Riviera Summers

A father and son capture the Luxe Life

A father and son capture the Luxe Life

Written by Lorie Dewhirst Porter | Photographs by Nik Wheeler and Kerry Wheeler

Santa Barbara’s resemblance to the European Riviera can’t be denied, because the visuals are so strikingly similar: ocean, beach, dramatic coastline, and beautiful people—which is why travel guides have dubbed the region the "American Riviera.” And like its European counterpart, our Riviera (and the lifestyle it embodies) is as much a state of mind as a geographic location, a duality of perception and reality.

From the 1950s onward, the public’s perception of the Riviera lifestyle was largely the creation of one man: American photographer Slim Aarons. His Technicolor images of the international café set living la dolce vita were splashed across glossy magazines like Town & Country and Life. His ability to access high society was key to his success; “I knew everyone” he told an interviewer several years before his death in 2006.Today, father-and-son photographers Nik and Kerry Wheeler offer a contemporary take on the Riviera lifestyle with The Wheeler Collective, an online platform for purchasing the duo’s custom-framed photographic images for the home. And there’s plenty to choose from: Their archive contains more than one million images from the 1960s onward, with subjects ranging from scenes of European leisure to celebrity pictures and photos of lost worlds. (A percentage of every sale goes to the World Land Trust.)

Like Aarons—who covered World War II as an army photographer—British-born Nik Wheeler began his career as a combat photographer. Initially based in Vietnam, he later covered conflicts in the Middle East for Newsweek and Time Magazine and eventually pivoted to travel photography. In 1999 he moved to Santa Barbara; since then, he has visited more than a hundred countries on assignment for National Geographic, Travel and Leisure, Islands, and others. He also produced several coffee-table travel books over the course of his career.

Nik’s son Kerry grew up in Santa Barbara. After attending USC, where he majored in global communication with a film minor, he spent several years in the entertainment industry. During a much-needed break, he traveled to Europe, taking photographs and posting them on Instagram, where the comments likened Kerry’s images to iconic images by—no surprise—Slim Aarons.

Given his upbringing, Kerry basically trained in photography from the time he could walk. The Wheeler family spent summers in Europe, based in a small village in the Languedoc region of France, where Nik had purchased a home in the 1970s. The family would take long road trips in an old BMW (affectionately known as the “red bomb”) for Nik’s travel-magazine assignments, and Kerry remembers his irritation with his father’s camera bag that “always had to be in the middle of the console by the stick shift, and it was so annoying because we were constantly stopping so he could get a shot.” (In true father-like-son form, Kerry continued the tradition with his own camera bag on his last European jaunt.)

But Kerry fondly recalls the exciting social environment the family enjoyed during those summer sojourns. Thanks to his father’s career renown, and the fame surrounding his glamorous mother, Pamela Bellwood (whose acting credits include a regular role in the wildly popular 1980s television series Dynasty), Kerry notes, “We were constantly engaging with very interesting people,” a group that included aristocrats, artists, writers, and journalists. In short, a world similar to what Slim Aarons documented decades earlier.

Santa Barbara’s resemblance to the European Riviera can’t be denied, because the visuals are so strikingly similar: ocean, beach, dramatic coastline, and beautiful people—which is why travel guides have dubbed the region the "American Riviera.”

Hammonds From Above, 2022, Santa Barbara, by Kerry Wheeler.

The Wheeler Collective emerged from a confluence of two disasters. The Wheelers’ Montecito home was inundated with mud from the 2018 debris flow, and Nik’s studio, containing 50 filing cabinets of slides—nearly the entirety of his oeuvre—was the first room to be hit. Kerry visited the site shortly after the disaster and vividly remembers having to inform his father that the file cabinets were likely destroyed. “It was pretty devastating,” Kerry recalls. “At the time we thought everything had been lost.” Fortunately, further inspection revealed the mud had been too thick to penetrate the filing cabinets, leaving the slides intact.

Two years later, when COVID took over the world, Kerry moved back home to Santa Barbara. Locked down and with time on their hands, Nik and Kerry began sorting through the trove of rescued slides, with Nik assuming he’d “digitize the good ones and throw the rest out.” But Kerry was intrigued by a batch of Nik’s lifestyle images. “I showed him a couple of his photos from Cannes,” Kerry says, and his father replied, “Why would anybody want a picture of an umbrella or somebody lounging on a lounge chair?”

They would soon find out. Kerry was contacted by an art collective seeking an iconic beach scene for a client, who selected one of Nik’s images (blown up to 9 by 13 feet) for the lobby of Florida’s Four Seasons Hotel and Residences Fort Lauderdale. And voilà, The Wheeler Collective was born.

See the story in our digital edition

King of the Coast

Artist STANLEY BOYDSTON captures the waves at Rincon through canvas, surf, and athletic tape

Artist STANLEY BOYDSTON captures the waves at Rincon through canvas, surf, and athletic tape

Written by Lorie Dewhirst Porter | Photographs by Sara Prince

Artist Stanley Boydston’s obsession with Rincon Point is as intense as any seasoned surfer’s. For several years, he has produced work based on the famous sets of parallel waves generated by the “Queen of the Coast,” a location coveted by surfers worldwide. But not everyone who views his paintings actually sees waves depicted in them. “When I say they’re wave sets at Rincon, [patrons] look at me like I’m speaking Greek,” says Elizabeth Gordon, whose eponymous gallery on Gutierrez Street in downtown Santa Barbara represents Boydston’s work, along with Chase Edwards Contemporary gallery in Bridgehampton and Palm Beach. “But that’s the neat point,” Gordon adds. “People’s impressions are all across the board.” In reality, the artist’s vibrantly hued canvases verge on abstraction, but upon careful examination telltale details—a horizon line, the frothy seafoam—emerge. Which is exactly how Boydston approaches his favorite subject: “I’m looking at the light, and I’m looking at the horizon, and I’m looking at the color relationship between the sky and the horizon. As abstract as these paintings get, I’ve seen that.”

Boydston’s color scheme comes straight out of the sixties. His penchant for pairing bright orange with dazzling pink stems from a childhood trip on Braniff Airways and his memory of female flight attendants clad in Italian designer Emilio Pucci’s avant-garde uniforms in eye-popping colors. Another influence was pop artist Peter Max, who specialized in psychedelic imagery painted in Day-Glo colors. “For me those colors were associated with something forbidden, because there were drugs involved and sexual awakenings involved,” the artist says. “I think that lingers in my art, the feeling that you’re doing something exciting.”

“When I say they’re wave sets at Rincon, [patrons] look at me like I’m speaking Greek”

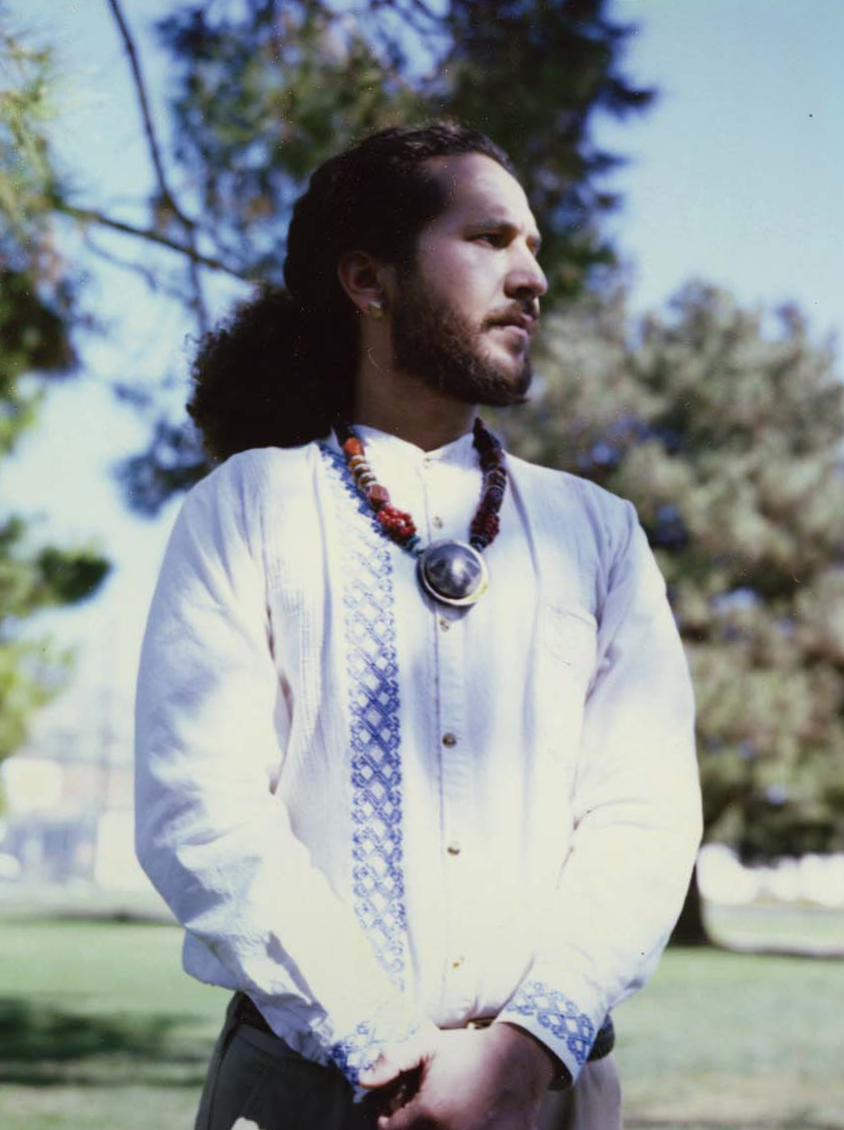

An Oklahoma native and a member of the Cherokee Nation, Boydston, 62, followed a circuitous path to Santa Barbara that included a childhood in Dallas, a decade in Spain, and a year in New York. He was a self-proclaimed “juvenile delinquent,” but his grandmother gently directed him toward painting, which he studied at the University of Texas at Austin, only to drop out after reading artist Salvador Dalí’s book 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship. “With those 50 secrets, I was more inspired than by what I was learning at Texas,” Boydston says. His parents, concerned by this turn of events, offered European travel and study as an alternative. He happily complied, and ended up living in Spain from 1980 to 1990, primarily in Madrid.

The years in Spain were productive. Fluent in Spanish—thanks to a beloved childhood family housekeeper from Acapulco—Boydston was in his element. “I made a point to learn as much as I could,” he says, “I started reading a lot and really got into French philosophy and German existentialism.” At the time Spain was still emerging from dictator Francisco Franco’s brutal regime, “and everyone was just blossoming.” Boydston became a regular at Madrid art openings, particularly exhibitions by Americans such as Robert Rauschenberg and Keith Haring, both of whom he met while there. He also began exhibiting his art there, primarily collages culled from newspapers, magazines, and street posters. An exhibition of Giuseppe Panza’s collection of conceptual art inspired Boydston in another direction, so he headed to New York for a year and focused on conceptual art and performance.

A romance with an opera singer led Boydston in 1993 to Santa Barbara, where he began painting landscape. The love affair ultimately failed, but Boydston discovered his cherished Rincon. At some point, he eliminated the curves from his compositions and began working exclusively with straight lines, using athletic tape for the waves. The tape reminds him of his father, who was a football player. (His mother was a beauty queen.) “Whenever I can use the athletic tape, there’s a joy in it,” he says.

In 2019, ten of Boydston’s Rincon-based works, entitled Creation/Emergence, were exhibited at the inaugural Biennale of Contemporary Sacred Art in Menton, France. This led to a special invitation to exhibit one of his paintings during the Venice Biennale. “It was just amazing,” he recalls, noting that the Venice experience was heightened by the discovery that his wife, Alicia Elizabeth, was pregnant with their son, Evan Star. (Boydston is also stepfather to daughters Violet Eve, 8, and Ava Love, 10.)

The quirky locale suits the artist, who says, "I just knew it was something special."

Given Boydston’s life experiences, it’s perhaps unsurprising that he managed to rent an outbuilding of a rambling old Montecito mansion for his art studio. The Palladian-style building with its majestic columns was evidently used as a “green room” for musicians who gave performances for the mansion’s owner. The quirky locale suits the artist, who says, “I just knew it was something special.” And the residence’s grand wood-paneled ballroom is a perfect venue for displaying his paintings.

Boydston continues to work on his wave paintings. “They’ll start out with a band of color,” he says, “and usually it’s orange. And then I’m basically weaving in and looking for my Rincon, within that.”

See the story in our digital edition

Off the Grid

NIKKI REED on living the simultaneous life of an eco-entrepreneur and country girl

NIKKI REED on living the simultaneous life of an eco-entrepreneur and country girl

Written by Kelsey McKinnon | Photography by Sami Drasin

On a recent morning, after Nikki Reed tended to the 15-plus farm animals that roam her biodynamic property, she and her 4-year-old daughter, Bodhi, trailered two horses over to a friend’s plot of land where the family, including Reed’s husband, actor Ian Somerhalder, were planning to camp for the weekend. It might not sound like it, but Reed was actually taking the day off from work, running her sustainable jewelry brand, BaYou with Love. “I live two lives, the life of a businesswoman and the life of a farm girl—on top of being a mom,” says Reed, 34, who still looks like she could play the lead in a Western.

By the time Reed was in her midtwenties, she had already achieved the Hollywood success many hope for in a lifetime. Reed broke onto the scene with the 2003 film Thirteen, a Euphoria-like account of her childhood in Culver City. Then in 2008 she landed the role of Rosalie Hale in The Twilight Saga, which catapulted her into tween stardom. She worked for a few more years before focusing on a simpler life in the Santa Barbara countryside. “To be fully transparent about it, I really did not want to be in the public eye anymore,” she says.

“I live two lives, the life of a businesswoman and the life of a farm girl—on top of being a mom”

Since she was a little girl, Reed has been an animal lover, bringing home rescue kittens and spending time at her grandmother’s farm in northern Malibu. She found her kindred spirit in Somerhalder (Lost, The Vampire Diaries, V Wars), and the pair married in 2015. “He and I together actually have always been a little bit dangerous when it comes to the animal situation. I remember when we were first dating, I called him, and I was, like, ‘So there’s this cat,’ and he's, like, ‘Say no more. Bring him home.’ And I was like, ‘Uh oh, this is gonna be really bad,’” she says laughing.

The pair’s move to the countryside has allowed Reed to flourish. In addition to BaYou with Love, she is the creative director of Løci footwear (a vegan sneaker line), a strategic advisor for the clean medicine company Genexa, and an ambassador for Leica Camera. “California has the ability to offer seclusion, but you can also be in driving distance to these major cities at the drop of a hat,” she says.

“Her goal is to connect with nature and show their daughter the beauty of the world, so that she too will see the value in protecting it. Reed says, “I think nature is the key to happiness. Really. I do.”

“I love the notion of being regenerative and not just sustainable. If you're not constantly seeking out how to do better, then you're not winning,” says Reed.

In many ways, Reed thinks of BaYou with Love as her first child. “The first place Ian took me was to the Louisiana Bayou, where he grew up. I just always thought that that was such a beautiful name. And I thought if I ever have a child I would [choose that] name,” says Reed, who launched her company two months before her daughter was born. For its jewelry, the company uses solar-generated diamonds from California and recycled gold, including metal recovered from discarded computers through a partnership with Dell.

Reed takes all the photography on the BaYou website with her Leica, which she brings with her everywhere. Her art prints (which are available on the BaYou site) feature dramatic landscapes printed on tree-free, cotton-fiber paper and offer a glimpse into her profound connection with the natural world.

“Reed’s dramatic landscape photography (printed on tree-free, cotton-fiber paper, no less) offers a glimpse into her profound connection with the natural world.”

“If I could like tell you my dream, it would be to achieve total food autonomy, to have zero connection to a supermarket, to city water, to anything like that—to be able to live without relying on any system. So, you know, we're not too far off from that,” she says. Reed’s sustainability practice includes rain barrels to catch excess water (she also drinks water from her own well when she can), hydroponic veggie gardens, and composting. For her daughter’s birthday, she suggests hand-me-downs as gifts, she hasn’t had a car in two years (she’s waiting for the Cadillac electric SUV), and she recycles clothing. If Reed has one indulgence, it would surely be the luxury Fleetwood RV that the family loves to travel in. (“When we go off grid, we are off the grid.”) Her goal is to connect with nature and show their daughter the beauty of the world, so that she too will see the value in protecting it. Reed says, “I think nature is the key to happiness. Really. I do.” ●

See the story in our digital edition

On the Waterfront

The Santa Barbara Yacht Club turns 150

The Santa Barbara Yacht Club turns 150

Written by Joan Tapper | Photography by Michael Haber

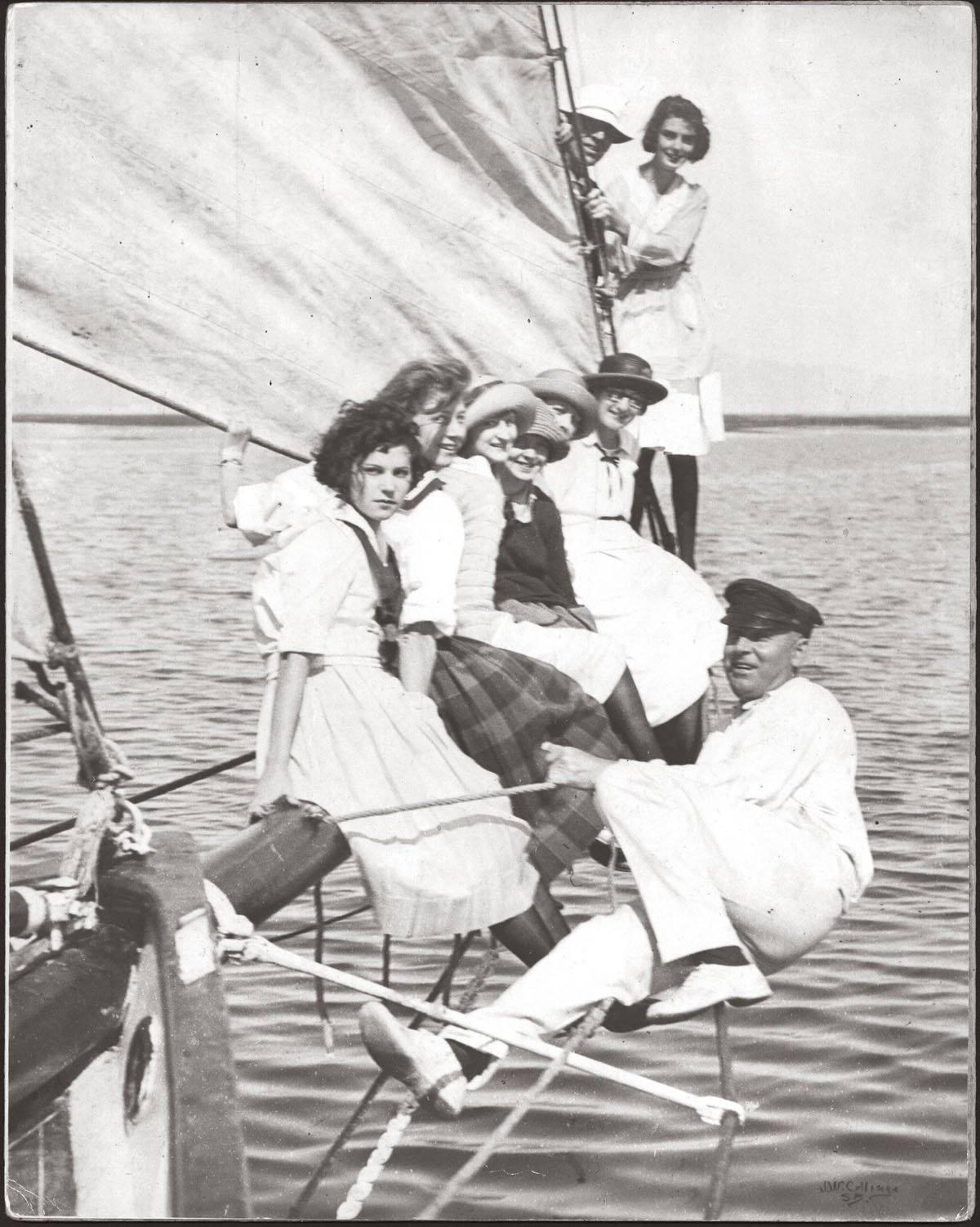

Archival imagery courtesy of Santa Barbara Yacht Club

There’s a lot to celebrate this summer at the Santa Barbara Yacht Club—150 years of history, to be exact. It was in 1872 that Lloyd’s Register of American Yachts, the repository of maritime records, noted the establishment of SBYC, making it the second oldest yacht club on the West Coast. That milestone is not to be taken lightly. And for those of us who associate the yacht club mostly with those picturesque sailboat races on Wet Wednesdays, it’s an opportune time to look at the bigger, splashier picture.

For one thing, it’s useful to remember that the yacht club is not just the on-the-sands building, which dates to 1966. No, the SBYC is and has always been, in the words of the current commodore, Eli Parker, “a great group of people who share a common interest in being out on the water.” And those interests have long been intertwined with the history of Santa Barbara.

Think back to the year 1872. At that point the town and its 3,000 or so residents were just beginning to be connected to the wider world. The railroad had not yet arrived. But that year the construction of John Stearns’s 1,600-foot-wharf meant that travelers arriving by sea no longer had to transfer to a small boat and then be carried unceremoniously through the surf to the beach. Tourism was on the horizon as wealthy visitors—including many boating enthusiasts from the East Coast—began to visit and stay. Members of the fledgling yacht club, who seem to have gathered in private homes at first, paid an initiation fee of $20 and annual dues of $10. Undoubtedly, they sailed for pleasure and raced for fun, taking good advantage of the wonderful climate and predictable afternoon breezes on the ocean.

The first regatta, a three-part racing event, was held here in 1907, and Milo Potter, a sailing enthusiast whose impressive hotel graced the waterfront, donated an elegant cup for the winner. The Potter Trophy, which is still awarded on Wet Wednesdays, is just one of the gleaming goodies that fill the pristine glass shelves of the yacht club building, which has undergone a top-to-bottom renovation just in time for anniversary festivities.

Other notable trophies are here as well, including the ornate Sir Thomas Lipton Cup, donated in 1923 by the Lipton Tea owner (and five-time America’s Cup contender) himself. That towering trophy of pure silver boasts shields, a yachting scene, a dolphin, a mermaid, Sir Lipton’s shamrock flag, and the yacht club burgee—its signature pennant. Also in the trophy case is a cup given by Italian premier Benito Mussolini in 1931. Stored in a closet during World War II, it was permanently retired and is now on display as an intriguing part of SBYC history. Not all the awards are serious though; the Royal Dolt-On trophy (a chamber pot) goes to the skipper with the biggest “goof of the year.”

The year 1923 also saw SBYC’s first clubhouse, a 20-foot-by-35-foot cottage at the end of Stearns Wharf that was destroyed in a storm just one year later. That was yet another reminder of the need to protect boats in a permanent harbor in Santa Barbara, which was the impetus for a decades-long campaign by club members to erect a breakwater here. They had organized a survey in 1921 to determine if and where they would construct a yacht harbor, and a year later the commodore, Earle Ovington, successfully lobbied town leaders by hosting a barbecue for about 300 on Santa Cruz Island. Major Max Fleischmann, the yeast company scion and a local philanthropist, wrote a check for $200,000 to the city, and by 1928 the initial breakwater was complete. Fleischmann and others, who purchased the wharf in 1927, commissioned famed architect Winsor Soule to build a clubhouse for the yacht club in 1929.

The years that followed were anything by smooth sailing, however. The Great Depression ravaged the club’s finances, leading to bankruptcy, and there were rifts among the members. Then with the onset of World War II, Stearns Wharf came under the control of the U.S. Coast Guard, and the harbor was closed to pleasure boats until September 1945.

By 1946 the yacht club had another building for its home, one of several that it would occupy for the next two decades. Even more important, wartime technology and the development of fiberglass meant that suddenly boating was no longer just a rich man’s sport.

Today the SBYC membership has grown to include families who enjoy racing—including women skippers and crew—and embrace water-oriented and social activities. The club holds about 200 races each year, among them the Wednesday evening and weekend races, as well as events that draw other competitors beside local sailors. Since 2005, the annual Charity Regatta in September has raised more than $2 million for Visiting Nurse and Hospice Care of Santa Barbara.

Also important are the youth activities that the yacht club has supported, from Sea Scouts and Mariners to the Santa Barbara Youth Sailing Foundation, founded in 1968, which encourages youngsters to learn to sail, build self-reliance, foster teamwork, and gain water-safety skills, and offers scholarships to local children for after-school and summer sailing programs.

“This is a club of volunteers that are totally engaged,” says Dennis Friederich, who served as commodore in 2004 and is chairman of the club’s milestone anniversary committee. “We’ve been valuable and contributing members of the community for 150 years.”

Of course, there have been memorable parties over the years, too. Trish Davis, a longtime member, remembers events honoring commodores that turned the dining room into a Greek wedding and another that transformed the place into an Italian restaurant, complete with singing waiters. “One big party is the luau in September,” she says. “The club is so old with such great traditions. There’s a diverse group of people, and we try to be welcoming. Something about being on and near the water sets us aside.”

This year, to celebrate the anniversary, the season kicked off at the beginning of April with a blessing of the fleet and the dedication of a commemorative plaque. There are three special races (the third of which is scheduled for August 3) with a 150th anniversary trophy to be awarded, and a video history of the club is slated to be finished by summer. Watch for a tall ship event as well, thanks to club members Roger and Sarah Crisman, who acquired a schooner—to be renamed the Mystic Cruzar— and have brought it to the Central Coast, where it will be used for scientific, history, and educational programs.

“To be part of the folks guiding the yacht club this year is an honor,” says Parker. “I’m thrilled that we were able to muster the resources and collective will to get the remodel done. It will serve us well for the next 30 or 40 years. It’s where we go to socialize and hang out. And it’s been great to see new, younger members. That’s our future.” •

See the story in our digital edition

Spirit House

Xorin Balbes embraces the philanthropic legacy of his new home

Xorin Balbes embraces the philanthropic legacy of his new home

Written by L.D. Porter | Photographs by Michael Clifford

Even in the midst of the current real estate frenzy, as properties seemingly change hands daily, certain grand Montecito homes will forever bear the imprint of their former owners. That reality is not lost on Xorin Balbes, whose newly renovated home is the former residence of beloved local philanthropist Lady Leslie Ridley-Tree. In fact, Balbes fondly recalls attending holiday parties where the glamorous nonagenarian—formally dressed, bejeweled, and in high heels—would stand at the home’s entrance for hours, personally greeting each of her guests, chosen from a wide swath of the community. (When asked about her famous soirées, Ridley-Tree says, “One person said to me, you know, it's quite shocking and surprising when I come to your house. I don't know if I'm going to meet the newspaper boy or the Queen.”)

The house itself was built in 1921, and the architect, Arthur B. Benton, was responsible for creating Montecito’s All Saints by the Sea church and also took part in designing the historic Mission Inn in Riverside. The home’s classical Mediterranean lines reflect the era’s enthusiastic adoption of European design details, including the use of arches and symmetry. Ridley-Tree’s husband, Paul, “fell in love with the house” and purchased it in the 1980s. In 2020, after having lived there for 35 years, Ridley-Tree gifted the residence to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, a longtime recipient of her largesse. Balbes, who admired the house for years, happily acquired it from the museum.

Known for renovating and restoring significant properties with his firm, Xorin Homes, Balbes is a seasoned real estate developer and designer. For the past four years, he’s focused his energy and talent on renovating exclusive Montecito properties. Which explains why his modifications to the former Ridley-Tree residence, achieved with his design partner, A.J. Bernard, took a mere 15 months. Balbes calls it his “forever” house, a sign he’s ready to settle down. Another sign is his recent marriage to floral curator Truman Davies, which recently took place in Tulum, Mexico—not to mention the addition of two adorable doodle dogs, Yoshi and Kenzo.

Respecting the original design, Balbes did not alter the footprint of the house and limited major changes to interiors. The dark wood paneling was repainted white throughout, with the exception of the spectacular dining room, whose walls are a rich gray-blue hue. The kitchen was expanded into a sleek minimalist Bulthaup masterpiece. Upstairs, the loggia’s ceiling was raised and vaulted, mirroring the trio of arches on the building’s exterior. The basement was transformed into a spacious yoga studio, with views to the garden.

Over the years, Balbes has developed his own approach to interior design, which involves layering distinctive objects and furniture from different eras. “I like bringing different things together, but it’s not easy,” he says. “I always thought, what if you walked into a space that’s timeless, where you can’t identify the time period it was done. There’s a comfort to the soul in timelessness.” To achieve that balance, he sourced the majority of the home’s contents, including art, from online auction houses around the world.

The glass-enclosed conservatory with its checkerboard tile floor—one of Balbes’s favorite rooms—has a circular wood-and-chrome bar with matching leather-topped stools he discovered in Paris, a Murano glass chandelier, and a 1960s bronze metal chess set by Pierre Cardin. The expansive living room is anchored by two bateau sofas covered in furry Pierre Frey fabric. Two antique leather and metal Savonarola chairs flank the fireplace, and a midcentury brutalist wall sculpture by Marc Weinstein hovers over the mantlepiece. Two postmodern consoles by Kaizo Oto are topped with Edna Ortof’s bright abstract paintings.

“I like bringing different things together, but it’s not easy,” Balbes says. “There’s a comfort to the soul in timelessness.”

With its walls painted in Farrow & Ball’s striking Inchyra Blue, the dining room is the most dramatic space in the house. A vintage starburst Stilnovo chandelier illuminates the circular table, which is set with a sculpture by Richard Mafong and surrounded by midcentury Milo Baughman chairs upholstered in antique Moroccan rug material. Down the hall, the lounge is papered in a silvery abalone, and a 1952 Seguso glass table (originally commissioned for the Hotel Riviera on Venice’s Lido island) sits below the picture window framing a view of the outdoor fountain.

The main bedroom is the epitome of sumptuousness; a majestic Charles Hollis Jones Lucite four-poster bed faces an expansive fireplace, which is flanked by a midcentury Milo Baughman chaise and Poltrona Frau leather sofa and fronted by a 1960s Philip & Kelvin LaVerne bronze coffee table. A sinuous midcentury chandelier by Oscar Torlasco illuminates the main bathroom, whose floor boasts a herringbone pattern of Ann Sacks marble tiles. The serene Duravit tub contrasts with the eye-popping vaulted shower clad in striated marble slabs.

“Balbes clearly senses the philanthropic heritage his new home represents. “I need to do what I can for the community to continue the legacy of this space.””

Moving outdoors, Balbes reconfigured the garden, taking advantage of the surrounding landscape to construct several outdoor rooms. A new rectangular swimming pool was constructed below the kitchen terrace, and the former pool was converted into a koi pond. A rose garden encircles a gurgling lion’s-head fountain, set not far from a female bronze holding a glass sphere, called The Source. Designed by Frederick Hart, famous for his sculptures at the Washington National Cathedral, it has long been part of the garden. “It is a very special one,” says Ridley-Tree, who left it behind as a gift to Balbes. “It would seem wrong to move her from that house,” she adds.

It seems everything has come full circle. Shortly after the renovation was complete, Balbes and Davies hosted the Red Feather Ball in their garden to support the United Way, a nonprofit that honored Ridley-Tree with its outstanding philanthropy award years earlier. Balbes clearly senses the philanthropic heritage his new home represents. “I need to do what I can for the community to continue the legacy of this space,” he says. As Ridley-Tree—who deserves the last word—proclaims, “I’m very fond of Xorin because I think he’s a special spirit and very talented. And I hope that he has a long, happy life there.”

See the story in our digital edition

Creature Comforts

Jeffrey Alan Marks adds a California vibe to an English cottage

Jeffrey Alan Marks adds a California vibe to an English cottage

Written by Cathy Whitlock | Photographs by Sam Frost

There is no better way to observe a designer’s aesthetic than with a peek into their own interiors, since these invariably showcase their talents and offer insights into their personal style. While William Shakespeare famously said, “The eyes are the window to your soul,” a home’s décor runs a close second.

Interior designer Jeffrey Alan Marks’s latest home represents his California lifestyle with husband, Greg, 2-year-old daughter James, and a lab named Coalie. Leaving his cliffside Santa Monica residence of 15 years, Marks was drawn to Montecito for its proximity to the Santa Barbara airport, the inimitable Southern California sunlight, and the combination of an English cottage with a mountain view.

The La Jolla native had one primary goal in mind for the home, which was originally built as a summer cottage in 1928: making it a “modern house for today’s living.” That began by taking the structure practically down to the studs and adding extra square footage to accommodate the view of majestic pines while keeping the house’s integrity with its windows and shutters. Marks’s roots and life journeys set the style for the three-bedroom cottage and guest house. “I lived in La Jolla and on the East Coast, and my training was in London, where I went to school. I wanted an English cottage with a modern twist,” he says. “I knew exactly what I wanted and did a lot of shopping for the house in England.”

“I really built the house for our daughter, James—where it’s colorful and family oriented.”

The result is pure Marks—tailored yet informal, sophisticated yet cozy with natural materials, contrasting woods, harmonious colors, and a laidback vibe. Often known for his breezy beach-color palettes, Marks added forest green as an accent to the kitchen he designed with the British firm Plain English. A painting of the Provincetown pier that Greg—an art director, producer, and graphic designer formerly with Saks Fifth Avenue—gave him as a wedding gift suggested the colors in the living room. “I tried to get away from a lot of blue as I didn’t want it to feel like a beach house even though we are close by,” the designer says. Red is used as a “punctuation point,” he explains. “Something I have never dealt with were punches of red, which you see in the chandelier and painting.”

Marks sourced items for the house’s furnishings from his own collections, noting, “I used a lot of my own Waterside and Oceanview collections from Kravet, as well as some of my old faves from Palecek and A. Rudin.” Blue plays a predominant role in the master bedroom and an adjacent nook that’s a favorite reading spot for father-daughter time. The blue-and-white toile in the daughter’s playroom is a nostalgic nod to Marks’s days as a college intern at the venerable London firm of Colefax and Fowler. He hoped “to bring a little bit of that era into my design and really built the house for her, where it’s colorful and family oriented with little pops of color. I am lucky that I got a baby I could decorate for!”

No cottage would be complete without a proper English garden. While the designer worked with Montecito Landscape, he put his personal stamp on the design. “I wanted it to feel like a house in East Hampton”—where the couple also resides part-time—“with the expanse of a lawn, a fire pit and room to run, and a garden that was not too fussy and English.” The space also provides a place for James to display her talents as a budding gardener. “She likes to garden with me,” he says, “and it’s nice to teach her all about vegetables, planting trees and bulbs, and that has made her a little more grounded.”

Introduced to national audiences as one of the stars on Bravo’s highly addictive Million Dollar Decorators, today Marks is one of nation’s most influential designers with projects that range from London and Nantucket to Los Angeles and Newport Beach. The work has landed him on Elle Decor’s A-List and the pages of The Hollywood Reporter and Architectural Digest, to name a few. He continues to make his mark with lines from The Shade Store and a Point Dume collection with Progress Lighting, and in 2013 the multifaceted designer also added author to his resume with the publication of The Meaning of Home (Rizzoli New York).

The new residence is one of his proudest achievements. “For me it was all about the mix and making it eclectic.” which he accomplished, for example, by pairing a woven rope table with a room of antiques. “During the first seven years with a child, you want to hunker down for a while,” he says. “I wanted the house to feel grounded and substantial—like we have been here for a long time.”

See the story in our digital edition

Perfect Vision

A blissed-out young family finds domestic nirvana in the form of a reimagined 1950s ranch house infused with SOULFUL style

Portrait by Sam Frost

A blissed-out young family finds domestic nirvana in the form of a reimagined 1950s ranch house infused with SOULFUL style

Written by Christine Lennon | Photography by Mellon Studio

The sound of Jessie De Lowe’s voice comes through the speaker of your phone as soothing as an ocean breeze.

In an installment of Manifestation Monday, which she records for her many Instagram followers, she looks directly into the camera, wearing a pale green dress with her long blonde hair in braids, and shares her wisdom. Jessie, who is a “manifestation advisor” with a background in art therapy, talks about reframing and redirecting your attitude to make room for a more abundant life. She calls it “creative destruction,” and to illustrate her point, she describes the four-bedroom Montecito ranch house—with ocean and canyon views—that she and her husband, Proper Hotel and The Kor Group Co-Founder Brian De Lowe, recently renovated along with Tamara Kaye-Honey of House of Honey interiors.

Brian stands behind the marble-top bar while Jessie sits on a Saffron + Poe braided stool. A Hudson Valley Lighting pendant hangs above.

“It can be messy. It can feel worse in the beginning,” Jessie says. “In breaking down the walls and opening up the ceiling, you’re taking a leap of faith that you’ll make the space to create your vision. You don’t know what you’ll find there. It can be chaotic. But you have to trust that what you’re building is better than what you’re leaving behind.” Sometimes you’ve got to take a risk, she adds, and take life down to the studs in order to make your dreams come true. And you should expect some chaos before peace arrives.

The great room leads to the bar, where Portola Paint’s Costes—a muted terra-cotta color—sets the tone for a vintage love seat.

Listening to Jessie and Brian, who are devoted young parents of two girls under 5, share the details of their seamless move from Santa Monica to Montecito is enough to make manifestation naysayers think twice. They believe that they willed their house—which Kaye-Honey describes as “Mallorca meets Montecito, charming, chic, welcoming, and open-minded”—into existence.

In the primary bedroom, a playful mix of muted hues and rich textures takes form in an Anthropologie bed frame, Lulu and Georgia swivel chairs, Armadillo’s Malawi rug, a vintage mirror from the Round Top Antiques Fair in Texas, linen sheets by Cultiver, and One Wednesday Shop throw.

“We were pregnant with our second daughter in early 2020, and we knew we didn’t want to raise our family in Los Angeles,” says Jessie. “We were looking for an easier pace of life, a more community-driven place. Honestly, we were open to anywhere in the world.”

While they were pondering these big life decisions, the world around them ground to a halt. The De Lowes were making regular escapes to Montecito for day trips, beach walks, and picnics to manage the anxiety of living in pandemic lockdown, absorbing as much nature as possible before their return home. “At the end of every day, we never wanted to leave,” says Brian. “It was clear that our dream was closer to home than we thought.”

A fixture by Hudson Valley Lighting is mounted above a custom Kokora Home oval walnut dining nook table, a Brothers of Industry bench, and Rejuvenation chairs.

As it happened, they began their house hunt in a rare stagnant market. “We’d drive up and reach out to brokers about some houses listed online,” says Brian. “It was very clear that we were the only people looking for a house at the time. It was our dream place, the most perfect spot to raise our family, and it didn’t seem like we had any competition.”

“They believe that they willed their house—which Kaye-Honey describes as ‘Mallorca meets Montecito, charming, chic, welcoming, and open-minded’—into existence.”

They moved into a rental, had a baby, settled in, and then the real estate market heated up. The De Lowes, first-time home buyers, knew they should make a move. After touring every house in the community within their budget, one property, a typical 1950s ranch, kept calling them back. And while the house itself was imperfect, the land was “magical, with a huge avocado tree that just keeps on giving,” says Jessie. “It’s kind of wild, very tropical and filled with mature fruit trees. There were chickens roaming around. It was exactly our vibe.”

Concrete Nation’s Valencia free-standing tub and Arc basins—all in the color nude—set the tone in the primary bathroom. Hardware is by Kohler, tiling is by Concrete Collaborative, and mirrors are by Rejuvenation

“The house did not blow us away,” Brian adds. “But we thought, ‘If we did this, and this, and this, and this, and this, it could be our dream house.’”

The De Lowes had a vision they knew they could bring to life, but they needed guidance. They’d long been admirers of Tamara Kaye-Honey’s work and approached the Pasadena- and Montecito-based designer. “We met Tamara for an Aperol spritz at the Miramar Club,” Brian says. “She has such an amazing vision, but she understood that we had ideas and she didn’t steer us away.”

Surrounded by Brothers of Industry cabinets, Riad Zellige tiles, Sun Valley Bronze and Emtek hardware, the Ilve Majestic II range and hood are the focal point of the kitchen, where Jessie is whipping something up in her Our Place Always pan.

Kaye-Honey describes the De Lowes as trusting and an “amazing, positive force.” Brian and Jessie were “open to collaborating and game to be pushed outside of their comfort zone. As a firm, we work holistically to create soulful spaces layered with color, pattern, and texture in ways that feel fresh and unexpected, all while remaining invitingly livable and timeless,” she adds. “We take it seriously—but always with a wink and a smile.” The De Lowes were ideal clients for the HOH aesthetic, which is sophisticated but playful, chic but still comfortable.

The family relaxes on the deck's Neighbor patio furniture, beneath a Santa Barbara Designs umbrella.

Brian acted as the project’s general contractor with a local builder, drawing on his experience developing properties for The Kor Group, building Proper Hotels, and working closely with uber designer Kelly Wearstler on those. “[With Kelly,] we really want [the hotels] to feel residential and comfortable, and then to have these special wow moments,” Brian says. “Jessie and I approached this home in the same way. This is a family home first and foremost, and it feels really comfortable, definitely not too modern or fancy.”

A Jenni Kayne dining table and chairs are complemented by a Z2 Blond Paper Cover pendant from Global Lighting and the Colina credenza by Kelly Wearstler.

A few important focal pieces deliver the “wows” Brian mentions: the blue-gray Ilve stove in the kitchen, custom-designed Architectural Iron Works doors that create a flow between the main living room and the outdoor lounging and entertaining spaces, a Concrete Nation tub in the spa-like primary bathroom, and unique marble slabs. New pieces, like the Jenni Kayne dining table and a custom dresser in the primary bedroom, are balanced by one-of-a-kind antiques and rugs that the couple picked up at the Round Top Antiques Fair in Texas.

“They wanted a home that had rustic sophistication and communal vibes that wasn’t overly designed and loud,” says Kaye-Honey.

And while the De Lowes admit that taking on a full-scale renovation project with tiny children at home and two busy careers isn’t exactly a cinch, knowing that they were fulfilling their dreams helped. “It can be stressful,” says Jessie during her Instagram installment, “but what calms you down and translates anxiety to excitement is visualizing what the dream will feel like and look like. Mentally rehearsing walking through the house helped me get clear about the decisions we were making. Staying in your comfort zone, although it might feel good in the moment, keeps you stuck.”

And now that the vision is a reality, they don’t take their fortune for granted. “Every day, at least once a day, Brian and I say how grateful we are to live here,” she says.

See the story in our digital edition

A Monument to Madame

In LOTUSLAND Ganna Walska created a world-renowned horticultural treasure

In LOTUSLAND Ganna Walska created a world-renowned horticultural treasure

Text and images excerpted from Lotusland: Eccentric Garden Paradise (Rizzoli New York) | Photography by Lisa Romerein

How do you describe Lotusland? Exquisite garden, conservation center, the botanical expression of an exuberant and idiosyncratic personality…it is all that and more. For almost thirty years visitors have had the privilege of exploring this natural sanctuary, wandering the paths that showcase the incredible variety of the collection, from the majestic palms and ancient dragon trees to the prickly array of cacti and the shadowy elegance of the Japanese Garden. Lotusland changes with the seasons and has evolved gradually with the decades, but the allure of this incredible estate never lessens. It remains a tribute to the extraordinary woman who brought the place to life. Joan Tapper

Ganna Walska Lotusland, a thirty-seven-acre oasis located in Montecito, California, is considered to be among the most significant botanic gardens in the world. Home to more than 3,400 types of plants, including at least 35,000 specimens, it is recognized not just for the breadth and diversity of its collections, but for the extraordinary design sensibility informing the many one-of-a-kind individual gardens that comprise its cohesive, harmonious, magical whole.

Madame Walska’s maximalist ethos is part of what makes Lotusland so unique.

As delightfully pleasing as its aesthetic and sensory qualities are, Lotusland is also an important center for plant research and conservation.

Lotusland opened its gates to the public in 1993, nine years after the death of the estate’s owner Ganna Walska, referred to by all as “Madame.” She was an adventurous, inquisitive, and charismatic spiritual seeker who lived a life of legend. Born Hanna Puacz in Brest-Litvosk, Poland, in 1887, she eloped with a Russian baron in 1907 at age twenty. After changing her name in 1914, Madame Walska, as she was now known, moved to New York and in the ensuing years shuttled between New York and Paris, performing as an opera singer and marrying five more times after the baron’s death.

Already a student of yoga, astrology, meditation, telepathy, numerology, Christian Science, and Rosicrucianism, around 1933 Madame Walska embarked on her search for the “great purpose” of her life, studying hypnotism and Indian philosophies. Her studies led her to meet Theos Bernard, a similarly charismatic individual and yogi who was one of the earliest, and most famous, proponents of Hatha yoga in the West.

Unlike a traditional museum, Lotusland’s living collections are ever changing and ever evolving.

Bernard became Walska’s final husband in 1942. The previous year, Walska purchased the property then known as Cuesta Linda, which they intended to serve as a retreat for Tibetan lamas: together, they renamed it Tibetland. Alas, World War II scuttled their plans to bring the lamas to America, and in 1946 Walska and Bernard divorced. Madame promptly renamed the estate Lotusland after the sacred aquatic plant that flourished there.

Immediately after acquiring the land in 1941, Madame Walska hired the renowned landscape architect Lockwood de Forest, Jr. to renovate the orchards and create a number of individual garden spaces on the property. Following de Forest’s deployment to World War II in 1943, Ralph Stevens, son of the property’s garden original owners and then the Santa Barbara Parks Superintendent came on board, and over the next decade he, alongside Madame Walska, developed many of Lotusland’s iconic landscape features.

Over the course of forty-plus years, the once-native land that had been home to a commercial nursery for its initial use was transformed into a garden paradise full of staggering natural wonders. Madame Walska led by instinct and with a passion for the best (and most!) collectable plants on the planet. She sought out, consulted, and engaged the best experts in their fields to help shape and realize her vision for Lotusland, but it was always her distinctive vision. Her maximalist ethos, typified by signature gestures such as the profuse grouping of single specimens, the assemblage of massive varieties of plant families, and the deployment of extravagant, dramatic gestures, is part of what makes Lotusland so unique among botanic gardens throughout the world. Eye-catching and unorthodox garden adornments, such as large chunks of colored glass, gems and minerals, and giant clam shells, appear in the landscape and contribute to the estate’s visual excitement.

And yet, unlike a traditional museum with static installations, Lotusland’s living collections are ever changing and ever evolving. Plants mature, plants die. Room has to be made for exciting and scientifically more important new additions. Since the late 1990s, the garden’s living collections have grown significantly, and several gardens have been restored and reimagined to support their function in this now public garden. Today, the goal of its stewards is to preserve and enhance the historic estate and gardens of Madame Ganna Walska, and to develop conservation and sustainable horticulture programs that educate and inspire, while advancing global understanding and appreciation of plants and environmental responsibility.

See the story in our digital edition

Escape Artists

Interior designer John De Bastiani refreshes a Montecito residence for a creative couple’s weekend retreat

Interior designer John De Bastiani refreshes a Montecito residence for a creative couple’s weekend retreat

Written by Jennifer Blaise Kramer | Photographs by Joe Schmelzer

When an L.A. couple—one of them an artist—looked for a weekend respite, they found it in a single-level 1957 ranch home in Sycamore Canyon. It had been previously owned by a noted landscape designer who curated the grounds into a classic Santa Barbara oasis. In an effort to spruce up the interiors, the new owners enlisted designer John De Bastiani (who had helped the empty nesters with their primary residence), kicking things off with the one thing a painter wants most—color.

“We wanted that modern farmhouse feel without the cliché.”

“They love rich colors,” says De Bastiani of the owners. He focused on combinations of blues, greens, and clays, explaining, “We wanted to warm up the house for a cozy, wonderful retreat.” Jewel tones of green and blue were woven throughout, bringing in earthy shades from the garden but in more saturated hues. Out front he painted the shutters and trim an olive green to contrast with the white board-and-batten siding. Inside, the primary bedroom is decorated in watery blue, and the designer added strapping on the walls and closet doors to lend texture against the existing ceilings. Using the same shade on all surfaces created a cocoonlike coziness, heightened by homeowners’ choice of replicating their main home’s familiar four-poster bed and pairing it with a fluffy Moroccan rug.

A leafy green color now graces the kitchen, where De Bastiani built a secondary wall of cabinetry, complete with brass library lighting. “We wanted that modern farmhouse feel without the cliché. Here the green pivots and elevates,” he says, adding, “we wanted that pop and must have tried 20 different shades—this was a little bright but not too faddy. It’s classic.”

The green also nods to the lush gardens visible from the kitchen’s convenient serving window, which makes passing cocktails from inside a breeze. Friends can grab a drink and wander over to the firepit or outdoor lounge, which is furnished with low-slung wooden sofas from The Well. Pebble gravel underfoot is accented by low-water plants and tall oak trees, from which De Bastiani hung vintage metal lanterns to create a nighttime glow.

“It was all very romantic already but a little overgrown,” he says. “The owners wanted cleaner lines, so we simplified in a wonderful Montecito way.”

“The house had beautiful bones in place, so it was a delicate balance to add contemporary things.”

In streamlining the layout inside and out, the designer arranged special places to entertain. For parties, the couple either hosts intimate dinners in the garden’s new greenhouse room—also furnished from The Well and wired with vintage globe pendants—or holds them in the dining room, where a custom table is positioned close to bifold doors, “which are always open so you feel like you’re in the backyard.”

Natural light spills in from outside through the original front door, adding to the California ranch-style character. “The house had beautiful bones in place, from the floors to the steel casement windows throughout, which people request today, so it was a delicate balance to add contemporary things,” De Bastiani says. In the living room, for example, he chose muted tones from the same palette of greens, blues, and rusts to create an elegant backdrop for the antique pieces that mingle with contemporary furnishings and art—mostly the homeowner’s, of course.

“It’s an artist’s cottage,” De Bastiani says. “And we made it into a jewel box.”

See the story in our digital edition

Shelton Style

The architect creates his signature works with dazzling craftsmanship, flair, and imagination

The Architect creates his signature works with dazzling craftsmanship, flair, and imagination

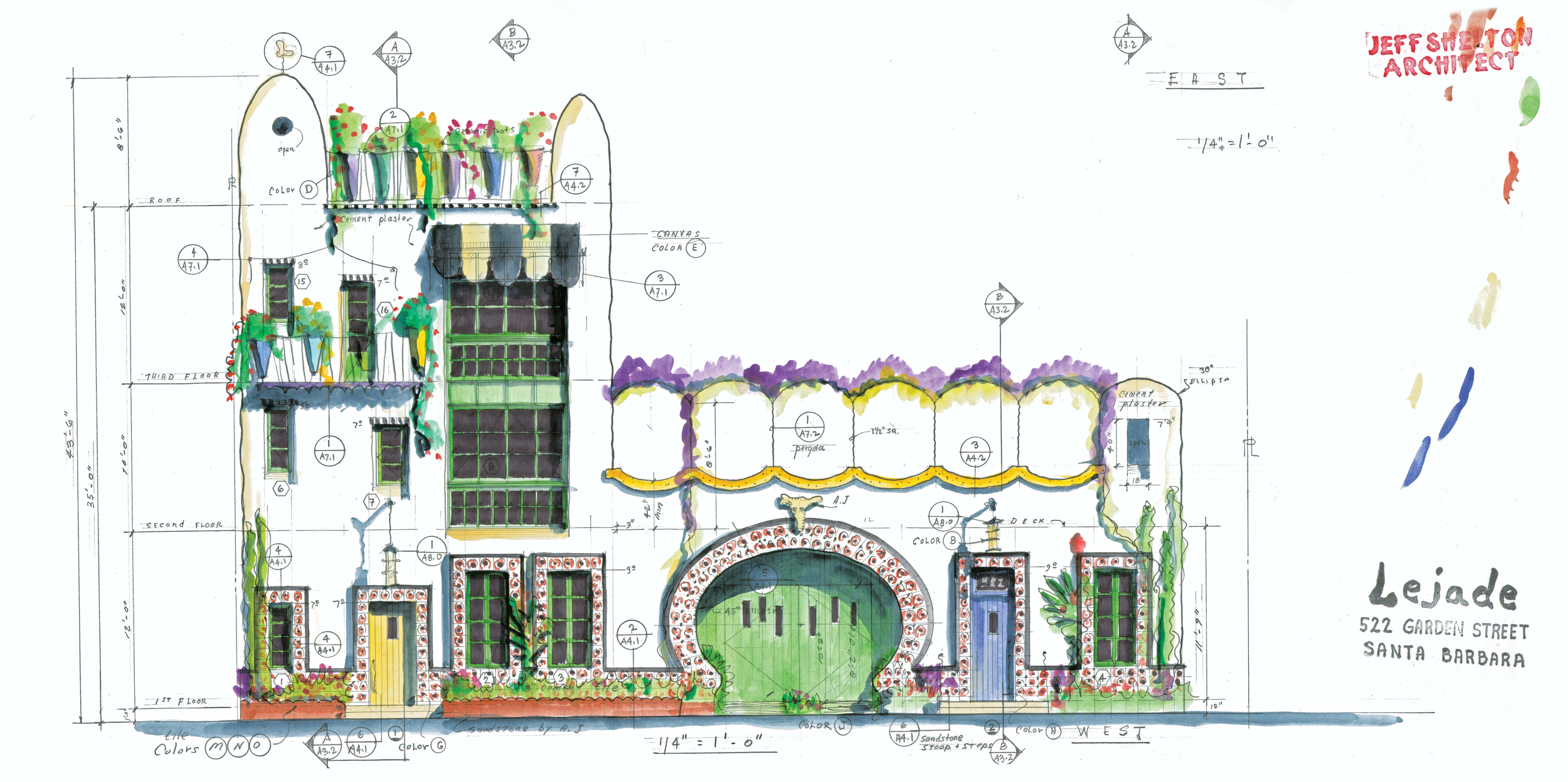

Text and images excerpted from The Fig District: Some Buildings in Downtown Santa Barbara (Fig Press) by Jeff Shelton with photography by Jason Rick

The Fig District is a figment. There is no Fig District. That is, unless your office is on Fig Avenue, and you have been lucky enough to have designed eight buildings within six blocks of your drawing desk.

A city would never name a district after this glorified alley. Fig Ave is an endearingly derelict one-block street in downtown Santa Barbara, behind a handful of State Street’s bars and restaurants. By day, beer kegs are unloaded from delivery trucks, denting the asphalt with friendly smiles and making sounds like hammers hitting an anvil, and at night, intoxicated revelers regurgitate maps on the sidewalk after having had too much to drink.

My office has been on “Fig” for twenty-three years. For fifteen of those years, my brother David’s ironwork shop was one hundred steps from my office door, in the old Hendry Brother’s Steel Shop on the corner. One hundred steps in another direction is the James Joyce pub, where we made our conference table for afternoon meetings. Having designed two buildings only a Frisbee throw from the office, and six more within six blocks, we at some point began referring to this zone as “The Fig District.” Buildings I design within this district tend to get an extraordinary amount of my attention, as daily walks to the coffee shop inevitably lead to job site visits.

The buildings in this zone are architecturally related as most of them sit within Santa Barbara’s Historic Landmarks District, or “El Pueblo Viejo,” as the City refers to it. This design district was created after an earthquake in 1925 destroyed many buildings in Santa Barbara, and it requires buildings to conform in some odd way to design standards based on the historic influences of Andalucia and Southern Spain. Essentially, the buildings need to incorporate plaster, ceramic tile, terra cotta tile, and ironwork, using building proportions that mimic stone or adobe construction. Design Review Committees carefully scrutinize projects in this area to make sure they’re sympathetic to the City’s strict guidelines.

I designed each building to maintain an inherent pedestrian orientation and to be sensitive to the community as a whole.

When I moved back to Santa Barbara, I hadn’t worked with plaster on any projects in my early career as an architect. I had worked mostly with steel, glass and concrete block. To begin to understand what this “Spanish thing” was about, I found books with photos of cities and buildings in Spain, and realized the beauty and opportunity that existed in the malleability of plaster.

In 2000, I started designing the Pistachio House, which was the first of my eight projects in The Fig District. Since these buildings are downtown, I designed each to maintain an inherent pedestrian orientation, to react to its neighboring structures and to be sensitive to the community as a whole. Seven of these projects were built by Dan Upton and his crew of talented builders, and my brother, sculptor/ metalworker David Shelton, designed and brought the ambitious ironwork to life on all eight.

All of the people who have worked on the Fig District projects have grown to understand that it is the building, not the architect, that begins to make the design choices.

The same freewheeling, independent band of local artisans and craftspeople have added an extra layer of life to all of these buildings and at each location, you’ll find their names listed on ceramic tile plaques. Though the idea of working with a guild is from another time, we have somehow found ourselves in the middle of one, full of people with similar goals and dedication to their craft. We use the term loosely, perhaps romantically, throwing out any cumbersome archaic politics but keeping the interesting and productive ideas of a guild.

A stroke of good fortune for the buildings in the Fig District, as well as the other buildings I’ve designed, is that we have somehow been united with great clients willing to jump into our world and let a project organically grow from logic and delight. There is an uncommon amount of trust and faith required in this process and for a time, the Guild will be part of the client’s life. One client once described the job site experience this way: “First there is the rough grading, and then the Merry Band of Artisans shows up.” Our job sites are always joyful, even on the bad days.

Our intention is always to give life to the street and to create a building that invites and brings delight to the pedestrian and the community. The construction of a building should be an enjoyable event.

When prospective clients come into the office, I first try to scare them off. Some leave right away, perhaps in astonishment, wondering how anyone would want to jump onto a seemingly unruly bus rambling down a narrow mountain road with the seats already full of the Merry Band of Artisans and all of their family members, only to be asked to close their eyes and have faith that the journey and the outcome will be a success.

Over the years, new workers, artists and craftspeople filter into our odd building process, while others move on or retire. One thing is clear; all of the people who have worked on the Fig District projects have grown to understand that as each building emerges out of the ground, it is the building, not necessarily the architect, that begins to make the design choices and we all need to show up and listen to it every day. Sometimes the stars line up and sometimes we need to draw a curvy line to get them to align, then squint and pretend that they’re lined up exactly how we want them to be. Whatever the means, creating a building requires the imagination, perseverance and cooperation of a lot of people who want to go in a similar direction, who are not confined by restraints and norms that seem to stifle thought and keep us from taking big breaths of life.

Buildings are designed with pencils and pens on vellum and tracing paper, and the designs reflect the relationship of a hand-drawn line interpreted by hands in the field. The people building these buildings appreciate the care that goes into the plans and so in turn put in the same amount of thought when they show up each morning to work. Everyone has the desire for beauty and delight, and that sometimes takes a fight and sacrifice to achieve.

Meanwhile, I fiddle with my pencil as I wait for the next Fig District client to knock at my door.

See the story in our digital magazine

Chicana Cultura

An urban tour of the Eastside and Milpas corridor—taste, see, and learn what makes this side of the neighborhood and its people so special

An urban tour of the Eastside and Milpas corridor—taste, see, and learn what makes this side of the neighborhood and its people so special

Written by Michael Montenegro | Photography by Sara Prince and Dewey Nicks

CRUISING

George Trujillo’s family business—his barber shop—was established in 1929. It’s like going down memory lane, with the original vintage barber sign and black-and-white checkered floor. Brothers Efrem Reynozo (in the 1957 Chevrolet Bel Air convertible in Inca Silver) and Rene Perez (in the 1958 Chevrolet Impala in Blue Magic) cruise the backside of Ortega Park. If you are lucky, you could soon take a tour of the American Riviera in style too—Reynozo will be launching a vintage-car tour service in 2022.

TASTE CALLE MILPAS

The iconic La Super-Rica Taqueria that Julia Child called one of her favorites. Owner Isidoro Gonzalez’s tacos and tamales still draw crowds lining up around the block, and he only takes cash. Do as locals do to get the morning started with pan dulce or a breakfast burrito at La Tapatia Bakery. Craving seafood and Mexican food? Look no further than Cesar’s Place; the michelada is a must-try too.

FIESTA

It’s not a party without a piñata. The tradition has Mesoamerican Native roots and has been practiced in our community for over a century. Find these colorful favors—which were originally made of clay—at local stores or visit Chapala Market (shown here), one of the best-stocked and most-frequented tiendas on Milpas.

Ortega Park is the heart of Santa Barbara. The vibrant murals tell the stories that represent our diverse community. If only this piece of land could talk—its memories would span from being a salt marsh to a town dump to the creation of the historic park in the 1920s. Decades of celebrations have taken place here, like Cinco de Mayo festivals with lowriders, quinceañeras, and block parties. It’s the people—the children, parents, and elders from the neighborhood over the generations—that make the park special. Ortega Park was intersectional because of the multiculturalism of African, Italian, and Irish people, alongside those of Mexican heritage. Generations migrated here to pursue the American dream for a better future for their children.

MENTORS

Superior Brake and Alignment owner Bob Seagoe services classic cars and gives back to local youth by offering mechanics apprenticeships, since many of these technical classes have been cut from local high school budgets; El Potrillo Western Wear carries Mexico’s finest boots and clothing and offers discounts for local charity and school fundraisers; Bobby Bisquera, aka Mexipino, in his 1961 Chevy Impala convertible; Efrem Reynozo; crafts from Mujeres Market; Danny Trejo, president of Nite Life, the longest running automobile/lowrider car club in Santa Barbara.

Think of locals dancing to cumbia and decompressing to Mexican ranchera music.

NIGHT LIFE

La Pachanga Night Club unfortunately is not active anymore, but it once was the place to be: It was loud and carnival-like and felt like a hometown dive bar or cantina that would encapsulate you somewhere in the Southwest or Mexico. It was a place where English was spoken as a second language, with a Latin accent.

Raze Up hits the streets; Ruben Perez in a 1957 Chevy Impala in Blue Magic; in the summer of ’75, neighborhood children immortalized themselves in concrete during the completion of Ortega Park; Trejo’s 1952 Chevy Suburban; Michael Montenegro, writer and filmmaker (@ChicanoCultureSB). Jorge Salgado, owner of the Barber Shop, and his 1950 Mercury; Cindy Falcon, a legendary Chumash Chicana, was the president of Ladies United, an all-women lowrider/automobile club during the 1970s; Augie Trejo in his 1950 Chevrolet Deluxe; Art Perez’s 1939 Chevrolet coupe.

THE FUTURE

Beauty with resilience runs in the Jaimes family: Valerie, younger sisters Lilyanna and Alicia, and mother Charlotte. Valerie, a community organizer and activist, was born and raised in Santa Barbara, is an alumna of Santa Barbara High School, and recently graduated from the University of San Diego—the first member of her family to graduate from college—with a bachelor’s degree in ethnic studies and sociology. “Higher education has empowered me to be who I am,” she says. “My future is to be an educator and empower my community to be who they want to be, whether they want to learn a trade, be an artist, or explore outer space.” Valerie is currently residing on Kumeyaay indigenous land and working with the Chicano Park Museum and Cultural Center in San Diego.

See the story in our digital magazine

On Kyle’s Pond

A Native New Yorker finds Art in Nature

A Native New Yorker Finds Art in Nature

Kyle DeWoody afloat in the natural swimming pond at her Central Coast ranch.

Written by L.D. Porter | Photographs by Sam Frost

She’s been at the center of the art world for most of her life. But for the past five years, Kyle DeWoody has spent much of her time in rural Ventura County, navigating a Kubota utility vehicle over uneven terrain to see how her avocado, banana, and mango trees are faring. This may shock those familiar with her undeniably glamorous image, featured in Vogue, Vanity Fair, and W magazine, and on countless art blogs. But close companions know it’s simply another interesting curve in the New York native’s fascinating life trajectory.

Let’s start with genetics. Her father, James DeWoody, is a renowned artist whose work resides in many private and public collections, including New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her mother, Beth Rudin DeWoody, is a philanthropist, arts patron, and curator, known for championing overlooked artists. Given that pedigree, DeWoody says, “I had no chance of escaping the art world.”

In fact, the art world came to her. “It was obviously an incredible treat to grow up around not only amazing art but amazing artists,” she says, adding, “most of my parents’ close friends were artists or curators.” Art history was her chosen topic at Washington University in St. Louis, and her real-world experience was honed by stints at the Whitney Museum and Creative Time, a nonprofit institution that commissions public art projects.

She co-founded the e-commerce site Grey Area in 2011, with unique editions of art, jewelry, and objets; it ultimately expanded to include pop-up installations combining art exhibitions with art-related merchandise in tony locales like the Hamptons, Miami, and Los Angeles. Soon DeWoody became a go-to advisor for boutique hotels and brands seeking to create special environments with art. In other words, she’s a major influencer and tastemaker.

But success can exact a toll, and for DeWoody that amounted to a series of chronic health issues that demanded attention. The path to healing pointed to Los Angeles, where her brother Carlton had decamped a couple years earlier and her mother had established a pied-à-terre with husband Firooz Zahedi, a noted photographer. (L.A.’s stellar art scene likely sealed the deal.) DeWoody embarked on a program of self-care with health-care practitioners and holistic treatments including integrative stretching (a form of fascial release to repair structural and physiological issues) and dietary changes to eliminate inflammatory foods. The healing process fueled her desire to connect with the land in a direct way, a desire that was fulfilled when she discovered a sprawling ranch—formerly a walnut farm—in a lush valley between Carpinteria and Ojai.

From the moment she walked onto the property, DeWoody could sense that a natural pond would fit perfectly in the landscape. Used throughout Europe, eco-swimming pools eschew chemicals, using plants to filter the water. Although the concept is just starting to catch on stateside, DeWoody is a quintessential early adopter. She designed the pond’s configuration, and David Cameron helped put the final touches on the landscaping. “It’s an evolving technology and not for everyone,” she admits, “but it feels so good, and it’s incredible to swim next to lotuses and grasses.”

The pond is in plain view of a tiny ranch house DeWoody has lovingly refurbished with wood salvaged from fallen walnut trees on-site, the unfortunate victims of California’s now-pervasive drought. Hence the lovely walnut countertops, ceiling-beam edging, and custom furniture gracing her small abode, all achieved with the assistance of talented designer Case Fleher. As of now, roughly 5 of the ranch’s 65 acres are landscaped; the remaining acreage has been cleared for fire protection (thanks to seasoned caretaker Paco Alexander) but otherwise left to grow wild.

Of course, even in this bucolic setting, art and activism are never far from DeWoody’s mind. Before COVID, she curated projects like “My Kid Could Do That,” a recurring fund-raiser featuring childhood artwork of prominent artists (think Ed Ruscha and Catherine Opie) to provide free arts programming for children, and supported fund-raising efforts for L.A.-based Habits of Waste, a nonprofit whose goal is to activate simple behavioral changes to reap a powerful impact, like banning single-use straws and cutlery. “All the things we take for granted are no longer a given,” DeWoody notes: “how we treat each other, how we feed ourselves, how we ensure a future for our children. Everything needs to be fought for in a certain way.”

Along with her romantic partner Samuel Camburn, a screenwriter and actor, DeWoody recently hosted a group of artists affiliated with the Ojai Institute, an initiative of Ojai’s Carolyn Glasoe Bailey Foundation, gathered by the foundation’s executive director, Frederick Janka. Under spreading olive trees, they dined on a magnificent plant-focused feast prepared by chef Loria Stern. Ezra Woods of L.A.’s Pretend Plants & Flowers and artist Samantha Thomas foraged foliage to garnish the lavishly appointed table. Noted ceramist Yassi Mazandi brought along her handmade shot glasses (perfect for tequila quaffing), and artist Ry Rocklen added his Pixie ceramic sculptures.

DeWoody credits her involvement with the land as a key to her improved physical well-being. It’s also no surprise that the prospect of a pristine landscape would naturally whet her appetite for curating art installations, and that’s exactly what’s up next. The rest of the beautiful felled walnut wood will be distributed to artists to create pieces for a future art installation. The art world is indeed DeWoody’s world.

“All the things we take for granted are no longer a given: how we treat each other, how we feed ourselves, how we ensure a future for our children. Everything needs to be fought for in a certain way.”

See the story in our digital magazine

Keaton, Au Courant

The star and executive producer of Dopesick shares some thoughts on impactful movies, Santa Barbara, and the importance of the arts

The star and executive producer of DOPESICK shares some thoughts on impactful movies, Santa Barbara, and the importance of the arts

Interview by Roger Durling | Photographs by Dewey Nicks

In 2001 I owned a coffee shop in Summerland, California, and Michael Keaton would frequent it. When he first introduced himself to me, wearing a baseball cap, he simply said his name was Michael. But that voice I’d heard in Mr. Mom and Beetlejuice was easily recognized, and the lips that were accentuated by the mask he wore for his iconic take on Batman instantly gave him away. We struck up a friendship based on our curiosity for movies, and we would have conversations about up-and-coming Mexican filmmakers like Alfonso Cuarón and Alejandro González Iñárritu. Little did we know that he would go on to star in the latter’s Birdman or that the film would mark one of the greatest comebacks in Hollywood history. For two decades Keaton and I have kept in touch. He’s continued to ride this new rewarding artistic phase of his career with challenging work, including starring in and executive producing a Hulu series called Dopesick, which may be his finest performance to date. He’s one of the best actors working today.

Recently, we sat down to converse once again, over lunch at the El Encanto hotel.

Dopesick is an amazing series.

I just watched myself, and this is the first thing I’ve watched of mine in many years; I don’t like to watch myself. I lost a nephew to fentanyl and heroin. So I wanted to watch to make sure we did it right.

I don’t remember a TV series with so many flashbacks. Did you shoot it chronologically?

I was already committed to doing another film in the UK, and I had to be there by a certain time. And I was in a crunch in terms of when I could do Dopesick. Therefore there was almost no shooting in any chronological time for me. At some point I just gave in to the thing.

Did the things that you learned from shooting Clean and Sober help you with this?

It was a huge advantage. And then I thought to myself, Wait, am I just being lazy? And that’s a distinct possibility. But what I learned from the research during that movie helped enormously.

Why don’t you like seeing yourself in movies?

I don’t know. I’m self-critical, and I’m not really that interested. I want to move on to the next thing.

Keaton keeps under the radar locally—enjoying foggy beaches in the winter and time with his horses.

Is there one movie that you’re particularly proud of?

Well, because Birdman and Beetlejuice are so truly original—and I don’t throw the word “art” around a lot—I’m proud of those two for sure. I always like to give art people—actors, directors, writers, painters, anybody in the art world—a ton of points for courage, for risking, for being willing to fail and fall. I would, off the top of my head, say those two for those reasons. Multiplicity is really underrated because of the degree of difficulty. I’m sure there are others. But to make Multiplicity now would be technologically much easier. It was so much fun to try to figure out and do.

After Birdman, you went on to do Spotlight, The Founder, The Trial of the Chicago 7, Worth, and now Dopesick. And they’re all questioning and talking about American issues, social-justice issues. Is that a conscious thing?

I grew up in a house where my parents would discuss things. Sometimes not even on an intellectual level. There was just discussion. My dad was involved in local politics. I was excited when I became 18 because that was the first year I could vote. That was huge. So it’s always been there, and I’m always watching news and reading newspapers, and I stayed conscious. There were years where I was less involved, but I’m probably more a product of my generation than anything else.

“I’m extremely fortunate, honestly, to have a job that I really like, that might possibly have an impact on people.”

Being in a movie like Spotlight, you put a face to abuse by priests.

I was also an altar boy and a devout Catholic for a long time.

And by being in Dopesick, you put a face to addiction, to OxyContin.

Yep. And Clean and Sober.

And shedding light on 9/11 in Worth.

And what I did in My Life, I always thought it pretty good. It may not be brilliant, but if this all falls apart tomorrow and I don’t ever get hired again, I’ll have something in the world that may help somebody. I’m extremely fortunate, honestly, to have a job that I really like, that might possibly have an impact on people.

“I always like to give art people—actors, directors, writers, painters, anybody in the art world—a ton of points for courage, for risking, for being willing to fail and fall.” Jacket courtesy of Brunello Cucinelli, Rosewood Miramar.

This career renaissance that you’re in right now, how do you feel about it?

It’s fun! And I do get how it’s called a renaissance. And I honestly did get how people referred to Birdman as a comeback. I’m OK with it. To me, it’s just me going to work. I’m just doing what I’ve really always done. Have I turned up the volume a little? Yeah, for sure. And I think some of it is because I like it more than I have for a long time.

You were always popular, and people adore your doing blockbusters and popular comedies, but after Birdman, now you’re like an American Laurence Olivier.

Hold on now.

You’re like this very serious actor.

That’s nice, and I think at some point, if I step back and look at things, I wouldn’t be shocked if people say, “Hey, Mike, thank you, and with all due respect, you’re a serious dude. Now do us a favor, lighten the fuck up for a while.”

I don’t think you’re going to have that problem.

Well, it’s just so much fun to do comedy. I miss it so much. And when I work on it, I’m really, really diligent about it. I admire it so much when I see it done well.

“Have I turned up the volume a little? Yeah, for sure. And I think some of it is because I like it more than I have for a long time.”

When did you first come to Santa Barbara?

The very first time I came to Santa Barbara was in the late ’70s. Me and a couple of pals drove my ’63 VW Bug up here, and we slept on the beach. It was cool. And remember how horsey it was then? But horsey in the coolest way. There would be horses walking along the streets, right through town.

Even 20 years ago when I met you.

One of the most impressive things I find up here is the Montecito trail system. I’m amazed that they continue to keep it going. When I first came here, I didn’t have any money. I may have had $280 when I came to California. So my brother loaned me some money, and I bought a car for $700 and came up here. I thought, What a beautiful place. And I remember the light, and I went, Wow, this light is really special. And I thought if ever I could afford a second place, maybe this would be a fun place. I’ve had a few places here and there and kind of kept it under the radar.

Keaton discovered Santa Barbara in the late ’70s by driving up with some pals and sleeping on the beach. Now he enjoys the easiness of strolling the Summerland streets.1969 Barracuda convertible courtesy of Jill Johnson/Loveworn.

What does Santa Barbara represent to you? In your interviews you mention Montana and keep Santa Barbara out. Is it intentional?

I’m a California fan, actually. First of all, physically, it’s really pleasant here in Santa Barbara, and it’s a great place to just get out for a minute. I love the beach in the winter, and there’s not many people around on the beach in the winter. I love that this morning the fog was so stunningly beautiful. The changes in the climate are great. And then once I could move my horses here, it became even better.

And people leave you alone.

Yeah, the people are totally cool. But since I’ve been small, I’ve always been very aware and sensitive to my physical surroundings—like scale and light and space. I think there’s just a ton of really interesting people here: T.C. Boyle and others.

You know what I find as I get older? I get more excited about true creativity or art. Thomas McGuane is a good friend of mine. I was just reading one of his pieces in The New Yorker. I read it, and I went, Man, there’s a couple of phrases.… Like when you read something great, you have to set the book down and go, I just have to think about what I just read. Or when you see a true painter or an original painting. Don’t you find that the longer you live, you actually get more excited about that? And I don’t know if that’s a question of me going, I don’t have that much time, I’ve got to savor all of this. I don’t know what it is, but I get excited about anything creative or artistic or anything having to do with art. It’s thinking, Am I ever going to really get them? To really get it?