie Blomst, Direct Relief

Relief and recovery efforts continue across the southeastern U.S. and southern Appalachia following Hurricane Helene. The storm, which made landfall as a Category 4 hurricane over Florida's Big Bend region late on September 26, brought devastating winds of up to 140 mph, a life-threatening storm surge that reached 16 feet, and torrential rains, triggering widespread flooding and debris flows and leaving an 800-mile path of destruction.

Preliminary reports indicate the storm's passage has resulted in at least 170 deaths, while hundreds more remain missing. The storm also caused severe damage to critical infrastructure, including houses, roadways, and water systems; disrupted communications and other essential services; and prompted U.S. health officials to declare Public Health Emergencies for Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina.

In addition, as of October 2, more than 1.2 million customers in Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia remained without power, causing disruptions to critical health services, including due to the loss of temperature-sensitive medications and vaccines, and putting those reliant on electrically powered medical devices and medicines requiring refrigeration at heightened risk.

In response, Direct Relief has made available $74 million in medicines and medical supplies and $250,000 in financial assistance to community health centers, free and charitable clinics, and other healthcare partners in affected areas.

Direct Relief has staff on the ground in affected states, including Florida and Georgia, and is coordinating closely with state and national associations as well as healthcare providers to assess damages, identify priority needs, and respond to requests for emergency medical aid.

DIRECT RELIEF'S RESPONSE TO HURRICANE HELENE

As of September 30, Direct Relief had dispatched 14 shipments of specifically requested emergency medical aid, including antibiotics, emergency medical backpacks, DTaP vaccines, hygiene kits, oral rehydration salts, over-the-counter products, personal protective equipment, water purification tablets, and medications to manage chronic diseases, for healthcare providers responding to the needs of hard-hit communities in Florida, North Carolina, and Tennessee. The shipments include 20 emergency medical backpacks and 150 household hygiene kits for Appalachian Mountain Health, which serves communities in Asheville, NC, which suffered catastrophic flooding and damages due to Hurricane Helene, and the nearby towns of Murphy and Robbinsville.

Additionally, from September 24 to October 1, Direct Relief delivered 42 shipments of essential medicines and supplies to healthcare providers in affected states as part of its Safety Net Support Program; the program seeks to ensure community health centers, free and charitable clinics, and other local healthcare providers across the U.S. have access to ongoing donations of medicines and medical supplies for their low-income and uninsured patients and helps build health facility resilience to respond to and quickly recover from shocks, including those caused by extreme weather and climate events, emergencies, and seasonal demand surges.

Medications shipped to the storm-affected areas regularly include insulin, mental health medications, and blood thinners. People dependent on these medications could face profound consequences without them. People without needed insulin, for example, may have prolonged elevations in blood sugar which can lead to life-threatening diabetic ketoacidosis. Additionally, people who have been stable on antidepressants may face increased risk of mental health crisis, while people without access to needed blood thinners are at increased risk of a stroke. With baseline diabetes, asthma, and hypertension rates exceeding national averages in many of the affected areas, there is a heightened risk for unmanaged chronic diseases to cause sudden health crises.

In addition to the above response efforts, Direct Relief emergency response personnel are conducting site visits with several healthcare partners in Florida. During the week of September 30, Direct Relief staff visited Evara Health, a community health center with 17 locations throughout Florida's Tampa Bay area, and the University of Florida Mobile Outreach Clinic. Following Hurricane Ian's impact on Florida in September 2022, Direct Relief, in partnership with the Florida Association of Community Health Centers, funded the retrofit of a mobile medical unit for Evara Health.

The health center recently deployed the mobile medical unit to provide critical health services for communities in Pinellas County, which faced disruptions of power and water services, extensive flooding, and significant property damages following Hurricane Helene. Similarly, the University of Florida Mobile Outreach Clinic is using its Direct Relief-funded mobile medical unit to offer a weekly rotating clinic in rural communities. Another Direct Relief-supported organization, Cherokee Health Systems, reports deploying their mobile clinic to assess needs and support community response efforts in East Tennessee's Cocke, Hamblen, and Green counties.

HURRICANE PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE CAPACITY

As part of its annual Hurricane Preparedness Program, Direct Relief stages Hurricane Preparedness Packs in hurricane-prone states and territories along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, the Caribbean, and the Pacific. These packs, containing more than 200 items, are critical to ensuring the continuity of care for as many as 100 patients for 72 hours in the wake of an emergency. As of the June 1 start of the 2024 Atlantic Hurricane Season, Direct Relief had prepositioned 30 packs with safety net providers in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia.

In addition, through its ongoing support, Direct Relief maintains an extensive network of 276 health partners in Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee. During the previous five years, Direct Relief has mobilized more than 28,000 shipments comprising more than $561 million in essential medicines, medical supplies, and medical equipment for these health partners. During emergencies, Direct Relief can quickly tap into this network to identify priority needs and mobilize medical resources for healthcare providers that are already vetted by Direct Relief and well-established and trusted among impacted communities.

This story was originally published by Direct ReliefWhen the world is in crisis, Direct Relief International is here, there, and everywhere

Written by Hollye Jacobs | Photographs by Sam Frost

Santa Barbara has an uncanny ability to attract some of the most interesting, engaging, passionate, and philanthropic citizens of the world. Thomas Tighe is no exception. As the president and chief executive officer of Direct Relief International— with compassion, grace, and steadfast equanimity—he stewards vital medical and disaster relief support to communities in need in all 50 states and more than 100 hundred countries annually from their distribution center based in Santa Barbara.

How do you prioritize where you are going to deploy Direct Relief assets? With a keen sense of responsibility, empathy, and pragmatism. For 72 years, Direct Relief has prioritized the places and people with the fewest resources, in the greatest need, and with the least access to the type of essential medical resources the organization typically provides. And we assign a higher priority to activities focused on women’s and children’s health, in large part because those areas have not received anywhere close to what makes sense from almost any perspective.

How has COVID-19 impacted your day-to-day operations? The effects of the pandemic have been profound for every person, business, government, and organization, and Direct Relief is no exception. Because much of what’s been needed to respond to the crisis are things that Direct Relief does routinely, it’s required a rapid scaling-up and readjustment to do more, faster, and in more places simultaneously than at any time in our organization’s history.

We did have the benefit of an early signal of just how serious the situation was likely to be based on our experience in China when the outbreak of a novel coronavirus first occurred. Despite having done very little in China historically and zero expectation of being either asked by or permitted to assist in China, we were contacted directly by the largest medical facility in Wuhan and asked for urgent assistance. We were in a position to respond, recognized that containment of the virus was essential, so we moved fast and were able to assist with emergency charters that FedEx arranged to deliver PPE and other items that we stockpile routinely. Having seen how events unfolded there, we were already sprinting when the first cases appeared on the West Coast, and then everywhere else in the United States and in other countries.

What is your most memorable experience with Direct Relief? My time at Direct Relief has left me with a mosaic of experiences—both inspiring and heartbreaking—that are burned into my memory. Those that surface most often are not associated with a major event like the pandemic we’re in or being in the mountains of Nepal when an 8.0 quake happened. They are variations of our work bringing me into contact with a person whose actions or entire life reflect such a pure dedication or selflessness that is far beyond what I could ever express in words. Heroes abound, and they never think of themselves as heroic. I think everyone on the Direct Relief team has their own version of these experiences, which is a rare privilege in life.

How did your personal experiences with natural disasters (i.e., the debris flow of 2018) impact your professional decision-making? It was a sharp reminder to me that every disaster is not only a local event but a very personal one to everyone affected by it. The human dimension is much more complex and far less visible than the necessary practical actions that need to be taken after a tragedy like the debris flow, and both take a long time to deal with and bounce back from.

We are a support organization, so the critical decision at work is always where the support is aimed. In Montecito, it was easy to plug in immediately with our local first responders because we know them and also know that they’re among the most skilled and talented in the world. But we also saw how important the start-up groups were, with the Santa Barbara Bucket Brigade being a perfect example of inviting participation, organizing in a thoughtful practical way, and just showing through their words and action empathy and personal concern for their neighbors.

When going through a tough time, knowing that someone is pulling for you and cares about you helps you get up in the morning. Direct Relief always tries to do that, and we did everything we could think of to help in our hometown.

What are your biggest challenges? Direct Relief faces the same challenges every nonprofit organization that relies entirely on private support confronts in economically uncertain times. The organization is assiduously apolitical and always has been, which presents some challenges during what I think is fair to say is a time of heightened political intensity. I think huge opportunities exist to address vexing problems that Direct Relief focuses on—access to health services for people who just can’t afford what’s needed, anticipating and responding to large-scale emergencies—by simply focusing on the issues and inviting the participation of everyone who has an important piece of the puzzle.

When I was growing up, “public service” meant “working for the government.” Things are much different now. Working for the government may not seem as attractive, but the underlying idea of public service—doing things that help our neighbors who need it, preserving our natural environment—are pretty basic, good, important things. Those things can be done, including at scale as we’ve seen at Direct Relief. So, the big challenge that we see as an enormous opportunity is to harness all the talent and tools and resources that exist, but in a different way that invites folks to participate.

How did your experience with the Peace Corps influence your work at Direct Relief? Being a Peace Corps volunteer gave me such a different view of everyday life in a place so different from everything I knew. I was there to work, but like every other Peace Corps volunteer ever, I learned that I’d fail miserably unless I understood the culture, language, and customs so I could communicate and navigate in a way that made sense where I was, not where I came from. That experience has been particularly helpful at Direct Relief particularly with regard to scale, embracing technology to do things differently, and making sure that any money being spent was advancing the mission in the most efficient way possible. •

See the story in our digital magazine

Z-Girl

Revolutionary skater, surfer, artist and activist Peggy Oki keeps the stoke alive

Revolutionary skater, surfer, artist and activist Peggy Oki keeps the stoke alive

Written by Jim O'Mahoney

Enter the Zephyr Team: Dogtown's finest, feral and on fire, led by Jeff Ho and Craig Stecyk lll. These guys attacked with nonstop grind, handstand, powerslide, low hand plants, '70s surf moves with skate tricks thrown in and with a lot of improv.

The crowd howled a nonstop hoot! When the boys were done, Zephyr's only female member surfer, skater Peggy Oki was called up. When rolling into the arena she immediately slowed down the pace with a controlled and focused routine, hand down low turns, wheelies, 360s, a perfect flowing surf skate presentation softening the blow of rad.

When the smoke cleared, Peggy Oki had won the gold and became the first National Freestyle Skateboard Champion.

See the story in our digital magazine

An Evolving Soundscape

The Music Academy of the West continues to find new ways to embrace its mission and the community

The Music Academy of the West continues to find new ways to embrace its mission and the community

Written by Joan Tapper | Photographs by Sam Frost

For 73 years, the greater Santa Barbara community has had a love affair with the Music Academy of the West. And even in the unparalleled circumstances of the summer of 2020, that relationship has been carried on with the imagination, innovation, and pursuit of excellence that have distinguished the Academy since it was founded as a summer music school by luminaries including opera star Lotte Lehmann and conductor Otto Klemperer, along with prominent Southern California art patrons.

“The community has always cherished the Academy,” says president Scott Reed, “and the Academy has created programs to welcome the community. We have performance-based training, and the community is vital to our success.” Traditionally the fellows—as the talented young vocalists, pianists, and instrumentalists are known—gather on the gracious Miraflores estate in Montecito for classes and seminars with faculty drawn from world-class conservatories and orchestras. They perform in master classes, picnic concerts, chamber music, operas, and much more. “It’s important to get the fellows out on stage as much as possible,” he adds. “It enhances their experience.”

This summer, of course, things were a bit different. “We are embracing the virtual environment,” says Reed. “We are trying to deliver our mission in a different way” with the Music Academy Remote Learning Institute (MARLI). Each of this year’s 134 fellows—based all over the world—got state-of-the-art technical equipment that allowed them to participate in a four-week curriculum of seminars and one-on-one teaching with faculty members who were also geographically scattered. Then, during a two-week creative extension, fellows were invited to “take their training and put it into action,” says Reed, by creating content, pitching new project ideas, and auditioning for 10 days of training with the London Symphony Orchestra, which has partnered with the Academy for several years.

Meanwhile the community was also able to enjoy virtual picnic concerts, layered orchestral performances, and other special events at a daily online concert hall. The popular compeer program, which pairs a fellow with a local resident, went virtual as well but remained a crucial element of the summer festival. “The compeer program creates a relationship,” says Reed. “There’s no better way to learn about the Academy’s impact or the life of a classical musician than by being a compeer.”

MARLI is just the latest development in the evolution of the Music Academy, which was first proposed at a luncheon meeting of the Montecito Country Club in September 1946. The idea of a training ground for talented young musicians in the West proved popular, and the first summer session, in June 1947, welcomed students from California, Texas, Utah, and Vancouver, Canada, to the classes, which were held at Cate School.

In 1951, the Music Academy acquired Miraflores, originally built in 1909 as the Santa Barbara Country Club and converted in 1915 to an elegant Spanish revival residence for the Jefferson family. By 1952, the mansion and its grounds had been adapted for teaching and practice studios and concerts, though the students lived at Cate School.

The star-studded faculty in the early years ranged from Lehman, who pioneered the idea of master classes here, to composers Darius Milhaud and Arnold Schoenberg and pianist Gregor Piatigorsky, among many others. Over the decades, both the vocal and instrumental programs earned international attention that was enhanced by former students who went on to become acclaimed opera and concert performers.

There were many notable landmarks—the decision to become a full scholarship institution in the 1990s, the arrival of Marilyn Horne to head the voice program in 1997, the addition of Claeyssens Hall in 1993 for studios, the superb acoustic and architectural renovation of Hahn Hall in 2008, the addition of the Luria Education Center in 2012, and long-term partnerships with the New York Philharmonic and the London Symphony Orchestra.

During the last 10 years, the emphasis on interaction with the community has continued to grow. “You have to be relentless to get off campus,” says Reed, “out to Santa Barbara and Goleta.“ Community access tickets—at just $10—allow everyone to come and hear world-class musicians. Large public concerts at the Santa Barbara Bowl, which once occurred at five-year anniversaries, now are part of the city’s summer traditions.

In 2021 the summer festival is slated to return to a more traditional format. This year’s fellows are already invited back to the campus, and live classes and concerts are anticipated. “But there is no turning back,” insists Reed. “This is a new platform. We’re finding a solution that has given us something to be excited about. A new step in how we communicate. MARLI demonstrates our adaptability. That’s a silver lining.”

See the story in our digital magazine

Social Studies

Sculptures by Karon Davis reflect the zeitgeist

Sculptures by Karon Davis reflect the zeitgeist

Written by L.D Porter

The devastating 2017 Thomas Fire that forced artist Karon Davis to evacuate from her Ojai home prompted the creation of one of her most compelling life-size plaster sculptures, Noah and his Ark. Currently on view at U.C. Santa Barbara’s Art, Design & Architecture Museum until December, the work depicts a woman and child seated in a rowboat filled with personal objects—perhaps their only remaining possessions—guided by a man attempting to navigate though thigh-high water. The piece is part of Davis’s Muddy Water series, a title that refers to “Muddy waters caused by natural disasters or manmade systems that fail us,” according to the artist.

Contemporary collector (and seasonal Santa Barbara resident) Beth Rudin DeWoody, who owns several works by Davis—including Noah and his Ark—says “Karon’s work always has the sense of now. Reflections of the black community with so much power. I feel privileged to have these works and to know such an amazing woman.”

Originally from Reno, Nevada, Davis studied theater at Spelman College and cinema at the University of Southern California before pivoting to sculpture. Her first solo show was at L.A.’s Underground Museum, which she cofounded with her late husband, Noah Davis, in 2012. Davis’s work is highly acclaimed and widely exhibited. She is represented by L.A.’s Wilding Cran Gallery (wildingcran.com).

See the story in our digital magazine

Making Waves

A new monograph celebrates the art of Hank Pitcher

A new monograph celebrates the art of Hank Pitcher

Written by L.D. Porter

For nearly five decades, Hank Pitcher has painted what he knows best: Santa Barbara and the people who inhabit it. Now his gallery of 20 years, Sullivan Goss—An American Gallery, has produced an impressive monograph (Hank Pitcher, available at Upstairs at Pierre LaFond) packed with vibrant images accompanied by thoughtful essays penned by scholars, colleagues, and friends. It’s a well-deserved paean to the artist’s oeuvre.

Arriving in Santa Barbara in 1951 at the age of 2, Pitcher grew up in Isla Vista (he was a star fullback at San Marcos High School) and studied art and literature at U.C. Santa Barbara’s newly minted College of Creative Studies (he’s been a core faculty member there since 1971). Fully embracing the California lifestyle, Pitcher became an avid surfer and created the infamous—and still extant—logo for Mr. Zogs surfboard Sex Wax brand. Only love could convince him to leave Santa Barbara, and it did, in 1980, when he moved to New York City to follow his soon-to-be wife, Susan, a fashion trendsetter. They returned to California a year later, bringing memories of the Mudd Club, punk music, and the thriving art world scene.

As an artist, Pitcher has always been true to his vision. Resisting art world trends, his paintings are straightforward and devoid of irony or sentimentality; from his totemic surfboard portraits, sweeping Gaviota Coast landscapes, surfers captured at the shore, to his stately serene nudes—Pitcher distills his subject matter to its essence and makes every brushstroke count. It's a fearless approach, and the work's lack of pretension belies the masterful technique required to produce it.

See the story in our digital magazine

Rustic California Modern Redefined

Architect William Hefner and interior designer Kazuko Hoshino find paradise in Montecito

Architect William Hefner and interior designer Kazuko Hoshino find paradise in Montecito

Written by Cathy Whitlock | Photographs by Richard Powers

It’s often said that doctors make the worst patients, and perhaps the same holds true for architects and designers who become their own clients.

Architect William Hefner and his interior designer wife, Kazuko Hoshino, found this to be the case when they built a second home in Montecito’s Romero Canyon. Nestled on a one-acre lot filled with oak trees, picture-perfect mountain views (that include overgrown vegetation run amok), and roots dating back to the 1930s, the modern L-shaped home took some 10 years of planning, as indecision and house-changing discoveries came into play. “My wife and I are the worst clients, and we’re constantly changing our minds, always prioritizing our client’s work, and as a result, the progress would stop,” reflects Hefner, whose firm Studio William Hefner is based in Los Angeles and Montecito.

Inspired by the work of Arts and Crafts architect Bernard Maybeck and the couple’s favorite haunt, the San Ysidro Ranch, the California native says, “We planned it as a vacation home and really didn’t want it to feel like a grown-up house. We wanted it to be more like the San Ysidro Ranch compound where you sleep in one building and have your breakfast in another.” The couple’s goal was to make the house “simple in its tone,” eschewing the Spanish Colonial look that is so prevalent in Montecito.

Digging for the pool and foundation led to a discovery that changed the entire exterior. The multidisciplined architect notes, “We found a bunch of native stone and instead of hauling it off, we put it on the exterior. I wanted it to have the feel of a hunting lodge not for hunting, and the stone brings a lot of character to the site, which is the most enduring thing about the house. One of the things that is so special is we didn’t want it to feel so brand-spanking new, and the stone made it feel older.”

This resulted in three stone-and-wood buildings connected by breezeways with a stand-alone pool house that does double duty as a guest house. Designed on one level with an open floor plan that welcomes indoor/outdoor living, the house also features a game room to accommodate their 11-year-old son’s interests. “And because there were seven really beautiful 200-year-old oak trees we wanted to keep, it’s kind of like a puzzle where we had to break the house into pieces and sprinkle it in between the trees.”

Working with his wife (who brings a Japanese sensibility to the rustic California-modern interiors), the pair wanted the family retreat “under-finished,” where minimalism is the order of the day. Devoid of clutter, art-filled walls, and coffee-table collections, comfortable midcentury-style furnishings and a soft color palette (neutral shades mixed with blue indigo and sage green make an appearance) make up the decor. “My wife’s family lives in Tokyo, and we go once a year, spending two to three days in traditional Japanese inns. We loved the rustic settings and the combination of indigo blues and natural woods, so we tried to carry some of those colors throughout the house. Being in the business, we notice everything in a room, so we made it deliberately bare and, as a result, more relaxing to us.”

Adding a touch of pedigree, Hoshino scoured the Internet for vintage light fixtures that dot the various rooms of the house. “My wife would scroll through the Internet every night for three years for furnishings,” Hefner notes. “She found great European, Scandinavian, and Italian light fixtures for all the rooms, pieces from the 1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s, mostly in brass.” A vintage pool table and outdoor furniture along with leather and brass pulls are just a few of the items that, in the architect’s words, “don’t make it feel so 2018.”

Living in Montecito means taking advantage of the sunny, temperate climate and unparalleled landscape. “The house is a nice contrast for us, as we live in the middle of Los Angeles (Hancock Park), and this feels like the country,” Hefner says. “The compound is shaped to maximize the garden, and there are so many places to go and sit outside during different times of the day. You can have breakfast under the trees and enjoy views of the mountains.” They also enhanced the property with four olive trees, a cook’s garden near an orchard of fruit trees, and a path for their son’s go-carts. And in a move that appalled his firm’s landscape designers, the architect kept the original yucca plants. “They didn’t want me to use them as they are freeway plants,” he muses. “They add character and have this sort of Jurassic Park feel to them.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

The Fine Print

When Portia De Rossi left acting and Los Angeles behind, she focused her energy on life in Montecito and pursuing her new business, General Public, making art more accessible for everyone

When Portia De Rossi left acting and Los Angeles behind, she focused her energy on life in Montecito and pursuing her new business, General Public, making art more accessible for everyone

Written by Christine Lennon | Photographs by Dewey Nicks

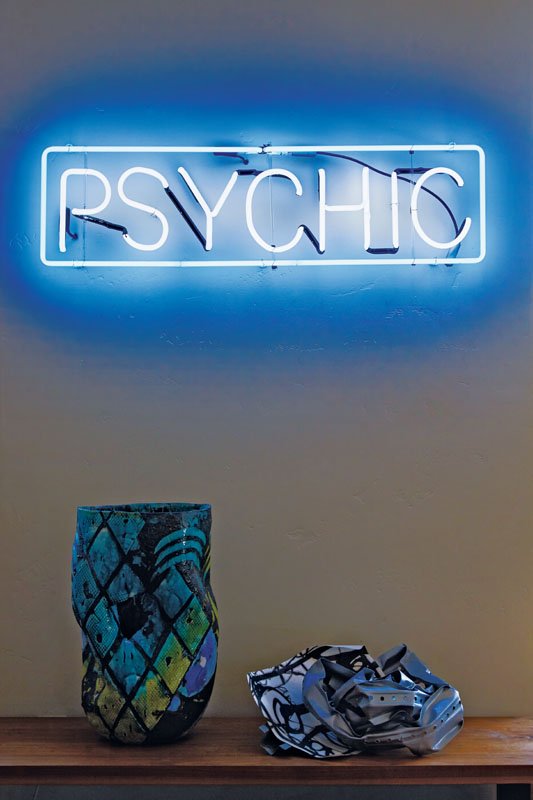

It’s clear that something interesting is happening inside a renovated factory building in downtown Carpinteria, even from the sidewalk. The exterior, which has been spruced up with a fresh coat of greige paint and black metal barn lights, is spare and signless like a hidden art gallery. But if you listen carefully, you can hear the electronic hum of large equipment inside. It could be a factory, an artist’s studio, or a modern technology hub.

Or, as the current tenant Portia de Rossi will explain, it’s all three of those concepts at once. The building is the new main office and manufacturing center of General Public—the company that she founded with her brother, Michael Rogers. They’re using 3D printing technology to produce textured art prints called synographs, which are available through the Restoration Hardware website.

“There’s a huge gap in the market between fine art and decorative art,” says de Rossi, who raises her voice to be heard over the noise of the room-size scanners and printers. The framing team is stretching canvases onto wooden frames in another section of the 20,000-square-foot space with unfinished concrete floors and exposed rafters. “If you’re buying art on a budget, you just end up with black squiggles on a piece of paper,” she says. “People know good art and composition, truly, but they don’t trust their instincts. And almost all original art is still very expensive. The whole market can be very difficult.”

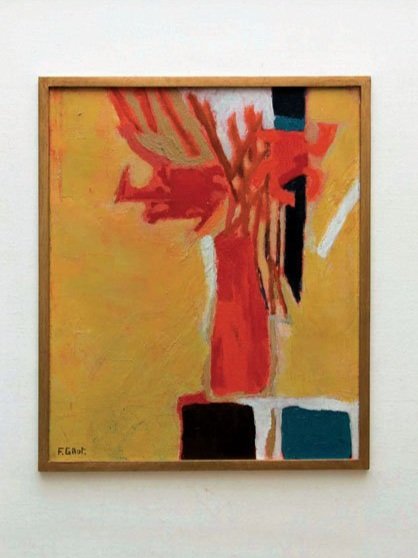

The 47-year-old former actress seems entirely in her element, discussing how many tiff files the scanner has to produce to replicate the look and feel of thick paint on a canvas, conveying the “information you get from a brushstroke” in a way that traditional prints cannot. “It’s like we’re creating a topographical map,” she says, clearly delighted that she and her tech team devised a way to create an entirely new category in the art world. It’s a licensing model. Artists submit their work to the site for consideration. A team of curators chooses which artist they work with, who then send in their paintings to be scanned and reproduced. The work is returned in a couple of weeks like nothing ever happened. Artists are free to sell and show their work, and they receive royalties based on sales of the paintings, which de Rossi calls “mailbox money.” Their best-selling artist has received $90,000 in royalties.

“This is all technology that existed before, but our team found a way for the software—between the scanner and the printer—to communicate in a way that they hadn’t before. Essentially, it’s just sprayed ink on a canvas, but we just tricked the printer into going over the same surface over and over. When we started the company, the thought was, If we can 3D-print a table, how can we not 3D-print a painting?”

“Artists, sculptors, musicians, actors are all expressing their experience of life, and the beauty of doing that is that you get to connect with other people, and other people understand your perspective. Being able to share your work is everything.”

De Rossi and her wife, beloved talk show host Ellen DeGeneres, have been fixtures in the Santa Barbara area since 2005, when they bought their first in a series of homes in Montecito, on Ashley Road. De Rossi, a native Australian, was drawn to the horse-country lifestyle and the casual small-town atmosphere, whereas DeGeneres had discovered the city when she performed her stand-up comedy at The Arlington Theatre and dreamed of owning a house here. Busy work schedules in Los Angeles meant that the couple—who have become well-known for their exquisite taste and for buying and renovating architecturally interesting homes—was torn about how to split their time. Just last year, they worked out a plan: De Rossi is at their home in Montecito nearly full-time, working at General Public, and DeGeneres is there Wednesday night to Monday morning.

The couple has developed a shorthand for designing their homes. De Rossi is the expert with light and space, following her instincts about how to organize furniture in a room, or how to make a floor plan more conducive to living. “But don’t ask me to pick out a textile,” she laughs. “And Ellen is the one who’s in charge of furniture.”

DeGeneres is an informed collector of midcentury French furniture and lighting from designers such as Jean Prouvé and Jean Royère. She has bought and renovated dozens of homes in her lifetime, hiring a top team of interior consultants and landscape architects like Clements Design, Cliff Fong, and Mark Rios to collaborate on restorations. In the process of decorating and living in a number of houses over the years, de Rossi came to understand how challenging it can be to pull together an art collection that reflects one’s style and taste, especially on a budget. When she decided to stop acting back in 2017, she was searching for a new project, and the dots started to connect. She approached her brother, Michael, who she describes as a “tech guy,” with the inkling of an idea. And they took the leap together.

Now, her refined but edgy aesthetic is writ large over the General Public office space. De Rossi has a Prouvé desk in her personal office, mixed with a rust-colored velvet RH sofa, some shearling upholstered chairs, and a Royère floor lamp. She commissioned Nicholas Tramontin—a General Public artist in residence—to create a dynamic mural on a low concrete wall, which he created on a skateboard with dozens of cans of spray paint. And her SAG award is affixed to the top of a $1 million printer.

By any measure, the life de Rossi and DeGeneres have built for themselves seems to check all of the right boxes. De Rossi walks across the street to ride two of her retired horses every day at lunch. She brings her dogs to the office and takes regular business meetings on the beach, which is just a block away. “I wanted to have a workplace where everyone was happy. And we have that here. We can see the ocean from our front door,” she says.

“It’s small-town living, but it’s so sophisticated. And we have a great community of friends,” says de Rossi, who is a regular at Field + Fort, the new cafe and shop in Summerland owned by their friend and designer Kyle Irwin, who is working with the couple on another house project. And every day, she does what she loves: being in nature and “creating a platform for painters to put their work out into

the world.

“Artists, sculptors, musicians, actors are all expressing their experience of life, and the beauty of doing that is that you get to connect with other people, and other people understand your perspective. Being able to share your work is everything.

“That’s what art does. It elevates people. It connects people,” she continues. “And it’s really a lovely thing that we get to introduce all of these new artists—from Belgium, Italy, Canada, or wherever—and I get to share those folks with people who live in Carpinteria. And then all over the country.” •

Hair by Laini Reeves. Makeup by Heather Currie for Cloutier Remix. Styled by Kellen Richards.

See the story in our digital magazine

Off Duty

Designer Isabelle Dahlin and chef Brandon Boudet unwind in Ojai

Designer Isabelle Dahlin and chef Brandon Boudet unwind in Ojai

Written by Jennifer Blaise Kramer | Photographs by Erin Kunkel

Swedish-born Isabelle Dahlin has mastered the art of a casual, boho lifestyle, as seen through her brand, deKor. Her Los Angeles and Ojai design stores are brimming with carefree pieces—think swinging rattan chairs, cool textiles, and transporting candles—and her New York City outpost, which debuted last fall, is home to three floors of inviting style channeling the best of Sweden, France, and California. Her signature global approach and warm, friendly, irreverent way of living inspired the authors of Hygge & West Home: Design for a Cozy Life (2018, Chronicle Books) to include her and husband Brandon Boudet’s Ojai home in their pages. The couple’s 680-square-foot weekend getaway is reminiscent of a small Swedish farmhouse—down to the blue front door and backyard sauna (a Swedish staple that Dahlin feels life isn’t worth living without). Boudet—a chef at multiple restaurants, including MiniBar in L.A. and soon-to-be Little Dom’s Seafood in Carpinteria—continues to cook while off duty, he just does it outside. “He loves the outdoor kitchen because everyone can be in the same area, and when it’s hot, the pool is just a few feet away,” she says.

While their inside kitchen is charming with restaurant-salvaged appliances and cool graphic tile, most of the dinner action happens out back on either the custom Santa Maria grill or the beehive pizza oven. That’s where Boudet whips up anything from whole grilled Vermillion snapper with garden-grown citrus and rosemary to a Spanish tortilla with fresh eggs from their chickens. A wooden outdoor bar and dining room is cozied up to a fireplace and one of Dahlin’s must-have hanging chairs for swinging into the pink moment with friends.

Impulse entertaining suits the couple, as friends frequently pop by for whatever theme the hosts have chosen. Recent evenings have featured steak frites, salad, and chocolate mousse during a screening of Midnight in Paris to pizza and karaoke to grilled Greek food eaten from the pool where there’s a floating bar of champagne bottles in buckets. “Our parties are usually last-minute decisions based mainly on the reason that we don’t feel like leaving the house,” Dahlin says. “Ojai is such a respite for us.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

Renaissance Man

Henry Lenny makes and remakes Santa Barbara’s architectural face

Henry Lenny makes and remakes Santa Barbara’s architectural face

Written by Josef Woodard | Photographs by Dewey Nicks | Drawings by Henry Lenny

It is fair to say that the seasoned architect Henry Lenny has played an instrumental role in making and maintaining Santa Barbara’s architectural heritage and landscape. His careful work has gone into restorations of El Paseo in the mid-1980s and the heralded, major redo of the El Encanto—that beacon on the hill—from 2001 until it reopened after its renovation in 2013. Also on his résumé are projects at the Presidio and the grand 1929-vintage courthouse—both hallmarks of Santa Barbara’s cultural and civic identity—along with a long list of residential and hospitality projects and a client list including Ty Warner, Fess Parker, the late El Encanto owner Erik Friden, among countless others.

Lenny’s work has taken root in the 805, in San Clemente, and other parts of Southern California; in Las Vegas; and globally in China, Abu Dhabi, and soon in London.

But when speaking about his work, as he did one afternoon in the living room-turned-studio of his Carpinteria home—with a small avocado orchard in the backyard and his living space speckled with objets d’art from his travels—Lenny’s thoughts and references extend beyond his own doings. Well-studied and well-traveled, Lenny pointed to examples of other architects’ work in the city he has called home for 30-plus years. Those architectural riches include Montecito houses designed by Bernard Maybeck, Bertram Goodhue, Roland Coates, Addison Mizner, and, of course, George Washington Smith—the guru and spearhead of the Spanish Colonial Revival style. “The whole city is a fascinating history book,” says Lenny. “It’s a museum of architecture. You’ll find everything here.”

Hailing from Guadalajara, Mexico, where he studied at the Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara school of architecture, Lenny made his way to Santa Barbara in 1983, a defining moment of change and focus. “Even though I was trained and educated by professors who were modernists,” he says, “I came to Santa Barbara, and my style had to change. But I feel quite comfortable working in any style. I have always been a student of the history of architecture. The principles are all the same. I can do everything from Chinese architecture to Spanish to very modern buildings.”

As a longtime member of the Historic Landmarks Commission, Lenny also coauthored the guidelines for the “Pueblo Viejo” style sheet that—although controversial in some quarters—has turned Santa Barbara into a model of a unified architectural city plan, as led by the Architectural Board of Review and other governing bodies.

Whereas some architects have been frustrated by ABR demands, Lenny admits, “I never really have a problem getting anything approved, because I understand and I present things that I know are compatible with Santa Barbara. I want to make sure that my work does not destroy the character-defining principles of what Santa Barbara started out with. After the 1925 earthquake, a lot of architects got together and created a vision. The vision was to create a wonderful village by the sea.”

He needs no coaxing to wax eloquent about his adopted hometown and its special character. As he points out, “Charles Moore [the famed architect Lenny has collaborated with] used to say, ‘Santa Barbara reminds me of a place that I had never been to before.’ Santa Barbara, I can say, is a dream that you experience while you’re awake. And that experience must be preserved long after I’m gone and hopefully through generations in the future.”

Designer Tammy Hughes, along with her partner/husband, Kim, have known, worked with, and admired Lenny for many years. Among the projects they have called on Lenny to collaborate on were a “Tuscan palazzo”-style house in Hope Ranch, a Mediterranean beachfront house on the Mesa, and a current ambitious renovation of a century-old house with Lockwood DeForest landscaping on Ortega Ridge.

Tammy refers to Lenny as being among “the last of the dreamers,” she says. “We’ve moved into such a technological age, and even the great architects have moved into doing a lot of their work digitally. He can draw it out on a cocktail napkin in five minutes, a sketch that can blow your mind. It’s like breathing for him. He’s an artist before an architect in my mind. He has such a good sense of scale and composition, and that comes from his painting.”

Referring to Lenny’s deep grasp of architectural principles mixed with an innately creative spirit, she adds that “when you know the rules as well as he does, then you can bend them a little bit. He understands classical architecture like no one, and yet he likes to riff of them, while always making sure you keep the details.”

Lenny was once part of a large firm with 39 employees but felt creatively hampered by the group’s corporate nature. He pared down to just a small firm, now with an office by Cabrillo Boulevard. But he likes to work in the quiet and privacy of his home studio, where, on this afternoon, the larger drawing board held a scrolling, highly detailed painting/rendering of a massive multiuse project in progress in Fort Apache, near Las Vegas.

Favoring handmade fixtures and detailing (“I’m not a fan of selecting things off the shelf,” he says), Lenny also relies on old-school, hands-on, and nondigital design work. “In every single project that I do,” Lenny asserts, “I start out with a painting or a rendering. From there, I develop it more and more. I do everything to scale, meaning the dimensions are correct. That makes it easier for the people who do the construction documents to scale it—to scan it, put in a program, and it gives them the dimensions.”

Paper counts for much in a Lenny project: “I do little projects and big projects,” he shrugs while pointing to the epic Fort Apache project filling his work table. “That’s just a bigger piece of paper that I’m working with.”

As for 2020, Lenny comments, “This feels like the best period of my life. I’m 72. I’ll never retire. I’m still painting. I’m still designing. I was too confused when I was 30. You know how it is with us—the first years of our life, we spend gathering knowledge, and at some point in time, we become so cocky that we say, ‘I think I now know everything there is to know about everything.’

“Years later, you realize that you know nothing. You absolutely know nothing. That’s when knowledge turns to wisdom, when you become a wise man, you finally realize who you are, what you are, and where you stand in the world.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

A New Era

Celebrating 100 years of EL Cielito—Montecito’s “Little Heaven”

Celebrating 100 years of EL Cielito—Montecito’s “Little Heaven”

Written by Joan Tapper | Photographs by Dewey Nicks

El Cielito—one of Montecito’s great estates—is celebrating a centennial…and welcoming the decade with new stewards for its future. It was in 1920 that painter Doug Parshall commissioned famed architect George Washington Smith to transform the late-19th-century home on his property into an Andalusian-style residence with white plaster walls and a red-tiled roof. Smith graced the house with a classic rectangular entry, crowning the doorway with a wrought-iron balcony. He oriented the floor plan along four axes to take advantage of the views—ocean to the south, gardens on the east and west, and a grand oval driveway in front—inspiring Parshall to name the house Cuatros Vistos (“Four Views”). Inside, arched doorways, beamed ceilings, and terra-cotta floors carried out the Spanish country house theme.

Meanwhile, Dutch horticulturalist Peter Riedel landscaped the extensive grounds, planting exotic and specimen trees, siting an octagonal tiled fountain to one side, enclosing a rose garden with hedges, and, notably, designing two exquisite reflecting pools aligned with the front door that rolled out into the garden.

Over the decades, the estate changed hands and names—and portions of the property were sold, leaving a still generous four acres around the residence, which also underwent miscellaneous alterations.

About a dozen years ago, the then-owners took on the challenge of a serious renovation and addition that would adapt the home to 21st-century living. Working with Santa Barbara architect Don Nulty, who has overseen numerous historical restorations, they upgraded electrical and other systems, added a family room and space for guests, improved the traffic flow through Smith’s rooms, and updated and enlarged the kitchen and baths, all the while respecting and celebrating the original architecture and its intimate scale. The goal was to make it look—inside and out—as though the house had always been this way.

An arched portico with a glassed-in gallery above seamlessly married the old and new sections of the home. Terra-cotta floors were restored and duplicated in the new rooms; additional cabinets in the kitchen and pantry were built to mirror the originals, as were fireplace grates, decorative tiles, and wrought-iron sconces.

The garden was enhanced as well by landscape architect Dennis Hickok, who, among other touches, installed a new “hot” garden of succulents around towering dracaenas and a monkey puzzle tree.

Today the grounds are gorgeously lush, nurtured once again by recent rains. Ivy extends across both wings of the home, which are united with the grace and elegance of a century ago. Embraced by its new owners, El Cielito stands magnificent and ready for its next hundred years. •

See the story in our digital magazine

A Passionate Pursuit

Collectors Sandi and Bill Nicholson celebrate women who make art

MARTHA GRAHAM 25, 1931, photograph, 12 x 17 in. Imogen Cunningham (1883-1976).

Collectors Sandi and Bill Nicholson celebrate women who make art

Written by L.D. Porter | Photography courtesy of Women Who Dared

Like most art collectors, the Nicholsons—Sandi and Bill—are interesting people. What makes them fascinating is the nature of their collection: All of the work is by women artists.