Rustic California Modern Redefined

Architect William Hefner and interior designer Kazuko Hoshino find paradise in Montecito

Architect William Hefner and interior designer Kazuko Hoshino find paradise in Montecito

Written by Cathy Whitlock | Photographs by Richard Powers

It’s often said that doctors make the worst patients, and perhaps the same holds true for architects and designers who become their own clients.

Architect William Hefner and his interior designer wife, Kazuko Hoshino, found this to be the case when they built a second home in Montecito’s Romero Canyon. Nestled on a one-acre lot filled with oak trees, picture-perfect mountain views (that include overgrown vegetation run amok), and roots dating back to the 1930s, the modern L-shaped home took some 10 years of planning, as indecision and house-changing discoveries came into play. “My wife and I are the worst clients, and we’re constantly changing our minds, always prioritizing our client’s work, and as a result, the progress would stop,” reflects Hefner, whose firm Studio William Hefner is based in Los Angeles and Montecito.

Inspired by the work of Arts and Crafts architect Bernard Maybeck and the couple’s favorite haunt, the San Ysidro Ranch, the California native says, “We planned it as a vacation home and really didn’t want it to feel like a grown-up house. We wanted it to be more like the San Ysidro Ranch compound where you sleep in one building and have your breakfast in another.” The couple’s goal was to make the house “simple in its tone,” eschewing the Spanish Colonial look that is so prevalent in Montecito.

Digging for the pool and foundation led to a discovery that changed the entire exterior. The multidisciplined architect notes, “We found a bunch of native stone and instead of hauling it off, we put it on the exterior. I wanted it to have the feel of a hunting lodge not for hunting, and the stone brings a lot of character to the site, which is the most enduring thing about the house. One of the things that is so special is we didn’t want it to feel so brand-spanking new, and the stone made it feel older.”

This resulted in three stone-and-wood buildings connected by breezeways with a stand-alone pool house that does double duty as a guest house. Designed on one level with an open floor plan that welcomes indoor/outdoor living, the house also features a game room to accommodate their 11-year-old son’s interests. “And because there were seven really beautiful 200-year-old oak trees we wanted to keep, it’s kind of like a puzzle where we had to break the house into pieces and sprinkle it in between the trees.”

Working with his wife (who brings a Japanese sensibility to the rustic California-modern interiors), the pair wanted the family retreat “under-finished,” where minimalism is the order of the day. Devoid of clutter, art-filled walls, and coffee-table collections, comfortable midcentury-style furnishings and a soft color palette (neutral shades mixed with blue indigo and sage green make an appearance) make up the decor. “My wife’s family lives in Tokyo, and we go once a year, spending two to three days in traditional Japanese inns. We loved the rustic settings and the combination of indigo blues and natural woods, so we tried to carry some of those colors throughout the house. Being in the business, we notice everything in a room, so we made it deliberately bare and, as a result, more relaxing to us.”

Adding a touch of pedigree, Hoshino scoured the Internet for vintage light fixtures that dot the various rooms of the house. “My wife would scroll through the Internet every night for three years for furnishings,” Hefner notes. “She found great European, Scandinavian, and Italian light fixtures for all the rooms, pieces from the 1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s, mostly in brass.” A vintage pool table and outdoor furniture along with leather and brass pulls are just a few of the items that, in the architect’s words, “don’t make it feel so 2018.”

Living in Montecito means taking advantage of the sunny, temperate climate and unparalleled landscape. “The house is a nice contrast for us, as we live in the middle of Los Angeles (Hancock Park), and this feels like the country,” Hefner says. “The compound is shaped to maximize the garden, and there are so many places to go and sit outside during different times of the day. You can have breakfast under the trees and enjoy views of the mountains.” They also enhanced the property with four olive trees, a cook’s garden near an orchard of fruit trees, and a path for their son’s go-carts. And in a move that appalled his firm’s landscape designers, the architect kept the original yucca plants. “They didn’t want me to use them as they are freeway plants,” he muses. “They add character and have this sort of Jurassic Park feel to them.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

The Fine Print

When Portia De Rossi left acting and Los Angeles behind, she focused her energy on life in Montecito and pursuing her new business, General Public, making art more accessible for everyone

When Portia De Rossi left acting and Los Angeles behind, she focused her energy on life in Montecito and pursuing her new business, General Public, making art more accessible for everyone

Written by Christine Lennon | Photographs by Dewey Nicks

It’s clear that something interesting is happening inside a renovated factory building in downtown Carpinteria, even from the sidewalk. The exterior, which has been spruced up with a fresh coat of greige paint and black metal barn lights, is spare and signless like a hidden art gallery. But if you listen carefully, you can hear the electronic hum of large equipment inside. It could be a factory, an artist’s studio, or a modern technology hub.

Or, as the current tenant Portia de Rossi will explain, it’s all three of those concepts at once. The building is the new main office and manufacturing center of General Public—the company that she founded with her brother, Michael Rogers. They’re using 3D printing technology to produce textured art prints called synographs, which are available through the Restoration Hardware website.

“There’s a huge gap in the market between fine art and decorative art,” says de Rossi, who raises her voice to be heard over the noise of the room-size scanners and printers. The framing team is stretching canvases onto wooden frames in another section of the 20,000-square-foot space with unfinished concrete floors and exposed rafters. “If you’re buying art on a budget, you just end up with black squiggles on a piece of paper,” she says. “People know good art and composition, truly, but they don’t trust their instincts. And almost all original art is still very expensive. The whole market can be very difficult.”

The 47-year-old former actress seems entirely in her element, discussing how many tiff files the scanner has to produce to replicate the look and feel of thick paint on a canvas, conveying the “information you get from a brushstroke” in a way that traditional prints cannot. “It’s like we’re creating a topographical map,” she says, clearly delighted that she and her tech team devised a way to create an entirely new category in the art world. It’s a licensing model. Artists submit their work to the site for consideration. A team of curators chooses which artist they work with, who then send in their paintings to be scanned and reproduced. The work is returned in a couple of weeks like nothing ever happened. Artists are free to sell and show their work, and they receive royalties based on sales of the paintings, which de Rossi calls “mailbox money.” Their best-selling artist has received $90,000 in royalties.

“This is all technology that existed before, but our team found a way for the software—between the scanner and the printer—to communicate in a way that they hadn’t before. Essentially, it’s just sprayed ink on a canvas, but we just tricked the printer into going over the same surface over and over. When we started the company, the thought was, If we can 3D-print a table, how can we not 3D-print a painting?”

“Artists, sculptors, musicians, actors are all expressing their experience of life, and the beauty of doing that is that you get to connect with other people, and other people understand your perspective. Being able to share your work is everything.”

De Rossi and her wife, beloved talk show host Ellen DeGeneres, have been fixtures in the Santa Barbara area since 2005, when they bought their first in a series of homes in Montecito, on Ashley Road. De Rossi, a native Australian, was drawn to the horse-country lifestyle and the casual small-town atmosphere, whereas DeGeneres had discovered the city when she performed her stand-up comedy at The Arlington Theatre and dreamed of owning a house here. Busy work schedules in Los Angeles meant that the couple—who have become well-known for their exquisite taste and for buying and renovating architecturally interesting homes—was torn about how to split their time. Just last year, they worked out a plan: De Rossi is at their home in Montecito nearly full-time, working at General Public, and DeGeneres is there Wednesday night to Monday morning.

The couple has developed a shorthand for designing their homes. De Rossi is the expert with light and space, following her instincts about how to organize furniture in a room, or how to make a floor plan more conducive to living. “But don’t ask me to pick out a textile,” she laughs. “And Ellen is the one who’s in charge of furniture.”

DeGeneres is an informed collector of midcentury French furniture and lighting from designers such as Jean Prouvé and Jean Royère. She has bought and renovated dozens of homes in her lifetime, hiring a top team of interior consultants and landscape architects like Clements Design, Cliff Fong, and Mark Rios to collaborate on restorations. In the process of decorating and living in a number of houses over the years, de Rossi came to understand how challenging it can be to pull together an art collection that reflects one’s style and taste, especially on a budget. When she decided to stop acting back in 2017, she was searching for a new project, and the dots started to connect. She approached her brother, Michael, who she describes as a “tech guy,” with the inkling of an idea. And they took the leap together.

Now, her refined but edgy aesthetic is writ large over the General Public office space. De Rossi has a Prouvé desk in her personal office, mixed with a rust-colored velvet RH sofa, some shearling upholstered chairs, and a Royère floor lamp. She commissioned Nicholas Tramontin—a General Public artist in residence—to create a dynamic mural on a low concrete wall, which he created on a skateboard with dozens of cans of spray paint. And her SAG award is affixed to the top of a $1 million printer.

By any measure, the life de Rossi and DeGeneres have built for themselves seems to check all of the right boxes. De Rossi walks across the street to ride two of her retired horses every day at lunch. She brings her dogs to the office and takes regular business meetings on the beach, which is just a block away. “I wanted to have a workplace where everyone was happy. And we have that here. We can see the ocean from our front door,” she says.

“It’s small-town living, but it’s so sophisticated. And we have a great community of friends,” says de Rossi, who is a regular at Field + Fort, the new cafe and shop in Summerland owned by their friend and designer Kyle Irwin, who is working with the couple on another house project. And every day, she does what she loves: being in nature and “creating a platform for painters to put their work out into

the world.

“Artists, sculptors, musicians, actors are all expressing their experience of life, and the beauty of doing that is that you get to connect with other people, and other people understand your perspective. Being able to share your work is everything.

“That’s what art does. It elevates people. It connects people,” she continues. “And it’s really a lovely thing that we get to introduce all of these new artists—from Belgium, Italy, Canada, or wherever—and I get to share those folks with people who live in Carpinteria. And then all over the country.” •

Hair by Laini Reeves. Makeup by Heather Currie for Cloutier Remix. Styled by Kellen Richards.

See the story in our digital magazine

Off Duty

Designer Isabelle Dahlin and chef Brandon Boudet unwind in Ojai

Designer Isabelle Dahlin and chef Brandon Boudet unwind in Ojai

Written by Jennifer Blaise Kramer | Photographs by Erin Kunkel

Swedish-born Isabelle Dahlin has mastered the art of a casual, boho lifestyle, as seen through her brand, deKor. Her Los Angeles and Ojai design stores are brimming with carefree pieces—think swinging rattan chairs, cool textiles, and transporting candles—and her New York City outpost, which debuted last fall, is home to three floors of inviting style channeling the best of Sweden, France, and California. Her signature global approach and warm, friendly, irreverent way of living inspired the authors of Hygge & West Home: Design for a Cozy Life (2018, Chronicle Books) to include her and husband Brandon Boudet’s Ojai home in their pages. The couple’s 680-square-foot weekend getaway is reminiscent of a small Swedish farmhouse—down to the blue front door and backyard sauna (a Swedish staple that Dahlin feels life isn’t worth living without). Boudet—a chef at multiple restaurants, including MiniBar in L.A. and soon-to-be Little Dom’s Seafood in Carpinteria—continues to cook while off duty, he just does it outside. “He loves the outdoor kitchen because everyone can be in the same area, and when it’s hot, the pool is just a few feet away,” she says.

While their inside kitchen is charming with restaurant-salvaged appliances and cool graphic tile, most of the dinner action happens out back on either the custom Santa Maria grill or the beehive pizza oven. That’s where Boudet whips up anything from whole grilled Vermillion snapper with garden-grown citrus and rosemary to a Spanish tortilla with fresh eggs from their chickens. A wooden outdoor bar and dining room is cozied up to a fireplace and one of Dahlin’s must-have hanging chairs for swinging into the pink moment with friends.

Impulse entertaining suits the couple, as friends frequently pop by for whatever theme the hosts have chosen. Recent evenings have featured steak frites, salad, and chocolate mousse during a screening of Midnight in Paris to pizza and karaoke to grilled Greek food eaten from the pool where there’s a floating bar of champagne bottles in buckets. “Our parties are usually last-minute decisions based mainly on the reason that we don’t feel like leaving the house,” Dahlin says. “Ojai is such a respite for us.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

Renaissance Man

Henry Lenny makes and remakes Santa Barbara’s architectural face

Henry Lenny makes and remakes Santa Barbara’s architectural face

Written by Josef Woodard | Photographs by Dewey Nicks | Drawings by Henry Lenny

It is fair to say that the seasoned architect Henry Lenny has played an instrumental role in making and maintaining Santa Barbara’s architectural heritage and landscape. His careful work has gone into restorations of El Paseo in the mid-1980s and the heralded, major redo of the El Encanto—that beacon on the hill—from 2001 until it reopened after its renovation in 2013. Also on his résumé are projects at the Presidio and the grand 1929-vintage courthouse—both hallmarks of Santa Barbara’s cultural and civic identity—along with a long list of residential and hospitality projects and a client list including Ty Warner, Fess Parker, the late El Encanto owner Erik Friden, among countless others.

Lenny’s work has taken root in the 805, in San Clemente, and other parts of Southern California; in Las Vegas; and globally in China, Abu Dhabi, and soon in London.

But when speaking about his work, as he did one afternoon in the living room-turned-studio of his Carpinteria home—with a small avocado orchard in the backyard and his living space speckled with objets d’art from his travels—Lenny’s thoughts and references extend beyond his own doings. Well-studied and well-traveled, Lenny pointed to examples of other architects’ work in the city he has called home for 30-plus years. Those architectural riches include Montecito houses designed by Bernard Maybeck, Bertram Goodhue, Roland Coates, Addison Mizner, and, of course, George Washington Smith—the guru and spearhead of the Spanish Colonial Revival style. “The whole city is a fascinating history book,” says Lenny. “It’s a museum of architecture. You’ll find everything here.”

Hailing from Guadalajara, Mexico, where he studied at the Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara school of architecture, Lenny made his way to Santa Barbara in 1983, a defining moment of change and focus. “Even though I was trained and educated by professors who were modernists,” he says, “I came to Santa Barbara, and my style had to change. But I feel quite comfortable working in any style. I have always been a student of the history of architecture. The principles are all the same. I can do everything from Chinese architecture to Spanish to very modern buildings.”

As a longtime member of the Historic Landmarks Commission, Lenny also coauthored the guidelines for the “Pueblo Viejo” style sheet that—although controversial in some quarters—has turned Santa Barbara into a model of a unified architectural city plan, as led by the Architectural Board of Review and other governing bodies.

Whereas some architects have been frustrated by ABR demands, Lenny admits, “I never really have a problem getting anything approved, because I understand and I present things that I know are compatible with Santa Barbara. I want to make sure that my work does not destroy the character-defining principles of what Santa Barbara started out with. After the 1925 earthquake, a lot of architects got together and created a vision. The vision was to create a wonderful village by the sea.”

He needs no coaxing to wax eloquent about his adopted hometown and its special character. As he points out, “Charles Moore [the famed architect Lenny has collaborated with] used to say, ‘Santa Barbara reminds me of a place that I had never been to before.’ Santa Barbara, I can say, is a dream that you experience while you’re awake. And that experience must be preserved long after I’m gone and hopefully through generations in the future.”

Designer Tammy Hughes, along with her partner/husband, Kim, have known, worked with, and admired Lenny for many years. Among the projects they have called on Lenny to collaborate on were a “Tuscan palazzo”-style house in Hope Ranch, a Mediterranean beachfront house on the Mesa, and a current ambitious renovation of a century-old house with Lockwood DeForest landscaping on Ortega Ridge.

Tammy refers to Lenny as being among “the last of the dreamers,” she says. “We’ve moved into such a technological age, and even the great architects have moved into doing a lot of their work digitally. He can draw it out on a cocktail napkin in five minutes, a sketch that can blow your mind. It’s like breathing for him. He’s an artist before an architect in my mind. He has such a good sense of scale and composition, and that comes from his painting.”

Referring to Lenny’s deep grasp of architectural principles mixed with an innately creative spirit, she adds that “when you know the rules as well as he does, then you can bend them a little bit. He understands classical architecture like no one, and yet he likes to riff of them, while always making sure you keep the details.”

Lenny was once part of a large firm with 39 employees but felt creatively hampered by the group’s corporate nature. He pared down to just a small firm, now with an office by Cabrillo Boulevard. But he likes to work in the quiet and privacy of his home studio, where, on this afternoon, the larger drawing board held a scrolling, highly detailed painting/rendering of a massive multiuse project in progress in Fort Apache, near Las Vegas.

Favoring handmade fixtures and detailing (“I’m not a fan of selecting things off the shelf,” he says), Lenny also relies on old-school, hands-on, and nondigital design work. “In every single project that I do,” Lenny asserts, “I start out with a painting or a rendering. From there, I develop it more and more. I do everything to scale, meaning the dimensions are correct. That makes it easier for the people who do the construction documents to scale it—to scan it, put in a program, and it gives them the dimensions.”

Paper counts for much in a Lenny project: “I do little projects and big projects,” he shrugs while pointing to the epic Fort Apache project filling his work table. “That’s just a bigger piece of paper that I’m working with.”

As for 2020, Lenny comments, “This feels like the best period of my life. I’m 72. I’ll never retire. I’m still painting. I’m still designing. I was too confused when I was 30. You know how it is with us—the first years of our life, we spend gathering knowledge, and at some point in time, we become so cocky that we say, ‘I think I now know everything there is to know about everything.’

“Years later, you realize that you know nothing. You absolutely know nothing. That’s when knowledge turns to wisdom, when you become a wise man, you finally realize who you are, what you are, and where you stand in the world.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

A New Era

Celebrating 100 years of EL Cielito—Montecito’s “Little Heaven”

Celebrating 100 years of EL Cielito—Montecito’s “Little Heaven”

Written by Joan Tapper | Photographs by Dewey Nicks

El Cielito—one of Montecito’s great estates—is celebrating a centennial…and welcoming the decade with new stewards for its future. It was in 1920 that painter Doug Parshall commissioned famed architect George Washington Smith to transform the late-19th-century home on his property into an Andalusian-style residence with white plaster walls and a red-tiled roof. Smith graced the house with a classic rectangular entry, crowning the doorway with a wrought-iron balcony. He oriented the floor plan along four axes to take advantage of the views—ocean to the south, gardens on the east and west, and a grand oval driveway in front—inspiring Parshall to name the house Cuatros Vistos (“Four Views”). Inside, arched doorways, beamed ceilings, and terra-cotta floors carried out the Spanish country house theme.

Meanwhile, Dutch horticulturalist Peter Riedel landscaped the extensive grounds, planting exotic and specimen trees, siting an octagonal tiled fountain to one side, enclosing a rose garden with hedges, and, notably, designing two exquisite reflecting pools aligned with the front door that rolled out into the garden.

Over the decades, the estate changed hands and names—and portions of the property were sold, leaving a still generous four acres around the residence, which also underwent miscellaneous alterations.

About a dozen years ago, the then-owners took on the challenge of a serious renovation and addition that would adapt the home to 21st-century living. Working with Santa Barbara architect Don Nulty, who has overseen numerous historical restorations, they upgraded electrical and other systems, added a family room and space for guests, improved the traffic flow through Smith’s rooms, and updated and enlarged the kitchen and baths, all the while respecting and celebrating the original architecture and its intimate scale. The goal was to make it look—inside and out—as though the house had always been this way.

An arched portico with a glassed-in gallery above seamlessly married the old and new sections of the home. Terra-cotta floors were restored and duplicated in the new rooms; additional cabinets in the kitchen and pantry were built to mirror the originals, as were fireplace grates, decorative tiles, and wrought-iron sconces.

The garden was enhanced as well by landscape architect Dennis Hickok, who, among other touches, installed a new “hot” garden of succulents around towering dracaenas and a monkey puzzle tree.

Today the grounds are gorgeously lush, nurtured once again by recent rains. Ivy extends across both wings of the home, which are united with the grace and elegance of a century ago. Embraced by its new owners, El Cielito stands magnificent and ready for its next hundred years. •

See the story in our digital magazine

A Passionate Pursuit

Collectors Sandi and Bill Nicholson celebrate women who make art

MARTHA GRAHAM 25, 1931, photograph, 12 x 17 in. Imogen Cunningham (1883-1976).

Collectors Sandi and Bill Nicholson celebrate women who make art

Written by L.D. Porter | Photography courtesy of Women Who Dared

Like most art collectors, the Nicholsons—Sandi and Bill—are interesting people. What makes them fascinating is the nature of their collection: All of the work is by women artists.

Twenty years ago, the couple—whose Montecito pied-à-terre is the historic Villa Solana—traveled across Europe and was shocked to discover that none of the many museums they visited featured art by women. “That’s what started it,” says Bill, “the curiosity of why women weren’t represented.” Since that time, the Nicholsons’ curiosity has led them to acquire 340 works—dating from 500 B.C. to the present—featuring female artists from all seven continents. Aptly named Women Who Dared, theirs is the largest privately held collection of its kind in the world.

“As we were putting the collection together, we realized that we really wanted to show the diversity of women,” explains Sandi. “We wanted to show art by women over time and through geography—internationally and throughout the ages.” The two traveled the world seeking art by women. They even went as far as Antarctica, where they acquired the work of contemporary photographer Zenobia Evans, who is a scientist living and working there. Sandi sums it up: “We love art, and we love collecting, and we love travel. And through this, we discovered artists whose voices had been suppressed or never heard. Now as the Women Who Dared collection, it’s become the chorus of global voices over more than 2,500 years.”

The Nicholsons became familiar with the myriad obstacles facing women artists, especially those born before the 20th century. “Women were treated almost as witches or adulteresses,” says Bill. “Men really worked hard to keep them out of the art establishment.” Jeremy Tessmer, of Santa Barbara’s Sullivan Goss—An American Gallery, observes that when the Nicholsons began forming their collection, artworks by women “were buried by time and the functional indifference of the art establishment.” The couple discovered that female artists who did receive support and encouragement were often married to an artist or worked as an artist’s assistant. Sandi notes that if women were given the opportunity to study and paint, “that became evident in the exposure of their works.”

Italian-born Ely De Vescovi (1910-1998) assisted Diego Rivera with several murals, and her discovery of modern fresco techniques in the 1930s was heralded by none other than The New York Times. De Vescovi moved to California in the 1940s and completed four mural panels in the acute mental wards of Los Angeles’s Sawtelle Psychiatric Hospital. She thereafter fell into obscurity until the late 1990s, when her nephew, the late gallery owner Robin Bagier of Ojai, exhibited her prolific and varied work. The Nicholsons own several pieces by De Vescovi, and Bill believes the artist’s later works—which became increasingly spiritual and visionary—resulted from her work at a veteran’s hospital with American soldiers returning from World War II.

Sandi especially loves the regal oil portrait of an African-American woman—simply titled Florence—by Lyla Vivian Marshall Harcoff (1883-1956). “That painting is very important,” says Sandi. “It shows pride, it shows dignity, it shows courage. During the Depression, Lyla—in order to financially survive—established herself as a furniture maker, which led to her making her own frames for the rest of her life.” Born in Indiana, Harcoff graduated from Purdue University in 1904 (one of eight women in a class of 218) and studied in Paris. She eventually moved to Santa Barbara, where she commissioned architect Lutah Maria Riggs to convert a carriage house into her studio/residence. The Santa Barbara Museum of Art gave her a solo show in 1949, and she was widely exhibited during her lifetime. Harcoff also completed several murals for the Works Progress Administration, including a mural at Santa Ynez Valley High School in 1936.

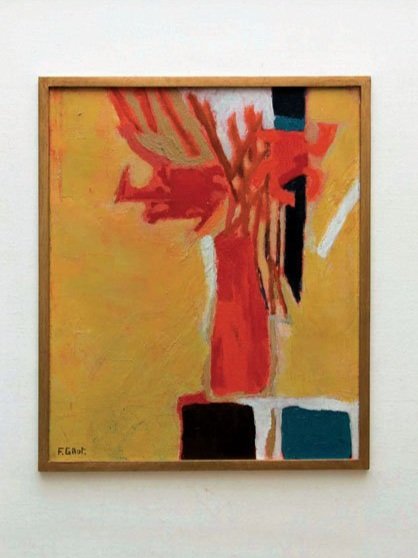

French-born Françoise Gilot (b. 1921) was an artist in her own right when she met Pablo Picasso, with whom she had a turbulent 10-year relationship. After their relationship ended, Picasso instructed all the art dealers he knew not to buy Gilot’s art. The Nicholsons acquired Gilot’s Flowers on a Yellow Field—a brightly colored, almost abstract oil painting for the collection; it is a dynamic example of the artist’s unique talent, as well as evidence of her determination. The Nicholsons have been in contact with Gilot (now 97), and hope to have a face-to-face meeting with the artist who defied Picasso.

The Nicholsons’ curiosity has led them to collect 340 works—dating from 500 B.C. to the present—featuring female artists from all seven continents.

Photography is a strong part of the collection, and American photographer Imogen Cunningham (1883-1976) is one of the standouts. An Oregon native, Cunningham was a contemporary of several noted male photographers who championed her work—Edward S. Curtis (for whom she worked), Edward Weston (who helped exhibit her work), and Ansel Adams (who invited her to join the faculty of the California School of Fine Arts). Cunningham’s photographs were published in Vanity Fair, where she worked from 1934 to 1936. Even so, the major awards she received—fellowship in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and a Guggenheim Fellowship—were granted in the last decade of her life. “Imogen Cunningham was really ahead of her time,” says Bill. “It is just within the last 10 years that photography by women has become recognized and appreciated in the market financially.” The collection’s luminous black-and-white portrait of modern dancer Martha Graham comes from a photo shoot that occurred on a hot afternoon in Santa Barbara. Graham—who spent her teenage years in Santa Barbara—met the photographer at a dinner party, and the photos were taken in front of Graham’s mother’s barn. Cunningham was 48, Graham was 37.

Among the collection’s abstract works is a striking geometric oil painting by Russian artist Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962). An active member of several avant-garde movements, Goncharova’s first major solo exhibition debuted in 1913. Moving to Paris in 1914, she produced costumes and set designs for Sergei Diaghilev’s famous Ballet Russes. She was included in the groundbreaking 1936 “Cubism and Abstract Art” show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and the museum has her work in its collection to this day. As evidence of her continuing importance in the art world, London’s Tate Modern museum mounted a Goncharova retrospective this year.

“As we were putting the collection together, we realized that we really wanted to show the diversity of women. We wanted to show art by women over time and through geography—internationally and throughout the ages.”

For the Nicholsons, every work in the collection has an important backstory to tell. As Sandi says, “We were first attracted to the artwork but soon realized the story or the narrative of the artist’s work and their lives resonated with us in a profound way. The artist’s perseverance, grit, and determination have been as powerful to us as the work itself.”

Understandably, the couple’s ultimate goal is to keep the collection together in an institution where “the girls” (as Sandi fondly calls them) can impact a large number of people on a regular basis. Bill adds, “We’d like to have people free to interact with the collection and hear the stories.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

Living with the Artists

A peek inside Jacquelyn Klein-Brown's contemporary art haven

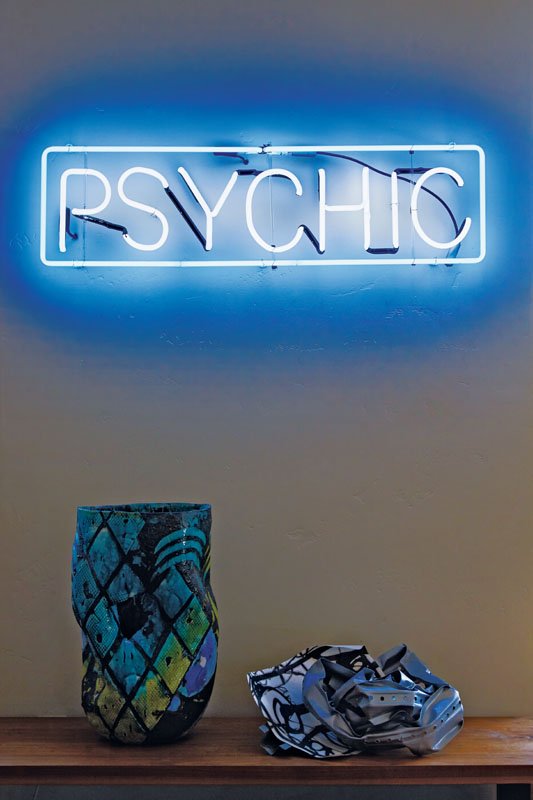

The outsized installations of arts collective Assume Vivid Astro Focus pack a vivid punch in a narrow corridor.

A peek inside Jacquelyn Klein-Brown's contemporary art haven

Written by Ninette Paloma | Photographs by Sam Frost

Stroll toward the entrance of Jacquelyn Klein-Brown’s inviting Montecito estate, and you’ll be greeted by artist Hayal Pozanti’s shimmering steel sculpture, its assertive curves and angles guiding you toward the front door. Inside, Anicka Yi’s seductive orchids and Marilyn Minter’s intrepid photography cut a striking image against midcentury modern furnishings—their lines and metaphors shifting with the afternoon sun. At every turn, the eye is pulled toward saturated canvases and outsize textiles, a sensorial playground of color and imagery with the petite and vivacious Klein-Brown at its epicenter.

“Most of the art in my house stimulates thoughts and emotions, often igniting happy, somber, or provocative feelings.” Klein-Brown explains with a laugh. “Depending on the time of day, you can see each piece in a different light. Sometimes I feel they’re a direct reflection of my mood—always speaking to me in a new way.”

Communicating with her sprawling collection is a daily occurrence for Klein-Brown; with paintings, photographs, sculptures, videos, and ceramics assembled throughout her home, the exchanges can feel boundless. “I can sit for hours with friends over a glass of wine contemplating the meaning of a photograph or installation,” she muses. “We’ve had some pretty incredible conversations in this house.”

For as long as she can remember, Klein-Brown has been contextualizing her world through the lens of contemporary art, inspired by her family’s unyielding passion for the avant-garde and emerging. As a young girl growing up in Houston, she would accompany her parents on art expeditions, shuffling between museums and galleries and attending notable exhibit openings across the globe. At the University of Texas at Austin, she majored in art history and slowly began to acquire a modest collection of her own, joining museum groups, exploring galleries, becoming acquainted with curators, and participating in artist talks wherever she traveled. By the time she moved to Santa Barbara in 2006, her life’s trajectory had become clear. “I had two priorities when I moved here,” she recalls. “Enroll the kids in a great school and join every art museum in town.”

Both the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara (MCASB) and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art came answering, offering Klein-Brown formidable seats on their respective boards. Through dedication and an extensive network of industry connections, Klein-Brown began earning a reputation as a trusted source for encouraging support and awareness in the visual arts—a role she approaches with a healthy balance of passion and pragmatism. “To work with someone who cultivates such a sense of fairness where everyone’s voice can be heard is a tremendous privilege,” says Abaseh Mirvali, former Executive Director of MCASB. “Jacquelyn fosters an environment of authentic generosity and she’s the first to lead with a giving spirit.”

On any given week, Klein-Brown makes it a point to open her home to art students and educational groups, offering insight and intimate anecdotes over the artists that live among her. Her face lights up as she recalls each moment of discovery—when a trip to an art fair led to an encounter with an artist that soon became a lifelong friend, or the feeling that bubbles over when she connects with a piece at first glance. “Every work that I’ve brought into my home feels very personal to me,” she explains. “I hope I am building a legacy that’ll last longer than any of us.” But refer to Klein-Brown as an avid collector, and she’ll be the first to point out that her egalitarian view of art aligns closely with her commitment to its social implications.

“I don't like using the word ‘collector,’” she stresses. “I feel like I’m just a host for the work and it’s a privilege to have them for the time they’re with me. My curiosity lies in how art can be used to build stronger communities or as a vessel for social justice. I’m collecting ideas on how to work toward that.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

Big Shot

If an image of Jim Morrison, The Rolling Stones, Simon & Garfunkel, The Mamas and the Papas, The Beach Boys, or The Byrds has been burnished into your memory, chances are you’ve been touched by the work of Guy Webster

If an image of Jim Morrison, The Rolling Stones, Simon & Garfunkel, The Mamas and the Papas, The Beach Boys, or The Byrds has been burnished into your memory, chances are you’ve been touched by the work of Guy Webster

Written by Katherine Stewart | Photography by Guy Webster

Perhaps the most influential visual chronicler of the great age of classic rock, Guy Webster shot album covers for dozens of bands as well as portraits of prominent cultural figures including Dennis Hopper, Jane Fonda, Ravi Shankar, Jack Nicholson, Eva Gabor, Truman Capote, Judy Collins, Rock Hudson, Janis Joplin, Barbra Streisand, Mick Jagger, and presidents Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton.

During the Nixon administration, Webster decamped from California, where he was raised, to Italy and Spain, returning after a half dozen years. He met and married his wife Leone, and they moved to a restored farmhouse in Ojai, where they raised daughters Merry and Jessie, enjoying visits with Sarah, Michael, and Erin—Webster’s children from his first marriage. In 2019, at age 79, Webster died of a longstanding illness. We chatted with his daughter Merry to learn more about the man behind the legend.

How did your father manage to capture the iconic images he produced?

My father obtained a master’s degree in art history at the University of Florence and used his understanding of light and composition from classical paintings in his own photography.

A majority of the artists he photographed were living the high life of the ’60s and ’70s. Many were experimenting with drugs, and they often needed wrangling. At the time my father shot the iconic bathtub cover of The Mamas and the Papas album If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears, the band was hanging out in a house in Laurel Canyon. There was a large bowl of weed burning in the middle of the living room, and no one had the stamina to go outside to shoot the album cover. So my father told them to get in the bathtub and just had them relax there while he took the photos.

What are some things that few people know about your father?

My father was an epic storyteller. He would find a corner seat at a party and let people come to him. By the end of the night, you could always find him holding court to a large group enchanted by his

life stories.

His father, Paul Francis Webster, was an award-winning lyricist who won three Oscars and a Grammy and was nominated for 14 Academy Awards. So music was a big part of my father’s upbringing. He was influenced by everything from opera to early folk to 1970s rock and would test my sister and me on names of blues and opera singers during our daily carpool.

“He credited Bob Dylan with orienting his life toward social justice, and he loved the values the ’60s brought to society.”

What type of music did he enjoy listening to at home?

In his early teens, he had a serious injury to both his hands. To ease his boredom while recuperating, he began listening to opera on his radio—this began his lifelong love and study of the genre.

In his studio, in the car, and at home, he loved listening to the blues, opera, and classic folk music—and he often returned to Van Morrison, who was a favorite. He credited Bob Dylan with orienting his life toward social justice, and he loved the values the ’60s brought to society. He also regularly listened to the artists he worked with, since many of them were his close friends.

How did he relate to you and your sister as children?

My father wasn’t a traditional “father figure” in that he didn’t check up on our grades, enforce bedtime, or reprimand us. My mom, Leone, was the person who looked after us in those ways. He did teach us a lot about culture, history, music, and classic movies though. He wasn’t shy about regaling us with his irreverent adventures and subsequent life lessons.

He also volunteered to teach photography at our school (The Oak Grove School in Ojai) so we could learn about the darkroom and understand lighting and composition. He was instrumental in inspiring many of his students to pursue photography careers.

Tell us about his passion for motorcycling.

Many people also knew him as a world-renowned collector of antique Italian race bikes. He had close to 100 beautifully restored motorcycles in the barn in the backyard of our family home. He went on rides through New Zealand, Costa Rica, and Mexico; traversed the entire United States many times; and visited every single national park on his bike. His rider friends have always said how wonderful he was to ride with—so sure, steady, adept yet fast. He regularly hosted open houses where aficionados from all over the country came to see his collection. But he was not a typical collector; he was very Buddhist in his detachment to material things.

“My father was an epic storyteller. He would find a corner seat at a party and let people come to him. By the end of the night, you could always find him holding court to a large group enchanted by his life stories.”

Did your father have a daily routine?

My dad liked to go out to coffee every morning. It was a habit that began when he lived in Europe in the early ’70s and remained a large part of his routine until his final days. A loyal group of friends would join him every morning, and they would often invite others to join their table. It was a very eclectic group of people of all ages. They adored him, and often made him feel like the unofficial mayor of Ojai.

His photo studio in Venice was also a hub for friends and other artists. He was such a sociable person and cultivated friendships from so many of his interests. My sister Jessie (now a professional photographer) worked for him in his studio as an assistant for 14 years along with his other assistant, Lisa Gizarra.

Tell us a bit about your father’s later years.

His stroke changed his life dramatically, but he was able to keep working with aid from friends and his assistant Khaled Fouad, who would help set up his camera. Only a month before he passed away, he put on a show at the Porch Gallery in Ojai based on the metaphor of the safety masks worn during the Thomas Fire. He shot portraits of a multitude of Ojai locals with their own hand-made masks, metaphors for the safety masks but crafted in ways that reflected their unique personalities. The show was a huge success with over 250 people in attendance. •

See the story in our digital magazine

Band of Brothers

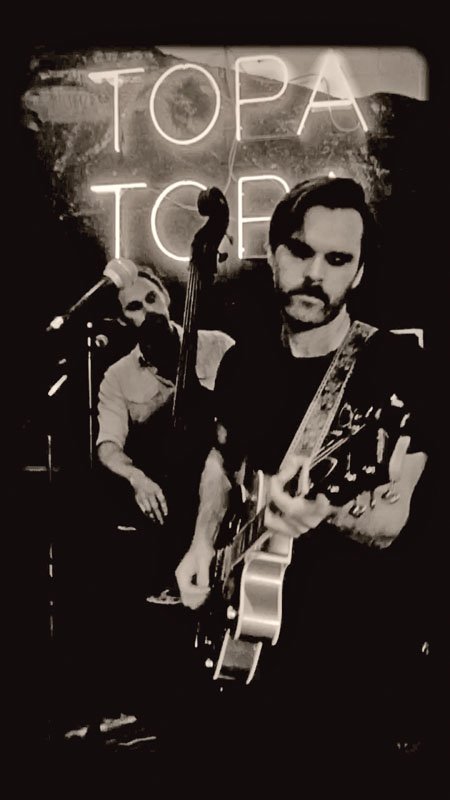

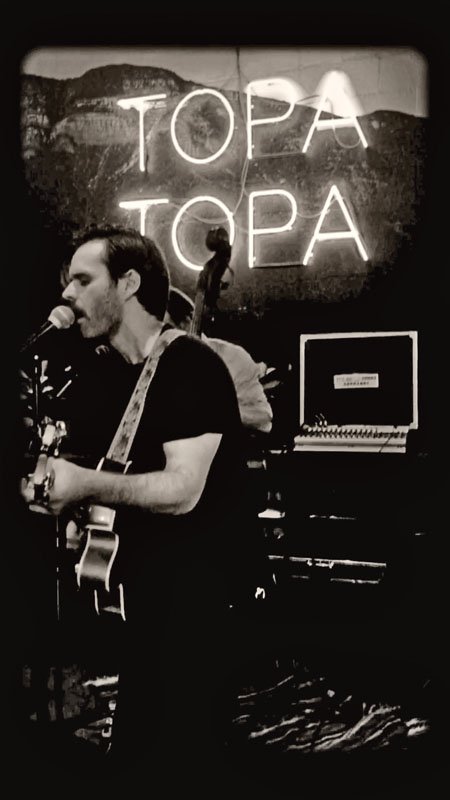

Getting down and dirty with the all-American trio The Brothers Gerhardt, who are bringing folk-country rock music to the Central Coast

Left to right: Nels Gerhardt on upright bass, Jacob Gerhardt on the fiddle, and Peter Gerhardt on vocals and guitar.

Getting down and dirty with the all-American trio The Brothers Gerhardt, who are bringing folk-country rock music to the Central Coast

Written by Claudia Pardo | Photographs by Courtney Ellzey

Influenced by music legends such as Willie Nelson, Merle Haggard, and John Prine, and the sounds of newcomer roots country singer Tyler Childers—along with sundry genres from indie/pop to rock and roll—The Brothers Gerhardt is establishing a growing popularity for themselves in Santa Barbara County.

This is most certainly because they are great musicians. Their music is hardy, with unhurried melodies, evocative of the craggy coastline and vastness of the area where they grew up. It’s also the result of being classically trained at an early age in music theory and composition—invaluable skills inculcated in them by countless hours of practice.

But there is something more—something special about them.

The Brothers Gerhardt have set off to ride across the wide expanses of Santa Barbara County, selectively playing gigs in local venues. For more information on upcoming shows, visit thebrothersgerhardt.com.

Jacob, Nels, and Peter Gerhardt epitomize brotherly love on and off stage. The singer/songwriting trio has a tight-knit relationship that many siblings aspire to have (and some may even envy). People love them. Their commitment to one another and their dedication to family tradition is inherent in their music. Their onstage performances for fans, friends, family, and new audiences transmit a candor that is impossible to ignore.

Born and raised in San Luis Obispo County, the Gerhardt boys grew up on a small farm, delighting in the freedom that their mother, Pam, and father, Jim—a private school teacher and a research engineer, respectively—granted them. Jacob recalls riding bikes on dirt roads, taking late-night walks to the river, photographing wildlife, playing with snakes, and engaging in all sorts of daring and exciting activities with his brothers. “The river behind our house was an extension of our backyard,” recalls Peter, a furniture builder and the principal song writer of the group. “We had the freedom to explore and use our imagination.”

“Whether we’re in the backcountry or on stage, it’s all based on the trust and support that we built growing up”

Television was a rare and special treat. Although they did get to watch the Olympics and movies from time to time, their limited exposure to television gave them the opportunity to spend their time outdoors, adventuring. They worked hard and played harder—outside. “We may have had more scrapes and bruises than kids today, but we turned out all right,” jokes Jacob.

Inspired by the Olympics motor bike racing they watched, the boys took on mountain road biking. The Central Coast proved to be idyllic for this diversion. Not surprisingly, recreation became an occupation for Jacob, who currently rides professionally as a cyclist for Clif Bar.

Growing up in the country also gave them permission to learn new skills. Their natural

knack for building things stemmed from their father’s side. Their great-grandfather was a furniture maker in Sweden and passed on the skill through generations. Jacob still uses the same welder that his grandfather used to build Indie 500 cars in the 1970s.

Nels has been married to Katherine Gerhardt, an avid surfer and bronze sculptor from San Diego for two years. Their toddler son, Nelson Ford, attends every one of dad’s shows. “Playing music is the framework that brings us together,” says Nels, “it’s the unspoken nuances on and off stage that keep us together.”

Peter’s wife, Jess, an environmental scientist from Santa Barbara, is also consistently supportive of the musicians. “Our relationship and this music would not be possible without this foundation,” says Peter. “Whether we’re in the backcountry or on stage, it’s all based on the trust and support that we built growing up.”

“Playing music is the framework that brings us together, and it’s the unspoken nuances on and off stage that keep us together.”

With an unassuming demeanor and rough-hewn good looks, The Brothers Gerhardt’s tunes pay tribute to tradition—a time when drinking from the garden hose, spitting scrapes clean, and cultivating good relationships at home were the norm. It’s Americana at its best, and it’s what makes them special.

See the story in our digital magazine

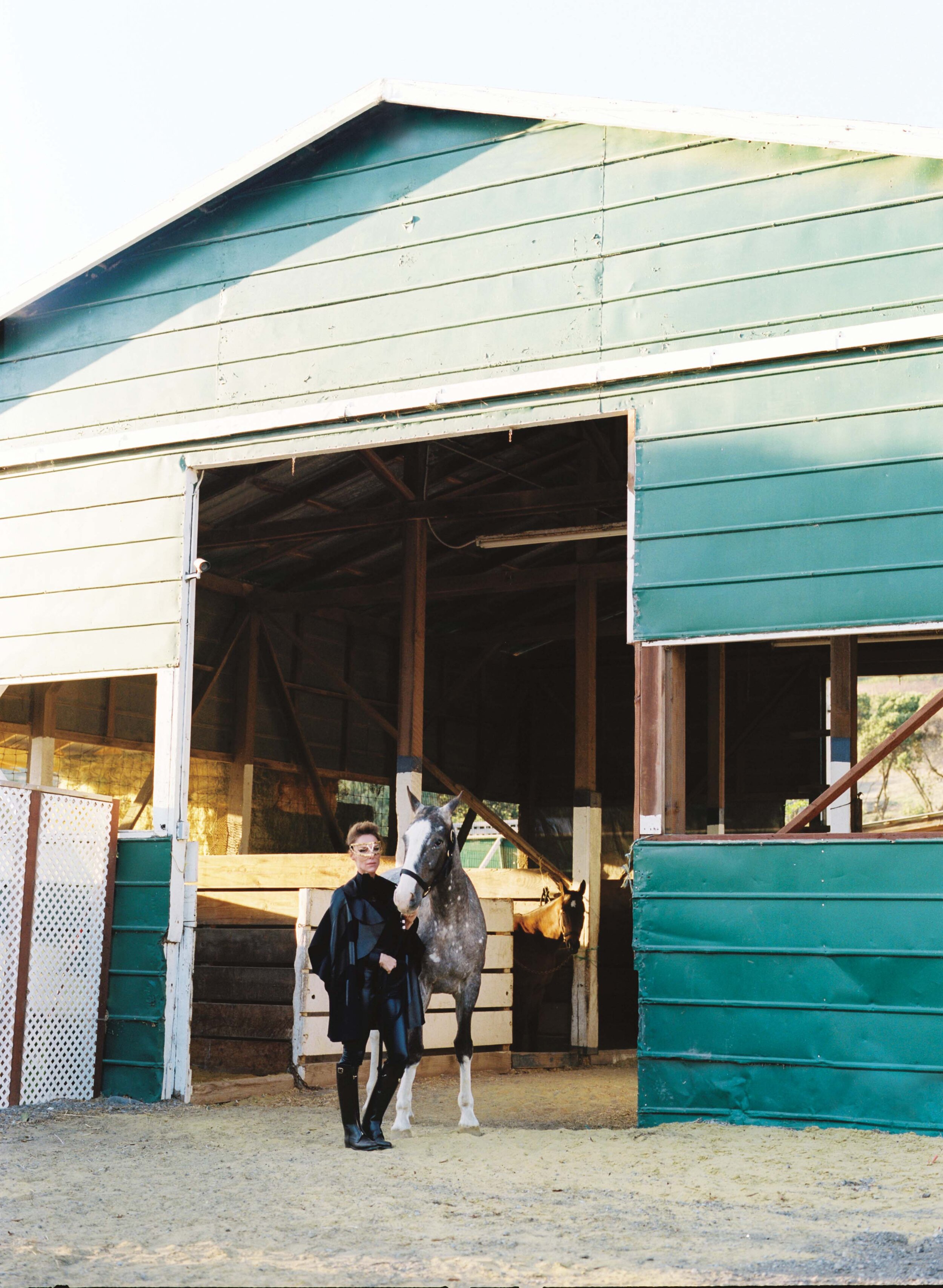

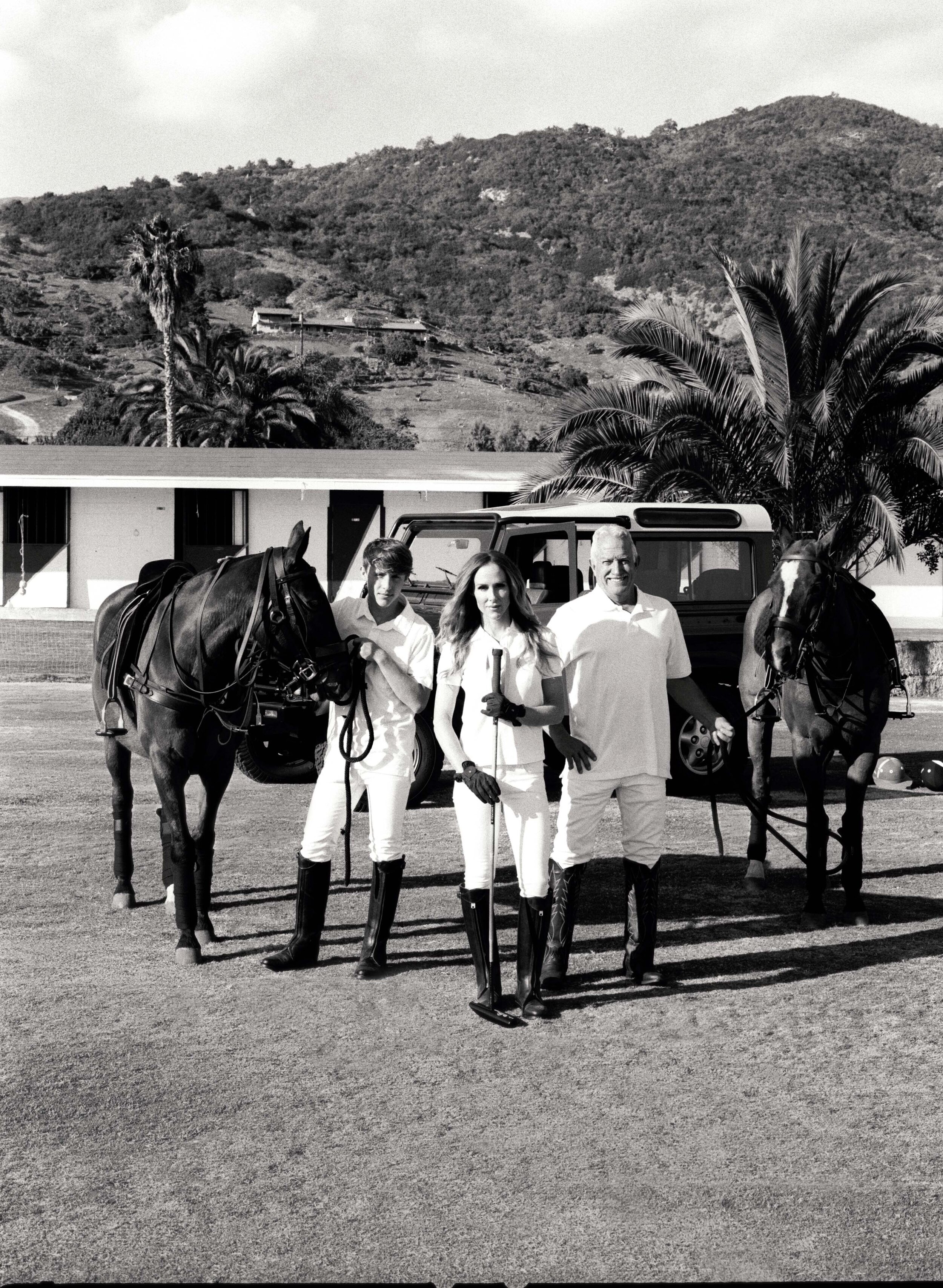

A Lucky Horseshoe

Memo and Meghan Gracida see polo in the future of the Santa Ynez Valley

Memo and Meghan Gracida see polo in the future of the Santa Ynez Valley

Written by Joan Tapper

Photographs by Dewey Nicks

You can’t miss the gleaming silver. Sit down to chat with Guillermo “Memo” Gracida and his wife, Meghan, in their Santa Ynez ranch house, and your eye inevitably turns to the shelves of shining trophies and statues that honor his achievements as a top world polo player. There’s a replica of the U.S. Polo Open cup, which Memo has won 16 times in his career. There’s the coveted fluted bowl from the Argentine Open, the Gold Cup of the Americas trophy, and the British Queen’s Cup, which Elizabeth II presented to Memo twice. The hardware is impressive, but what Memo really wants to talk about is why he and Meghan have now relocated to this area and his vision for the property they call La Herradura.

The word means “horseshoe,” he says, and it hearkens back to the name of the Mexican polo team Memo’s father fielded with his siblings. “They were the only set of four brothers to win the U.S. Open,” he says proudly. “That was in 1946. Father was a great mentor. He taught me to play and gave me a love of the sport.”

And that’s what Memo is now hoping to pass on to others at La Herradura by teaching and coaching both people and horses. “We came to the New World of the West Coast with energy to create a polo center. This place is a dream for a horse lover,” he says. “It’s the ultimate horse property.”

“La Herradura means “horseshoe,” and it hearkens back to the name of the Mexican polo team Memo’s father fielded with his siblings. “They were the only set of four brothers to win the U.S. Open,” Memo says proudly”

Memo has been coming to this part of California for the last 30 years, usually just for three or four weeks at a time as part of the professional circuit that moves from Palm Beach to England, Santa Barbara, Texas, New York, and Argentina. He happened to be here in September 2012, waiting out a hurricane in Florida, when he met Meghan, whose roots are in Santa Ynez and San Luis Obispo. When she began working in West Palm Beach a few months later, they reconnected and, after a whirlwind courtship, married almost five years ago. They bought the 45-acre ranch—a onetime Arabian horse farm—in December 2017.

The 3,800-square-foot house on the property, built in 1973, needed more than a little work. Walls were removed, the kitchen and master suite renovated, and the exterior totally redesigned, with other changes still to come. But the equestrian facilities—including barns, 60 stalls, fences, and paddocks—were all horse ready.

“We came to the New World of the West Coast with energy to create a polo center. This place is a dream for a horse lover. It’s the ultimate horse property.”

There are three large barns, including one with living quarters for half a dozen grooms, and 13 big pastures. “We have 100 horses, both ours and other people’s,” says Memo, “and our days are spent looking after them—working them, resting them, training them every day. We also run clinics and matches. It’s a three-ring circus!”

“People come for clinics and lessons from all over the world,” he continues. “There aren’t so many polo schools on the West Coast. My goal is to get new blood in the game and teach all different levels. We have ideal beginners’ horses—responsive and well-trained—and a safe environment with a staff dedicated to producing the best service.”

And the polo players—newbies and veterans alike—are learning from one of the best. Memo held a 10 handicap—the highest rating—consecutively for 21 years, and though he doesn’t play competitively as often now, he enjoys teaching others. That includes Meghan, who had never ridden before but now holds a 3 woman’s handicap and plays regularly on La Herradura’s women’s team. “She’s a great athlete,” Memo says. “She can ride any horse.”

“I get great satisfaction from seeing a person learn to make a great play,” he continues, “and seeing young horses and young players do something new.”

“When you’re on the field, you’re not thinking about anything else. The connection of horse and person is epic”

Until recently, weekend matches as well as riding lessons and stick-and-ball sessions have taken place at Piocho ranch, five minutes away. But as of September, there’s a new polo field at La Herradura. Creating the venue has been a huge project. “It was a horse pasture,” says Memo, “and to grow grass for a polo field, you have to do a lot of prep. We were lucky to get a lot of fill from the mudslides to even it out. Then we seeded it. You have to let the weeds grow out, then you can kill them. It’s taken a year and a half start to finish.”

The Gracidas hope to develop other fields in the future, with the goal of building a club with 150 members. Polo is “great for people who have been successful in life and are looking for a challenge,” says Memo. “But there haven’t been a lot of opportunities to learn, or a place nearby where people can try the game and see if they like it.” In fact, even though people may think of the Santa Ynez Valley as horse country, the number of animals has dwindled as ranch land has been converted to vineyards.

Meghan points out that for Memo, the important things are his family, horses, and polo, and indeed he’s a superb advocate for the sport. “When you’re on the field,” he says, “you’re not thinking about anything else. The connection of horse and person is epic.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

California Spirit + Southern Charm

Author Frances Schultz invites us into Rancho La Zaca where good food and a harmonious setting feed both the body and the soul

Author Frances Schultz invites us into Rancho La Zaca where good food and a harmonious setting feed both the body and the soul

Written by Sally Daye

The Southern Style of the title is epitomized by Frances herself and what she brings to her brand of hospitality, which she sees as a calling. “Hospitality—if we allow it, if we intend it—connects us to one another and to community.”

“How we do love our Santa Ynez Valley. Which, by the way, I did not know before coming to it. Somehow I’d missed this gorgeous enclave a stone’s throw from Santa Barbara. It was worth the wait.”

And so begins the latest book by lifestyle maven and transplanted insouciant Southerner Frances Schultz—California Cooking and Southern Style: 100 Classic Recipes, Inspired Menus, and Gorgeous Table Settings. How she got here from her native North Carolina is another story, but suffice to say, “Years ago on a road trip, my husband Tom [Dittmer] stopped by here and thought it was the prettiest ranch country he had ever seen. He knew then he wanted to have a ranch here one day, and here we are. And we love nothing better than sharing it with family and friends.” In fact she loves it so much she had to share it with the world. “Seemed like there was all this goodness and beauty here bustin’ to get out. I just wanted to help it along.”

Frances Schultz at her ranch; like many houses in California, Rancho La Zaca is all about outdoor living. “The porch at left is where we have dinner most nights,” she says, “the vine-covered porch at the right is our weekend lunchtime spot.”

Also “helping along” is Santa Ynez resident and chef Stephanie Valentine, who wrote and tested the book’s recipes. Trained at The Culinary Institute of America in New York and a star protégée of legendary Chicago restaurateur Charlie Trotter, Valentine also served as executive chef at Roxanne’s, a premier raw food restaurant in San Francisco. Says Frances in her book’s Cook Notes, “While I appreciate the many beneficial qualities of raw food-ism, Stephanie no longer subscribes. Nothing against raw food-ists, but thank goodness.” She continues, “The California Cooking in the title is as much about place as it is about food. Our Central Coast is blessed with a year-round growing season and some of the best farmers and winemakers in the country. We created recipes for what we love to eat ourselves. Our aim is not to be startlingly original, and the recipes aren’t complicated. Some do take time. It’s a labor of love. No one says it’s a ‘nothing-to-it’ of love. Isn’t the creating half the fun? This is tried, true, doable, and delicious home cooking of the kind that makes us feel warm and welcome, with a fresh California spirit and a spirited Southern charm. Like a good old friend we haven’t seen in a while, familiar but with new tales to tell.”

“Our Central Coast is blessed with a year-round growing season and some of the best farmers and winemakers in the country. We created recipes for what we love to eat ourselves.”

“Good food and a harmonious setting feed both the body and the soul,” she says. Fortunately, the setting was already there. “Occasionally I dress it up with flowers and such, but the backdrop of our Rancho La Zaca is inspiration in itself.”

Situated along the Foxen Canyon Wine Trail, Rancho La Zaca is part of an original Mexican land grant comprising vineyards, oak savannas, valleys, and mountains as far as the eye can see. The setting no doubt appealed as well to previous owner and actor James Garner, who built the current Hugh Newell Jacobsen-designed, contemporary-style house Schultz and Dittmer live in today. Writes Schultz, “Mr. Jacobsen was a favorite of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who had him design her house in Martha’s Vineyard. Funnily enough, the Garners bought the property from actor-director Herbert Ross, then married to Jackie’s sister, Lee Radziwill.” Today’s guests, admits Schultz, “are mostly unfamous but ever-cordial family, friends, and those who might become friends.” As long as they do not use their cell phones at the table, she adds. “I cannot believe there are people who still do that.”

With her Southern manners intact, spirited humor, stylish grace, and some 100 recipes and as many photos, Schultz’s book also marks the chapter following her popular The Bee Cottage Story: How I Made a Muddle of Things and Decorated My Way Back to Happiness. A memoir cum decorating chronicle set in The Hamptons, this poignant and funny tale ends in California with a question mark. The question for now seems well answered in California Cooking and Southern Style. With typical irreverence Schultz notes, “I should have made the new book’s subtitle How I Went from Down in the Dumps to One Dinner Party After Another.”

See the story in our digital magazine

In Elaine's Lane

Since moving to California six years ago, iconic model and mom of three Elaine Irwin has made Santa Barbara—now including the Rosewood Miramar Beach—one of her favorite getaways

Since moving to California six years ago, iconic model and mom of three Elaine Irwin has made Santa Barbara—now including the Rosewood Miramar Beach—one of her favorite getaways

Photography by Mark Champion | Styled by Alison Edmond | Written by Degen Pener

Elaine Irwin first visited Santa Barbara in the 1990s. This was back in the day, the superstar model recalls, “when we did these long photo shoots. I stayed here for about three weeks, and since then, I’ve always had a great place in my heart for Santa Barbara.” That was also in the era when models—as opposed to celebrities—still regularly graced the cover of Vogue magazine. In 1989 and 1990, Irwin garnered three solo covers, her first one shot by the legendary Irving Penn, proclaiming the then-19-year-old Pennsylvania-born beauty “All-American!” Within three years, the 5’11” model, who went on to become the face of Almay and Ralph Lauren, married singer John Mellencamp and moved to the heartland, living in Bloomington, Indiana, for more than a decade and a half.

Today, she’s a Californian through and through. “I’m the biggest fan of California,” says Irwin, who lives in Venice with her husband of seven years, media entrepreneur Jay Penske (owner of Variety, WWD, and Rolling Stone) and their 6-year-old daughter. “The quality of life is so good,” she says, adding, “I do not miss scraping ice from my windows—just to think of it makes me shudder.”

Among her favorite places to visit is Santa Barbara. “It’s such a beautiful town,” says Irwin, who recently celebrated Mother’s Day with her mother and her daughter at the Rosewood Miramar Beach. Her daughter loves exploring the children’s science discovery center MOXI, visiting the zoo, and walking on the pier. “Santa Barbara is just far enough away from Los Angeles that you feel you’ve really gotten away.”

Her local friend circle includes jewelry designer Sheryl Lowe, who recently shot Irwin for a fall ad for her collection. Why she chose her for her Santa Barbara-based line? “Elaine is the epitome of a timeless beauty in every way. She is a role-model mother, wife, and friend,” Lowe says. Her biggest focus is striking the right balance as a mother. Taking a break from social media since last December has helped immensely. “I have so much more time with my day. It’s very liberating,” says Irwin, who has two sons from her first marriage—25-year-old Hud Mellencamp lives in L.A. and works for a video technology company; 24-year-old Speck just graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design. Meanwhile, her daughter just graduated from kindergarten. “I had no idea how much fun it would be to have a girl,” says Irwin. “It’s good to have things that you do outside of your home, and it’s good to have a lot of investment in how you raise your kids. I’m really trying to spend time and enjoy my little one. I love that part of my life.” •

See the story in our digital magazine

Point Break

Landscape Designer Scott Shrader's Ode to Rincon and Outdoor Living

Landscape Designer Scott Shrader's Ode to Rincon and Outdoor Living

Photography by Lisa Romerein

Shrader's The Art of Outdoor Living (Rizzoli, 2019

Alexandra Vorbeck loves transforming properties as much as—maybe even more than—I do. She is always looking for another challenge. When she found this beach house property north of Los Angeles, she could not resist. The entire property was in very sad shape. The county had recently condemned the house—relocated from Carpinteria in the 1960s—which had been built on sand without any footings or foundations and added on to haphazardly over the years. The existing gardens included only one semi-functional outdoor space, a pagoda. A sunken pond occupied the actual sweet spot for commanding the view, a long vista to one of California’s great surf breaks. But the location—just a short walk from the beachfront, and next to a tidal lagoon—was perfection. Vorbeck imagined turning it into her own private Idaho of a retreat to share with family and friends: the ultimate, California-casual getaway, suited to a dress code of T-shirt, shorts, and flip-flops.

To be here is to want to interact with the water, air, and views, day and night, from all points on the property. To make that possible we used materials that bring the feeling of the shore right up to the threshold of the house and visually extend the experience of the living spaces to the beach and water beyond.

“Beyond the walls, we casually integrated environments conducive to lounging, casual dining, conversation, and just hanging out.”

In order to give direction to the large gestures and small details of our redesign, I developed a story of a tsunami landing on the house. When it passed, it left the house engulfed in an almost accidental landscape of randomly scattered boulders (in a practical touch, these serve as impromptu seating), drifts of sand, and an assemblage of boardwalks that tie the house and gardens together. Working with architect CJ Poane, we opened up the interior of the house with axial views, focal points, and moments that reflect the ocean, and we planked the walls and ceilings (picking up the boardwalk theme) to create easy, breezy, light-filled rooms visibly in synch with the surroundings. Beyond the walls, we casually integrated environments conducive to lounging, casual dining, conversation, and just hanging out—a fire pit, an easy area for four to six to share a meal, play cards, or shuck oysters; a larger lounge area for bigger groups, plus, of course, the numerous boulders that offer incidental places to sit or put down a drink.

Since we wanted a random effect, it did not make sense to plot every single plant and every single position obsessively. We knew the plant palette had to consist of drought-tolerant salt-lovers native to California. We knew we would create an arbor of fig trees off Vorbeck's master bedroom and find a worthy specimen—which turned out to be a strawberry guava—to commemorate the birth of her first granddaughter. I sketched in the boardwalks with a can of spray paint. We figured out the basic structure for the landscape. With four large trees—including a spectacular, mature Monterey cypress—still standing proud, we began to shape our vision with the understory, arranging Metrosideros to grow into a hand-clipped screen around the property’s perimeter. Interspersed are 15 additional Monterey cypress trees intended to add, eventually, impressive tall shafts of green.

While the house and garden were still in construction, Vorbeck held a “naming” party to select a moniker for the house. The unanimous favorite? The Sandbox. We have now guided The Sandbox through the process of becoming for more than five years. As it continues to mature over the next 30 or 40 years, my hope is that it will be demonstrated that we’ve planned well for its future—and that, with care, it will only continue to grow more and more into its best self.

See the story in our digital edition

Power of the Pony

Investing in polo horses is crucial to getting into the game

Investing in polo horses is crucial to getting into the game

Written by Megan Kozminski

Photographs by Courtney Ellzey

Some people jump in and purchase a string of half a dozen ponies straight away; others buy just one to start, testing out their new passion (and pocketbook). Shopping for that perfect first pony can be complicated. Polo horses have personalities, habits, strengths, and weaknesses, just like people. There’s also a lot to learn about the sport of polo, the horse industry, and even basic equine science.

Find people in the industry who you trust. Determine your budget and gather information from seasoned coaches, players, or professionals who can help you navigate.

Next comes the fun part: Ride as many polo ponies as possible. Try a pony at least twice—a stick and ball session, and if that goes well, a practice or game chukker. If you are trying dozens of horses, keep notes on the age, conformation, and under-saddle details for each, and always have a reputable veterinarian conduct a prepurchase equine health exam.

The most important advice to any polo shopper is buy the pony that makes you a better player based on your current skill and handicap. You want to feel like a million bucks every time you walk onto the field. Always keep in mind that after the purchase, it costs the same to feed a mediocre horse as it does to feed your perfect equine partner.

“This year, I realized the power of the pony. It took me four years to understand exactly what that means. For me, upgrading to the first-class breeding program of La Dolfina Valiente and purchasing the next-level string will give me the tools to take my game to the next level. This means compact, speedy, handy horses that stop and turn on a dime. When you’re really new to the game, you don’t realize how important that is. Then one day you do! Polo is 70 percent horse, 30 percent rider.”

See the story in our digital edition

Double Vision

Polo player, professional model, and Instagram It girl Zinta Braukis strikes a pose at Cancha de Estrellas

Polo player, professional model, and Instagram It girl Zinta Braukis

strikes a pose at Cancha de Estrellas

Photographs by Courtney Ellzey

Hair and Makeup by Tomiko Taft

WHO Zinta Braukis, often called “Z” by family and friends.

“There is a fantastic, relaxed pace to life in Santa Barbara—it’s a great balance to my career and the adrenaline rush of racing down the fields on a galloping horse.”

WHAT Working as a professional model by day with such brands as Ralph Lauren and Lucchese, Braukis—who has been playing polo since the age of 14—is at her happiest in the saddle with her horses in Los Angeles and Indio.

DOUBLE DUTY Dubbed the equine Instagram It girl, @zintapolo has more than 80,000 followers and is in demand for her lifestyle posts of horses and polo.

TRIPLE THREAT Athletic, adventurous, and adrenaline seeking, Z recently earned her helicopter pilot license.

PASSION PROJECT “As with people, each horse’s personality is unique. It is truly a special relationship that develops. I teach them to trust me and that mutual respect is possible. It is an immense joy to see them flourish as a result—both in their personality and as an athlete.”

WORDS TO PLAY BY “To paraphrase Alexander the Great (one of the first polo players in history), ‘The world is the ball, I am the mallet!’”

Throughout: Tops, Rocio G., rociog.com; boots, Lucchese, lucchese.com; hats, Vanner, vannerhats.com. Special thanks to Sarah Siegel-Magness and Joe Henderson of Cancha de Estrellas for use of horses and location.

See the story in our digital edition

A Glittering Prize

The Pope Polo Challenge Trophy is intertwined with an interesting family history

The Pope Polo Challenge Trophy is intertwined with an interesting family history

Written by Joan Tapper

Photographs by Shannon Jayne Photography, Coral Von Zumwalt

Doyenne Edith Taylor Pope in the early 1900s.

Santa Barbara’s 2024 polo season kicks off with the 12-goal Folded Hills Pope Challenge, and when the winners step onto the podium on May 12, they’ll be lifting the Pope Polo Challenge Trophy in triumph. It’s elaborately crafted of sterling silver, an impressive two-handled urn—more than three feet from the bottom of its wooden base to the tip of the finial that crowns its acanthus-wreathed cover. And though its yearlong home is a glass-fronted case at the clubhouse of the Santa Barbara Polo & Racquet Club, the cup’s beginnings go back to San Francisco, where it was commissioned by society doyenne Edith Taylor Pope—after that city’s devastating earthquake and fire—as part of her efforts to lure polo-playing friends west. Eventually it honored her son George A. Pope Jr., a noted California player in the 1930s.

We owe stories and lore about the trophy to Edith’s great-granddaughter, Hope Ranch resident Geraldine “Geri” Pope Bidwell, who relates that the trophy was created at Shreve & Company, San Francisco’s preeminent firm of silversmiths, which not only dates to the Gold Rush era but is still thriving today. Why so large a cup? Well, according to Geri’s father, “Nana”—his name for Edith—“never did anything half way.”

“The first Pope Challenge was decided on April 4, 1909, when Burlingame beat England 6 to 5, a result etched onto the silver cup.”

The first Pope Challenge was decided on April 4, 1909, when Burlingame beat England 6 to 5, a result etched onto the silver cup. At the time, George Jr. was not yet 8, but Geri is sure he was watching from the sidelines, thrilled by the pounding hooves and the action. George grew up watching polo, loving horses, and learning the sport. By the age of 17, she says, he was an 8-goal player, and his win as the number-one player for San Mateo on March 22, 1934, is also inscribed on the trophy.

George was evidently a well-known figure in San Francisco-area polo circles—renowned enough to serve as a guide to a writer exploring the scene in 1938 for a story in Country Life and the Sportsman. And he’s said to have played numerous matches with and against polo legends like Charles Howard, Bill Gilmore, Robert Driscoll, and Bob Skene. He kept a low profile, however, preferring to let his prowess show up on the field.

When World War II broke out, George served in the army; and after he returned, he refocused his equestrian pursuits on breeding racehorses—with great success. He was the owner of Decidedly, the gray that won the Kentucky Derby in 1962, setting a Churchill Downs track record for one and a quarter miles in the process. George died in 1979, and the trophy eventually moved permanently to Santa Barbara.

A love of horses continues to run in the family. George’s son, Peter Talbot Pope, played polo at Princeton, though he denigrates his horsemanship: “We were terrible,” he claims. Geri herself show-jumps and trail rides. “One of the best things about riding a horse,” she says, “is that it puts us fully in the moment. Horses can give us power, wings, and a connection that feels timeless.” The only recent polo player has been her daughter Lucy, who competed in the Artie Cameron Memorial Polo Tournament for Juniors at the Santa Barbara polo club a few years ago.

“May the winners of the Pope Polo Challenge Trophy be the riders who have worked the hardest to know their horses, to honor and care for those horses well, to love this sport for the wings it gives them and the grace of God that blessed them with their horse.”

The family restored the trophy, and it shines more brightly than ever. The name of 2018’s tournament winner—Klentner Ranch—is on the cup. The next to hold that honor is still to be determined. But Geri’s wishes extend to all the teams who will take the field: “May the winners of the Pope Polo Challenge Trophy be the riders who have worked the hardest to know their horses, to honor and care for those horses well, to love this sport for the wings it gives them and the grace of God that blessed them with their horse.”

See the story in our digital edition

Out Of The Weeds

After legalization, Santa Barbara is poised to become the epicenter of cannabis farming

After legalization, Santa Barbara is poised to become the epicenter of cannabis farming

Written by Maxwell Williams | Photographs by Brian Bins, Curtis Peterson, York Shackleton

Up in Los Alamos, surrounded by greenery and lush farmland in every direction, York Shackleton kicks at a pile of horse dung. He looks and talks like any young farmer, wiry and rugged and proud of his crops. Except there aren’t any crops yet, not until the cannabis growing season begins in June. Still, mature plants in planters are lined up in a row on the seat of a picnic table by the farmhouse. “I have a lot of rare genetics that only I possess,” says Shackleton, as excited by plant propagation as any grad-school horticulturist. “We’re going to cut those down now and clone them.”

“Most of the farms are geared toward high-yield production, with an eventual eye toward the sort of cannatourism that will turn the Central Coast from wine country to weed country.”

Shackleton’s High Star Farms is one of an estimated 100-plus cannabis farms operating legally under more than 1,000 licenses in Santa Barbara County. It’s the most by county in the state, recently passing longtime cannabis stronghold Humboldt County, since the state shifted from medical to recreational cannabis at the beginning of the year. Most of the farms are geared toward high-yield production, with an eventual eye toward the sort of cannatourism that will turn the Central Coast from wine country to weed country.

All of the other farms are working under temporary permits, Shackleton says, but because he had been running large-scale grows in Monterey for years before buying the Los Alamos property—which features a hotel he plans to get online as soon as he can, and enough fields to grow thousands of pounds of cannabis—he didn’t qualify for the grandfathered temporary permit.

And because he was compelled to apply as soon as he could, he says that High Star has felt an urgency to pass through all the notoriously difficult, but necessary, hoops to get a business license, and they stand to be the first such farm in Santa Barbara County with one. No easy task, says the farmer/filmmaker (he’s directed movies starring Nicolas Cage and Guy Pearce) from Calabasas, who employed his mother to do the permitting. “They chose us as a guinea pig,” Shackleton says. “It’s a huge milestone. We’re in an area that’s premier land. It’s wine country. It’s very prestigious.”

Just a few miles down the 101 in the farmland outside of Buellton, Sara Rotman is also on prime land. A goat chews at her boot through a fence as she gestures to the area where her polo grounds were supposed to be. She’s an equestrienne, having played top-level polo for years, and her savvy is readily apparent, coming from the world of high-end fashion branding, where her clients were the likes of Michael Kors and Goop.

“Most of the farms are geared toward high-yield production, with an eventual eye toward the sort of cannatourism that will turn the Central Coast from wine country to weed country.”

But in 2014, after she closed on the property in Buellton, a life-or-death fight against Crohn’s disease debilitated her. Doctors put her on high doses of morphine, prednisone, and Remicade, a strong immunosuppressive that left her susceptible to, and nearly dead from, tetanus. After doing some research, her husband, Nate Ryan, convinced Rotman—who describes herself as a caffeinated, type-A personality—to try CBD, the nonpsychoactive version of cannabis. “Lo and behold, it worked,” she says with a laugh. “It was better for my pain, and it worked on my inflammation.”

Soon, the couple rejiggered the plans for the farm. And as with all Rotman endeavors, the plans turned into a full-fledged business. They produce a crop of organic outdoor-grown cannabis flower for other manufacturers like Select, a fast-growing company specializing in CBD vaping products. Rotman says she is looking to expand her own brands, Bluebird805 and the newly launched Busy Bee’s Farm Flavors, which focuses on vaping products with farm flavors like rosemary, honey, and pomegranate.

Rotman feels that the explosion of farming in Santa Barbara boils down to the growing conditions—the cool breeze and the fertile soil—which have long made the region a prime spot for Pinot Noir grapes and other produce. Still, Rotman says there are myriad challenges to running a successful cannabis business, not the least of which is pushback from already established farmers in the area, who believe the smell of cannabis will impact their wine, a concern that remains unproven.